We Do Language: Nikki Giovanni A 2019 Legacy Seminar Encounter

Categories: Guest Blogger

The Furious Flower Poetry Center has held biennial summer legacy seminars since 2009 (with a hiatus in 2013 and 2015), a focused opportunity to study the work of a living poet. Beginning with Lucille Clifton, seminars have been held on Sonia Sanchez (2011) and Yusef Komunyakaa (2017). As the nation’s only center devoted to Black poetry, Furious Flower’s choice of Nikki Giovanni for the June 2019 seminar gave many a chance to witness the legacy of performing and presenting against well-worn academic notions of conference-going rhetorical practice. As noted by the Washington Post as far back at 1994, Furious Flower, the vision of founder Joanne Gabbin, is not interested in giving us “. . . just another academic conference, dominated by the presentation of papers and trade gossip,” but has always infused “bongos,” “an ancestral praise chant” and “heavyweight academic sessions with cerebral titles like ‘African American Poetry and the Vernacular Matrix.

The structure of the seminar-event was like none other I have seen. Scholars of Nikki Giovanni’s work and teachers looking for professional development, and graduate students like me could expect the guest of honor throughout the entire event, the living legend herself: Nikki. Now and again her long-time friends would drop in, like Val Gray Ward arts activist, playwright, and producer.

Embedded in the seminar was a structural challenge to a Western notion of editorial remove by having the subject present for her “objective” and pre-scheduled critique. It challenged presenters to perform their fidelity to the discipline in not holding back pointed critique—essentially, an academic version of “telling it like it is,” right before the person.

What each of the seminar participants took away from the experience is not easily translated into words, and like them, I am still processing. I can share one experience that set the tone for the week as a whole. It occurred on day 1, as Professor Giovanni—who likes to go by just Nikki—spoke during the Guided Reading Discussion. Her thoughts on family, land and living in a close-knit fashion were as much of a political statement for African-Americans as it was her personal experience.

She created a connection between eminent domain and the Bottom in Philadelphia, gentrification in Harlem, and the ghettoization of black people during the Industrial Era to urban centers as massive dispossession—living together and on the land or in the mountains for marginalized communities is an act of resistance.

Nikki spoke, occasionally holding back, it seemed, both tears and invectives when recounting childhood memories of her brother and her grandmother. Her family did get 40 acres and a mule, she told us—and that was “a political statement” (2019).

From the beginning, I think the shimmering smiles, the fluorescent shades of brown, the plurality of women whose minds were, it seemed, visibly abuzz with investigation and inquiry—caught me. Their calm yet peaked faces were sweetened, a blessed assurance that sitting in the moment that was gathered, something would yield. I was slowly enveloped into the amber of the event. I couldn’t yet speak. So, I listened.

Photo Credit: Jamaica Baldwin

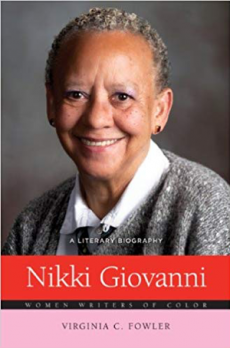

Virginia Fowler is the author of Nikki Giovanni: A Literary Biography (2013) that covers Nikki’s life and work to 2012. Fowler’s work situates Nikki as preeminent within the Black Arts Era, within the changing landscape of American society—as Walt Whitman, too, came to symbolize intentionally and unintentionally both the Civil War and the radical connectivity that resisted a forsaking of nature, land, for industrialization.

Hungry to better contextualize Nikki’s work, I sat up and began taking notes. As my first encounter with this seminar, I was particularly interested in documenting the moment by moment reactions to Nikki being present for the reading of her critical biography.

In my Jeep, I have a CD of Black poetry and oration where Nikki reads “Nikki Rosa.” Everyone knows that famous section in it where she speaks to the future about encroaching biographers:

And somehow when you talk about home / it never gets across how much you / understood their feelings…/ and even though you remember / your biographers never understand / your father’s pain as he sells his stock / and another dream goes / And though you’re poor it isn’t poverty that / concerns you…/ but only that everybody is together and you / and your sister have happy birthdays and very good / Christmases / and I really hope no white person ever has cause / to write about me / because they never understand / Black love is Black wealth and they’ll / probably talk about my hard childhood / and never understand that / all the while I was quite happy

Nikki in the poem, I believe, was worried about a kind of mainstream erasure—also found in the academe—of Black people’s work—work by those deemed controversial or those deemed problematic to the smooth workings of the country’s knowledge creation factories. Nikki in the poem was worried about, as she notes, white biographers who might be tempted to essentialize her early life as gloom and doom—while missing the point that overcoming in the Black family is as simple as choosing to love anyhow. That’s how the work—how the living got done.

