This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

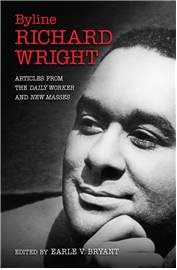

Subversive Journalism: A Review of Earle V. Bryant’s BYLINE RICHARD WRIGHT: ARTICLES FROM THE DAILY WORKER AND NEW MASSES (2015)

Such recent dedicated scholarship as Mary Helen Washington’s The Other Blacklist: The African American Literary and Cultural Left of the 1950s and William J. Maxwell’s F.B. Eyes: How J. Edgar Hoover’s Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature serve as a warrant for thinking of contemporary literary and cultural studies as components of a mega-surveillance machine. Readers and critics cooperate, often unwittingly, with publishing conglomerates and official agencies of detection in panoptical activities that exceed the scrutiny imagined by Michel Foucault in Discipline and Punish or by Edward Said in Culture and Imperialism. Technological progress encourages us to abandon dreams of a liberated future and to accept dystopia as self-evidently “normal.”

For Richard Wright scholars, the forthcoming 2016 publication of Indonesian Notebook: A Sourcebook on Richard Wright, Modern Indonesia, and the Bandung Conference, by Brian Russell Roberts and Keith Foulcher, will create an opportunity for more speculation about the function of journalism in Wright’s imagination, as well as raising devastating questions about how the journalism of Ida B. Wells and Ishmael Reed assist us in understanding what was and is African American literature. We do need to explore Black print cultures more thoroughly in relation to the production of Black literatures. In this sense, Earle V. Bryant’s long-awaited Byline Richard Wright: Articles from The Daily Worker and New Masses has a significant mediating function.

Perhaps financial exigencies are responsible for the University of Missouri Press’s delayed printing of Bryant’s editing and commentary on a number of Wright’s Daily Worker articles from 1937 and the New Masses’ essays “Joe Louis Uncovers Dynamite” (1935) and “High Tide in Harlem: Joe Louis as a Symbol of Freedom” (1938). Bryant, a Professor of English at the University of New Orleans, had been working on this project, very quietly, for more than a decade. The delayed publication does not compromise his effort to map underexplored territory in Wright Studies. It does, unfortunately, increase the likelihood that his work will get less attention than it deserves.

Giving notice to time and space, as Thadious M. Davis does in Southscapes: Geographies of Race, Region, and Literature (2011), reifies the value of chronology in examining Wright’s growth. Her methodological choices ensure that we link Wright’s emergence as a journalist with his assignments in subdivisions of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), especially the Illinois Writers Project, without diminishing notice of his simultaneous participation in Chicago’s South Side Writers group and brief membership (1934-35) in the John Reed Club. However, Bryant chose to arrange the Daily Worker articles by theme–urban conditions in New York, war in Spain and China, heroism, Marxist interest in the Scottsboro case, and art in the service of life. By avoiding strict chronology, Bryant is able to foreground his insightful analyses of political implications and aesthetic qualities in Wright’s journalism to tell us many things about the strengths and weaknesses of Wright’s accomplishments. Byline is Bryant’s effort “to bring Wright’s early newspaper work out of obscurity and into the light where it can be read and appreciated” (10).

There is a mixed blessing in Bryant’s book being in our hands after the works by Washington, Maxwell, and Davis, as the rigor of their scholarship sets the bar for critical attention to Wright very high. Bryant’s work provides an opportunity to think about how African American and left-leaning journalism has been necessarily subversive and critical of efforts to sell the American Dream. To be sure, Byline encourages more thinking about how subversion operates under surveillance. The minor failure in Bryant’s scholarship, however, lies in his decision not to supply a full listing of all the Daily Worker articles Wright wrote and glosses or explanatory footnotes for the articles selected from the full range of what is available. Yes, students and scholars who might use Bryant’s book can surf the Internet to get information about topical references in the articles, but Bryant would have enhanced the value of his book by supplying them in the text. For example, it is odd that Bryant chose to say nothing about what Wright might have learned from Frank Marshall Davis about the art of journalism. It is even odder that H. L. Mencken is not mentioned in Byline because Wright made a special point of acknowledging his discovery of Mencken in a Memphis newspaper and his indebtedness to the work of Mencken as one of America’s most influential journalists, prose stylists, and social critics. And it is baffling that Bryant seems to attribute the claim “All art is propaganda” to Wright on page 215, when it is a widely known that W. E. B. DuBois used that wording in his essay “Criteria of Negro Art” in the October 1926 issue of Crisis.

Shortcomings notwithstanding, Byline Richard Wright: Articles from The Daily Worker and New Masses can quicken interest in exploring more profoundly the journalistic aspects of Black Power, The Color Curtain, and Pagan Spain and Richard Wright’s bracing subversiveness. Wright deserves more credit for his prophetic panopticism.

Jerry W. Ward, Jr.

April 11, 2015