This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

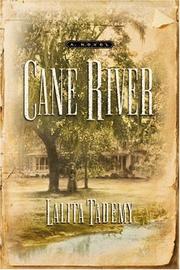

Viewing Cane River

Lalita Tademy’s novel

Cane River (2001)

appeared nineteen years

after Horace Jenkins’

film.

[By: Jerry W. Ward, Jr.]

Monday, October 22, 2018, was a special day in the year-long celebration of three hundred years of history in New Orleans, because we had the privilege of seeing a remarkable instance of black film in the history of cinema in the United States of America. We saw Horace Jenkins’s Cane River (1982), a major feature of the 29th New Orleans Film Festival (NOFF) at the Contemporary Arts Center.

There is nothing unique in the fact that African Americans have written, directed, and produced film. We need only remember the pioneering work in independent film of Oscar Devereaux Micheaux (1884-1951), who wrote, produced , and/or directed more than 44 films, classics in the visual reproduction of race, or of William Greaves (1926-2014) who produced more than 200 documentaries and whose Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968) illuminated post-modernity before the post-modern was born. The contemporary filmmakers we applaud—-Julie Dash, Spike Lee, Louis Massiah, Ava Marie DuVernay and others—are not bereft of noble ancestry. They are not bastards from nowhere. They, like Horace Jenkins (1941-1982), are heirs of universal African creativity and people who created a pathway for Barry Jenkins, the Oscar-winning filmmaker of Moonlight and the 2018 adaptation of James Baldwin’s 1974 novel If Beale Street Could Talk. What seems to be unique (one is tempted to say “uncanny”) about viewing Cane River in the Age of Trump is a recognition that love is stronger than lust and that when African Americans make things for African Americans, magic materializes. It is premature to say, even from a pre-future vantage, we are witnessing the dawn of another black renaissance. It is not irrational, however, to think we might be blessed with renewal by virtue of temporal-spatial accidents.

To put the matter in an acorn, I quote the paragraph on Cane River from the NOFF catalogue, p. 29:

“Cane River, the beautiful long-buried movie written and directed by Horace Jenkins in 1982, comes to life again for the first time in 36 years since the director’s sudden death. A Romeo & Juliet love story, Cane River is set near Natchitoches, in one of the first ‘free communities of color.’ Richard Romain plays Peter Metoyer, home to fight for his land, and Tommye Myrick plays the headstrong Maria Mathis, reluctant to succumb to his charms just because he’s the scion of a famous family. Together they confront schisms of class and color that threaten to keep them apart and that still roil American today. A must see lost treasure of Louisiana film history. New 35mm archival print by the Academy Film Archive, mastered in 4k by IndieCollect support from the Roger & Chaz Ebert Foundation.”

This is the language of promotion that is to be supplemented and critiqued by the language of probable “truth” articulated by spectators in 2018. What we will hear ourselves saying to ourselves has little to do with a Shakespearean foil and everything to do with the fact that the famous Rhodes family of New Orleans put up the money in 1982 for Jenkins to make the film; that Cane River is a tender romance, a counterweight to the harsh tragedy suffered since the advent of the Atlantic slave trade; that there is a bittersweet “backstory” regarding the making of Cane River that one can only get from Chakula Cha Jua, who is a brilliant griot-historian of 20th century cultures in New Orleans, from members of the Rhodes family, and from actors in the film, those who were present at the creation; that the vexed subject of being Creole (of whatever complexion) is at the core of those narratives which ensure that living in New Orleans will always be a blessing and a curse. Seeing Cane River is a reason for having a robust objective/subjective conversation.

Jerry W. Ward, Jr. is Professor Emeritus of English at Dillard University, Honorary Professor at Central China Normal University, and HBW Board Member (Emeritus).