Fowler’s presentation was more untraditional than I expected, but the entire conference was already teaching me to shift paradigms of expectations for academic presentation and performativity. It began conversationally and then worked its way into greater chronological specificity. What caused me pause was that the topic centered on familial struggles and spoke about Nikki’s life in a bereft way. There was a conversation about her parents’ divorce, her tense relationship with her brother, fractured relationship with her mother and bouncing from academic institution to institution (2019). She mentioned Nikki’s father repeatedly beating her mother.

I had to step outside midway through and pray. I folded over, onto the floor, on my knees, rocking—as if wailing on the Western Wall. Periodically looking into the sky, I silently wept to say: “What if…What if Nikki wasn’t here? Who would defend her poem? Nikki Rosa? Who would see, in Nikki Rosa, her wanting lions to tell their stories? Of the first-generation college-goer? The mountain, brainy kid? Or me, the part Jew, part Caribbean, part sharecropper’s daughter? Who, too, would see a need to reference that you, she, I had happy birthdays and very good Christmases.”

Upon returning, I refused to sit. I stood. I stood outside the Montpelier Room’s clear doors. I walked to the other side and let the sunshine on my face. I cried out, “Abba, Father.” Nikki was two tables away from where I stood, past the doors and clear dividing panels. In front of Nikki was Fowler and I, behind it all, refused to enter the conversation. In writing poems, the poet, it was said at the conference, births poems and then they belong to the public. In a quiet, silent, contained tantrum, I, in body, refused to turn over, so swiftly, Nikki’s poems. The irony here, of course, is that in “refusing to turn over” the poem, she is in effect claiming it as hers to protect, but she (not being Nikki) is part of the “public” readership of the poem whose claim she refutes!

I was intent on giving “Nikki Rosa” back to Nikki.

I wanted, yes, fidelity to the terror that Nikki experienced growing up, to be tender to those moments. I also wanted a fidelity to the story of Nikki as an overcomer, as a survivor, her stories of escaping the bondage of institutional allegiances for a higher calling—her daring dodge, zigzag life of escaping academic erasure, her triumph over institutional obscurity that poets more and more often find themselves—how she kept close to the people she loved and the people who loved her.

Nikki has continuously reinvented and re-introduced herself to old and new audiences. Nikki’s story couldn’t, then, be one of pity. Nikki’s is a story of redemption, recall—and calling herself back to herself and together again. Nikki is now 76, from the Black Arts Movement and still alive—still writing, teaching and laughing. That is a triumph…of many very good birthdays.

Just as I was half wondering about speaking beyond deficit-based thinking and what it means to an outsider on the inside of the academe, Nikki stood up.

Nikki started recounting a story about her grandfather, his transition and not wanting to let the facts block readers from the truth. She defied her dean by going to visit her grandfather for Thanksgiving, as it happened, the year before he passed. She spoke about Knoxville, wearing all black, church ladies giving her books for book reports and the sheer understanding of what their sheer appearance means to a young inquisitive girl in the world. She seemed brought back to life.

Then she sat back down and let the biographical reading continue. I looked and squinted at Nikki. Was she tapping into a newly cracked ceiling in the room? Of young women silently saying they also will make sure to not lose the forest for the trees.

When what it means to be a scholar, a woman, and Black is hard to reconcile in the Western context, transgression appears. Those transgressions mark a distance or remove from one’s family or kin-group that is visibly lonely, hard on the body and spirit and fracturing to one’s work—due to the migrancy that the academic life requires. Nonetheless, she persisted.

For the first time, many attendees remarked, they saw Nikki cry…and how she kept on crying. Maybe after hurdling all those hoops of social strata, knowing the rings of terror embedded in them—may be her tears were to say: “I, poet, have called a gathering—from poems no longer my own but mine enough to return me some rest and reflection—that in living a life, I chose to live and not die.”

Shayna S. Israel is a poet interested in the intersection between visual and literary arts. She is currently a Ph.D. student in Creative Writing at the University of Kansas and an affiliate of HBW. At KU Shayna teaches introductory English courses to undergraduate students. Her previous teaching experience includes instructing in non-traditional settings, working in after school programs and facilitating technical writing courses for visually impaired and differently-abled students.

Shayna S. Israel is a poet interested in the intersection between visual and literary arts. She is currently a Ph.D. student in Creative Writing at the University of Kansas and an affiliate of HBW. At KU Shayna teaches introductory English courses to undergraduate students. Her previous teaching experience includes instructing in non-traditional settings, working in after school programs and facilitating technical writing courses for visually impaired and differently-abled students.