Who’s Afraid of George Walker

Who’s Afraid of George Walker?

George “Nash” Walker (1872-1911) was born in the aftermath of The Civil War in Lawrence, Kansas, the launching point of John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry, Virginia in the fall of 1859 and site of Quantril’s Raid in the summer of 1863. The post-Civil War demographics and abolitionist politics of the region empowered Walker in historically unprecedented ways and compelled him to transcend the limited expectations of Black people in the United States. He left Lawrence in 1893 with a medicine show and met Bert A. Williams (1874-1922) in San Francisco, California later that year. Soon after forming a partnership that would last seventeen years, the two were hired to appear as Africans in what was essentially a human zoo as part of the Midwinter Exposition in San Francisco until the “Real” Africans arrived from Dahomey.

In meeting the Dahomeans, George Walker and Bert Williams experienced majesty, sovereignty and beauty from an African point of view, one that did not acknowledge White exceptionalism or superiority. This inspired them to, in the words of Paul Lawrence Dunbar, “wear the mask,” and embrace the moniker of, “The Two Real Coons.” In place of the luxury of preference, this choice was designed to draw in crowds and utilize the liminality of the dramatic stage to subversively exploit the contextual difference between the satire of their brand of comedy and the mockery of the minstrel tradition. Under the cloak of entertainment, this philosophy provided space to erode White exceptionalism that was/is a feedback loop of ignorance informed by the arrogance of unearned privilege. When people paid to see minstrel-style cooning, they surely got it and much more. The “more” was George’s understandably problematic, yet unprecedented insistence that audiences receive curated, Black entertainment that was full of universal examples of the human condition told from a uniquely Afro-American perspective.

