This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

Toi Derricotte’s Open Confession

Open confession — public broadcasting of once private spiritual desire and/or agony — may be good for the soul. As far as contemporary American poetry goes, whether open confession is a many splendid thing or a depressing invitation to tour another person’s dread and suffering is debatable.

Open confession — public broadcasting of once private spiritual desire and/or agony — may be good for the soul. As far as contemporary American poetry goes, whether open confession is a many splendid thing or a depressing invitation to tour another person’s dread and suffering is debatable.

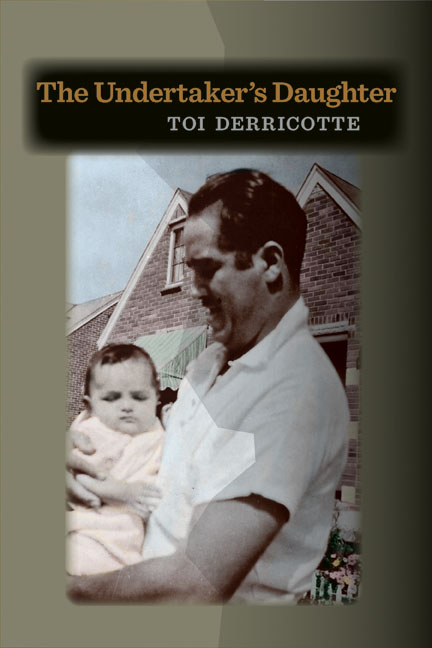

The poetic mode identified as confessional is as ancient as the Epic of Gilgamesh and as modern as Toi Derricotte’s The Undertaker’s Daughter (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011). In African American poetic tradition, poets as diverse and different as Gwendolyn Brooks, Lenard D. Moore, Wanda Coleman, Pinkie Gordon Lane, Kalamu ya Salaam, and Robert Hayden have confessed. What does it profit you to

add the burden of another’s psychological/metaphysical dread to your own? Is the dread imaginary or real? Is the confession a hook to catch the reader, to bait her or him? What is the profit in peeping through the keyhole of language at the intimate violence behind the door, the eternal agon resurrected by memory?

These questions worry your reading of The Undertaker’s Daughter. Derricotte invites you to compare her performance with that of Sylvia Plath’s famous book of confessional poems Ariel (1965), especially the poem “Daddy.” She bids you to recall Richard Wright’s “lifelong mental suffering, and how those experiences fueled his writing” (88). Derricotte’s prose and poems in her most recent book are provocative.

The blurbs or authenticating testimony provided by Yusef Komunyakaa, Natasha Trethewey, and Terrance Hayes speak of “a chiaroscuro of hue and emotion,” of exploring “the nature of inheritance – its legacies of language and cruelty and sorrow,” and of “acuity and grace.” As supporting agents for Derricotte’s open confession, the blurbs remind you of a grave matter.

Social networking has minimized the nobility of privacy. The Undertaker’s Daughter reminds you that privacy will be a luxury for the powerful and wealthy in a future. It is fitting to allow Shakespeare’s Iago to have the final words: “I say put money in thy purse.” (Othello I.iii)