This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

Young Writers Need Models

Young writers need models. Early in my apprenticeship my predecessors fed me greatly. Still, I was also very eager to find work by young black male contemporaries, which I thought might be more relatable. When I discovered that Richard Wright published Native son around 32, James Baldwin Go Tell it On the Mountain around 29, James Alan McPherson Hue and Cry around 25, then winning the Pulitzer Prize around 35, and Jean Toomer Cane around 29, I thought, surely, there had to be a living young black male fiction writer whom I could turn to as a model. After a dedicated search, I found none. There were some young black male writers producing contemporary works of fiction, but their work seemed determined only to entertain. I was looking for something more, a deeper, richer perspective. Later, after a more thorough and committed search, I did find one young black male writer who seemed to have a deep respect for the art form and the urgent need to try to get life right on the page. Where were the rest?

Young writers need models. Early in my apprenticeship my predecessors fed me greatly. Still, I was also very eager to find work by young black male contemporaries, which I thought might be more relatable. When I discovered that Richard Wright published Native son around 32, James Baldwin Go Tell it On the Mountain around 29, James Alan McPherson Hue and Cry around 25, then winning the Pulitzer Prize around 35, and Jean Toomer Cane around 29, I thought, surely, there had to be a living young black male fiction writer whom I could turn to as a model. After a dedicated search, I found none. There were some young black male writers producing contemporary works of fiction, but their work seemed determined only to entertain. I was looking for something more, a deeper, richer perspective. Later, after a more thorough and committed search, I did find one young black male writer who seemed to have a deep respect for the art form and the urgent need to try to get life right on the page. Where were the rest?

Given post Civil Rights era progress and the fact that there were many young black male poets, I wondered, “Why is there such a lack of young black male literary fiction writers?” The decline, beginning in the early 1980s, is striking. For a time, I attributed the shortage to the way of the publishing industry, specifically the large New York publishing houses. I reasoned that during the Harlem Renaissance and the following decades the gatekeepers of the publishing world were more actively looking for more young black male voices. The socio-political climate of the times raised the demand for their perspective. Big publishing houses, and those connected to them, look for what they think is going to sell well. Writers who appear not to represent the mainstream benefit from spikes of perceived popular interest. Yet, the trends of big publishing are not responsible for the halting of young black male literary voices.

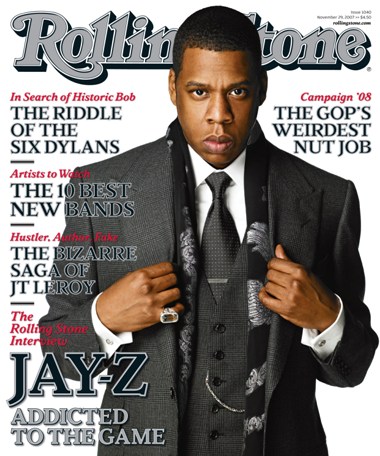

I found the answer after giving a talk at Northern Illinois University. My audience was a group of young men who were in the university’s “Chance Program.” In an attempt to stress the importance of literacy, I created audio snippets of rap songs that I knew contained direct references to books. For example in the song “Some How, Some Way” Jay-Z says, “Look man, a tree grows in Brooklyn,” which is a direct reference to Betty Smith’s successful 1943 novel by the same name. Talib Kweli and Mos Def’s “Thieves in the Night” pays homage to Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye by creating an entire song inspired by the last paragraphs of the novel. Nas’s “2nd Childhood”, is arguably a reference to a paragraph in Black Boy where Richard Wright explains his existence in Chicago being like “a second childhood.” Using more examples like these, I explained to the young men that the best rappers must be highly literate and the mentioning of books in their lyrics was an overstatement of that fact. After the presentation, I continued to think about literacy and Hip-Hop artists. I thought about the songs that I loved, those songs that were vivid and real, which sometimes took me to a distant place, and at other times, a place of familiarity. The best Hip-Hop songs, those that told stories, excited me as great scenes from books did. I came to the conclusion that my favorite MCs were the young black writers for whom I had been searching.

I found the answer after giving a talk at Northern Illinois University. My audience was a group of young men who were in the university’s “Chance Program.” In an attempt to stress the importance of literacy, I created audio snippets of rap songs that I knew contained direct references to books. For example in the song “Some How, Some Way” Jay-Z says, “Look man, a tree grows in Brooklyn,” which is a direct reference to Betty Smith’s successful 1943 novel by the same name. Talib Kweli and Mos Def’s “Thieves in the Night” pays homage to Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye by creating an entire song inspired by the last paragraphs of the novel. Nas’s “2nd Childhood”, is arguably a reference to a paragraph in Black Boy where Richard Wright explains his existence in Chicago being like “a second childhood.” Using more examples like these, I explained to the young men that the best rappers must be highly literate and the mentioning of books in their lyrics was an overstatement of that fact. After the presentation, I continued to think about literacy and Hip-Hop artists. I thought about the songs that I loved, those songs that were vivid and real, which sometimes took me to a distant place, and at other times, a place of familiarity. The best Hip-Hop songs, those that told stories, excited me as great scenes from books did. I came to the conclusion that my favorite MCs were the young black writers for whom I had been searching.