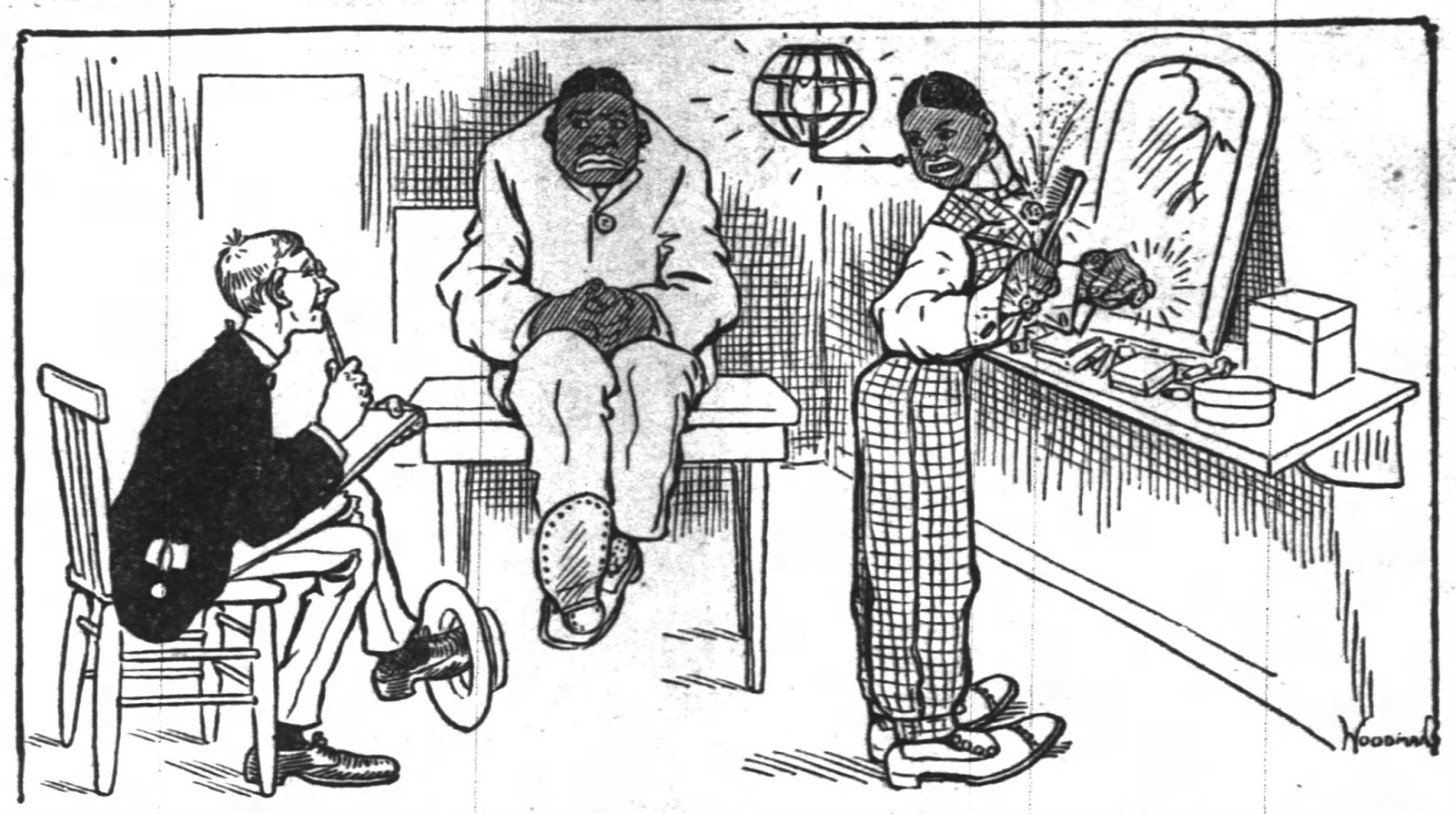

George demonstrated that he was less willing to suffer fools than his partner, particularly when it came to well-meaning, White supremacists. One of the most prominent examples is a drawing from a Chicago Inter Ocean article from June 24, 1906 titled, What Williams and Walker Think of [Thomas Dixon’s] The Clansman. In the drawing, Bert is depicted as insecure and slumping in stereotypical (acceptable) fashion and George is depicted as vain, ungrateful, materialistic, and disrespectful when asked to explain his perspective as a person of double consciousness to a person of privileged, single consciousness. This was echoed by an editorial that George published in The Theatre magazine in August of that same year, titled “The Real Coon of The Stage,” in which George explains the reason for his philosophy of double consciousness: “Black-faced white comedians used to make themselves look as ridiculous as they could when portraying a ‘darky’ character. In their make-up they always had tremendously big red lips, and their costumes were frightfully exaggerated. The one fatal result of this to the colored performers was that they imitated the white performers in their make-up as ‘darkies.’ Nothing seemed more absurd than to see a colored man making himself ridiculous in order to portray himself.” Simply put, George was one of the first—and best–to publicly exploit the notion coined by bell hooks, that, “Margins have been both sites of repression and sites of resistance.” Then as now, his uncompromising nature did not endear him to the powers that be.

Walker was uncompromising in how he chose to represent himself as a Black man, both onstage and off. As a result, he has been largely expunged from historical discourse, especially when compared to the amount of scholarship that has been devoted to Bert. Bert, after all, lived eleven years after George’s death. More important, when the two worked as a team, Bert was the “funny one,” cast in blackface as a non-threatening (and therefore acceptable) loser. This paved the way for him to be granted “Honorary Whiteness” and become the fly in the ointment in the Ziegfeld Follies until just before his own death in 1922.

More than a century after Walker’s death, Black people are still engaged in the same fight against a further entrenched and encoded resistance to Black sovereignty. At the dawn of the twentieth century George Walker and many others attempted to address this cultural cancer and ultimately paid the price in both having to fight twice as hard to get half as far and to have that fight expunged from the record after he was no longer able to stand up for himself. The question is, why? If the United States is truly interested in dealing with the fundamental birth defect of institutionalized White supremacy, the life struggle of George Walker is one of many stories that we need to engage with. As Herbert Apthecker said, “deny the existence of resistance and one negates the dynamic, the soul, the reality of history.”