This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

Toasts, Black Women, and Hip Hop

The canon of African American literature overflows with stories of Stagolees, Shines, and Signifying Monkeys. These antiheroic figures in African American culture created the paradigm for the poetic form known as the toast. Derived from black folklore, toasts are narratives in which a character overcomes a sequence of events. In doing so, they illustrate their extraordinary physical and lyrical abilities. Usually told by male personas, they function to attest to one’s street credibility and physical abilities.

The canon of African American literature overflows with stories of Stagolees, Shines, and Signifying Monkeys. These antiheroic figures in African American culture created the paradigm for the poetic form known as the toast. Derived from black folklore, toasts are narratives in which a character overcomes a sequence of events. In doing so, they illustrate their extraordinary physical and lyrical abilities. Usually told by male personas, they function to attest to one’s street credibility and physical abilities.

The lack of attention to women’s toasts would lead one to believe that women are not participants of this tradition. In some ways, this assumption could be valid. For one, the toast can be said to come from prison culture, which is most commonly associated with black, males. Secondly, none of the ideal toast characters are women, however, women are often the subjects of insult. This is seen in “the dozens” a form of toast where two or more people, usually black men, set out to verbally annihilate an opponent by telling wise quips about the other person and/or their relative usually their mothers. I find this particularly ironic for two reasons. I find this ironic because black women have long been praised for their durability and strength. Black women are also thought to be sassy and witty. Where, then, are the braggadocios women?

Black women do have a presence within this toast tradition, though there stories may not often fit into traditional rhyming poem with multiple episodes. One of the most well known toasts by a black woman is Nikki Giovani’s “Ego Trippin.” Other toasts written by black women are “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou and “Kissie Lee” by Margaret Walker. With the exception of “Kissie Lee” which is a female version of “Stagolee,” the narrators in these toasts are nameless and thus function to empower black women as a whole.

I would argue that women have utilized the toast tradition more in music. It is possible that the first traces of women in the toast tradition are in the blues. While the blues is known for telling stories of love and hardship, there are some female blues musicians who adopted some form of the “badwoman” figure in their works. For example, Bessie Smith confesses to killing her lover in “Send Me to the ‘Lectric Chair.” Though she shows remorse, which is not conventional in the toast tradition, the way in which she describes how she killed him is parallel to the story of Stagolee who kills a man over a Stetson hat.

I would argue that women have utilized the toast tradition more in music. It is possible that the first traces of women in the toast tradition are in the blues. While the blues is known for telling stories of love and hardship, there are some female blues musicians who adopted some form of the “badwoman” figure in their works. For example, Bessie Smith confesses to killing her lover in “Send Me to the ‘Lectric Chair.” Though she shows remorse, which is not conventional in the toast tradition, the way in which she describes how she killed him is parallel to the story of Stagolee who kills a man over a Stetson hat.

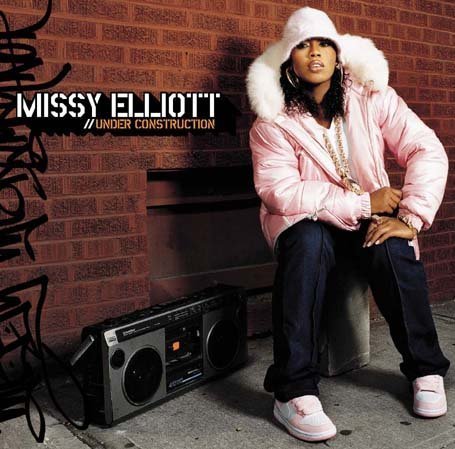

In Hip Hop, it is common for rappers and MCs to boast about unsavory acts. The common misconception is that people are attracted to these violent or immoral acts. I would argue, however, that the appeal of this form of Hip Hop is not so much in what the narrator speaks of doing as much as it is how the narrator is describing what’s being done. Likewise, the appeal of someone talking about him or her self is in the way they describe themselves. One great example of this Missy Elliot’s song “Gossip Folk,” a response to rumors spread about the artist.

In this song, she directly addresses the insignificance of the rumors by opening the song with a host of voices gossiping about the artist. Her rap begins with her bragging on her fame and riches. Verbally, she uses an intricate rhyme scheme and plays with rhythms and sounds to demonstrate her talent for language and word manipulation. Case in point, the chorus is a set of indecipherable gibberish that resembles a conversation.

Hip Hop, then, has served as a great medium through which women have created masterful toasts. Some declare women’s strength while others are insults to fellow rappers. In either case, women have most recently used toasts to carve out a space for female Hip Hop artists and demand respect within a male dominated culture. In the blog to follow, HBW will acknowledge five female music artists that employ toasts in their works.