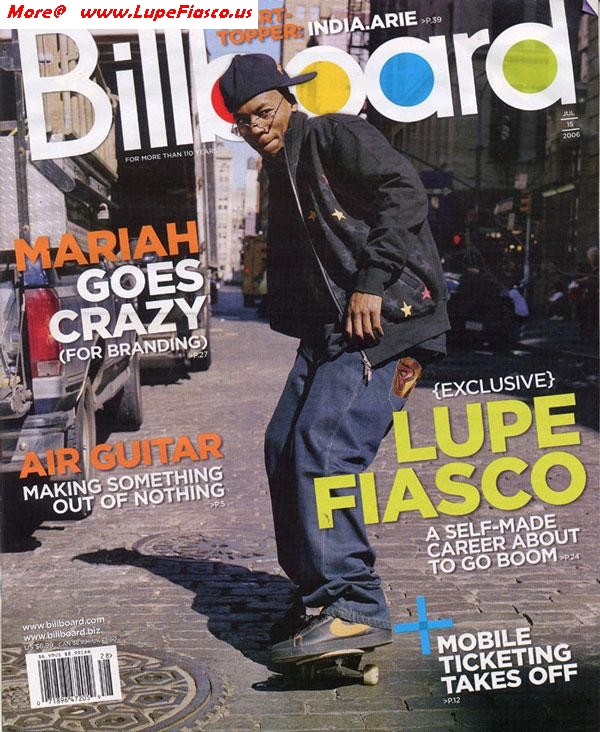

Many compare rappers to poets. However, I believe they should also be compared to writers of fiction. Had it not been for the unique set of circumstances that led to the creation of Hip Hop music, the beats and rhymes making for the most alluring and instantly gratifying form of expression—a fast, natural art form for a fast, tough, uncaring society—many of the greatest MCs would be writers of fiction. No better short stories can be written about the happenings in the ‘hood than Tupac’s heart wrenching “Brenda’s Got a Baby” or Jay-Z’s masterful “Meet the Parents.” How about Scarface’s “A Minute to Pray and a Second to Die” or Slick Rick’s “Children’s Story”? These third person narratives are visual, charged with emotion, and layered with complexity. As for first person rap stories, few are as vibrant and engaging as Will Smith’s early hits like “Parent’s Just Don’t Understand” or even “Nightmare On My Street”. Even recently, Lupe Fiasco’s “Hip Hop Saved My Life,” delivers a well-told story of a young father working toward his big break, dreaming of providing adequately for his family.

Hip Hop’s best artists are modern day American griots. The authentic masters of the art form are the contemporaries I had been looking for. There is a strong correlation between the significant decline of literary works produced by young black men and the creation of Hip Hop in the late 70s. William Faulkner said, “A writer needs three things: experience, observation, and imagination—any two of which, at times any one of which—can supply the lack of the others.” For a number of reasons, would-be, young black fiction writers turned to telling stories through rhymes instead of the longsuffering and painstaking process of learning to craft stories on the page. This explains the near thirty-year decline in literary production by young black men, but it does not provide a solution for filling the existing void. By no means is Hip Hop music sufficient in replacing contemporary works of literature produced by young black men. The emergence of Hip Hop music demonstrates the literary want, the genius, emanating from the most underserved communities. Yet, even with this brilliance, musical genres fade and art forms should support not replace one another. Today, in many black communities the children, boys in particular, are not receiving the proper support and encouragement regarding literacy. The effects are detrimental, causing regression and other sinister occurrences. To encourage the reading and writing of books is to encourage evolution. A good book demands thought and feeling like no other art form and thoughtful writing has always enriched the whole of a civilized society. We must continue to find creative and engaging ways to introduce the wonders of reading and writing to black children of underserved communities. A society falls with the failings of its less fortunate people. With s.m.i.l.e.’s publication, I hope to add to America’s cross-cultural storytelling tradition, which was fortified by those who inspired me, those storytellers in literature and in Hip Hop.

Hip Hop’s best artists are modern day American griots. The authentic masters of the art form are the contemporaries I had been looking for. There is a strong correlation between the significant decline of literary works produced by young black men and the creation of Hip Hop in the late 70s. William Faulkner said, “A writer needs three things: experience, observation, and imagination—any two of which, at times any one of which—can supply the lack of the others.” For a number of reasons, would-be, young black fiction writers turned to telling stories through rhymes instead of the longsuffering and painstaking process of learning to craft stories on the page. This explains the near thirty-year decline in literary production by young black men, but it does not provide a solution for filling the existing void. By no means is Hip Hop music sufficient in replacing contemporary works of literature produced by young black men. The emergence of Hip Hop music demonstrates the literary want, the genius, emanating from the most underserved communities. Yet, even with this brilliance, musical genres fade and art forms should support not replace one another. Today, in many black communities the children, boys in particular, are not receiving the proper support and encouragement regarding literacy. The effects are detrimental, causing regression and other sinister occurrences. To encourage the reading and writing of books is to encourage evolution. A good book demands thought and feeling like no other art form and thoughtful writing has always enriched the whole of a civilized society. We must continue to find creative and engaging ways to introduce the wonders of reading and writing to black children of underserved communities. A society falls with the failings of its less fortunate people. With s.m.i.l.e.’s publication, I hope to add to America’s cross-cultural storytelling tradition, which was fortified by those who inspired me, those storytellers in literature and in Hip Hop.