This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

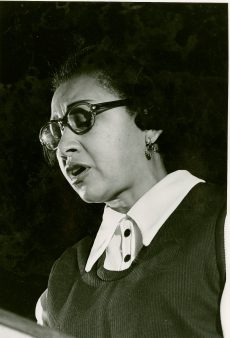

The Stone that the Builder Refused: An Interview with Naomi Long Madgett

The black women’s literary renaissance of the 1970s saw the emergence of some of today’s most accomplished black women writers: Maya Angelou, Toni Cade Bambara, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Rita Dove, Maya Angelou, among them. On the heels of — and often inspired by — the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, black women writers carved out their own space, ushering in a period of continuous productivity. Their writing addressed race, gender and class, exploring a fuller, more multidimensional black womanhood and black women’s identities. Though some of the best-known black women writers saw their careers burgeoning during this period, there is one influential figure whose name is rarely remembered as part of the canon: Detroit Poet Laureate, educator, and founder and editor of Lotus Press, Naomi Long Madgett.

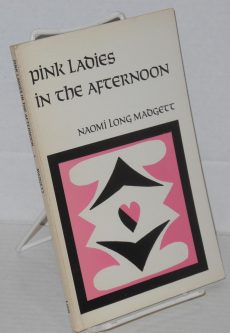

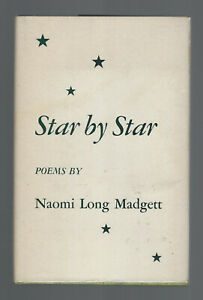

Notably, Madgett began writing and publishing much earlier than Toni Morrison or Alice Walker. Her first poetry collection Songs to a Phantom Nightingale (1941) was published when she was only 17. Her next volume, One and the Many, followed in 1956. In 1970, to that prestigious corpus of work produced by black women writers, Madgett added her third volume of poetry Star by Star (1970) and two years later, Pink Ladies in the Afternoon. With four volumes of poetry, she was one of the headliners at the 1973 Phillis Wheatley Festival, organized by her friend and fellow poet Margaret Walker. Before the end of the decade, Madgett had published her fifth volume Exits and Entrances (1978) a volume exploring race, class, and gender in earnest.

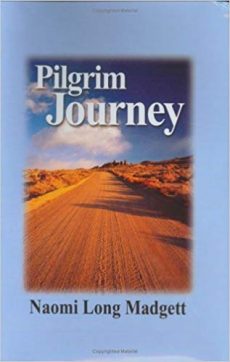

After reading Madgett’s poetry and her autobiography Pilgrim Journey (Broadside Lotus Press, 2006), I was struck immediately by the range of her topics and questioned why she had not received more critical attention. During our interview in July 2017, she discussed her own experiences as a woman poet, especially the difficulties finding a publisher for her fourth collection Pink Ladies: “That was during a period when everything was rage and anger. Nobody seemed to be interested in that poetry [that focused on black women’s experiences beyond race] . . .either you were too black or not black enough and I wasn’t black enough. But I was determined to get the book published…”

Madgett describes the importance of the volume in Pilgrim Journey. Pink Ladies “dealt with race in more subtle ways, as well as the experience of being a woman, a divorcee, a single mother, a sister, a daughter, a friend, and an observer of life as a total human being” (313-14). She told me that it was a somewhat accidental impetus for the creation of Lotus Press in Detroit, which she founded in 1980. In 2015, Lotus merged with Broadside Press, established in 1965 by friend and fellow poet Dudley Randall. Though Madgett was interested in exploring issues facing black women beyond race, the name of her new press established it as a home for black writers in whose work other presses were not interested: “I came up with the name of the new press, ‘Flower of a New Nile.’ In other words, black poetry transplanted to American soil.” Supporting black artists was and has always been Madgett’s goal as an editor.

Her opening poem in Pink Ladies, “Dedication,” expresses her self-determination within an ambiguous context. It encourages the reader to move beyond racial themes in order to claim her identify, exemplified in the lines, “Yet so sure were they and I/I was not doomed to die/That one bright flower burst through blight to bloom.”

Self-determination and self-definition were both distinguishing features in the literature of the black women’s literary renaissance. Although the writers emerging during the Black Arts Movement were diverse, the more explicitly political goals and the concept of “the black aesthetic” drew the most attention. Writers like Madgett, however, gave a more nuanced meaning to “political” writing, what it was and could be. Madgett dislikes the term political because it is often laden with assumptions—about form, the author, and more. She offered this explanation of her view of political poetry when I sat down with her: “This goes back to the period [during the social protest novel period of the 1930s and 40s and the later Black Arts Movement] when a lot of black poets thought everybody ought to be political—all black poets should fight the battle. I don’t fight battles in my writing. There are other ways of doing it. Some are very political, very specific, but most of all the references to race are subtler. That’s the way I write.”

Though Madgett rejects the idea of imposing limits on the subject matter for poets, especially black poets, and defining them exclusively by their phenotypical characteristics, whether race, gender, or class, she acknowledges that certain poets fully embraced the need to be explicitly political and/or distinctively black. Throughout the interview, Madgett referenced her friendship with poet Gwendolyn Brooks, with whom she exchanged letters, now housed with her archives at the University of Michigan Special Collections Library. Madgett, however, was less enthusiastic about Brooks’ later work. “. . . there was something that one particular poet said who I won’t identify . . . but he was one that felt we all needed to be political and we all needed to fight the battle in our poetry. It was a very divisive attitude . . . Gwendolyn Brooks’s later poetry would have been better if she hadn’t fallen into that trap . . . That was just not my choice.”

Though Madgett rejects the idea of imposing limits on the subject matter for poets, especially black poets, and defining them exclusively by their phenotypical characteristics, whether race, gender, or class, she acknowledges that certain poets fully embraced the need to be explicitly political and/or distinctively black. Throughout the interview, Madgett referenced her friendship with poet Gwendolyn Brooks, with whom she exchanged letters, now housed with her archives at the University of Michigan Special Collections Library. Madgett, however, was less enthusiastic about Brooks’ later work. “. . . there was something that one particular poet said who I won’t identify . . . but he was one that felt we all needed to be political and we all needed to fight the battle in our poetry. It was a very divisive attitude . . . Gwendolyn Brooks’s later poetry would have been better if she hadn’t fallen into that trap . . . That was just not my choice.”

And though Madgett may not agree with Brooks’s later work, she accepts a fundamental facet of black women’s writing during the black women’s renaissance — there was no one way to write about or define black womanhood. Alice Walker makes a similar point in “Saving the Life That is Your Own: The Importance of Models in the Artist’s Life,” an essay from her foundational collection In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens (1983). Walker writes, “What is always needed in the appreciation of art, or life, is the larger perspective. Connections made, or at least attempted, where none existed before, the straining to encompass in one’s glance at the varied world the common thread, the unifying theme through immense diversity, a fearlessness of growth, of search, of looking, that enlarges the private and public world” (5).

And though Madgett may not agree with Brooks’s later work, she accepts a fundamental facet of black women’s writing during the black women’s renaissance — there was no one way to write about or define black womanhood. Alice Walker makes a similar point in “Saving the Life That is Your Own: The Importance of Models in the Artist’s Life,” an essay from her foundational collection In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens (1983). Walker writes, “What is always needed in the appreciation of art, or life, is the larger perspective. Connections made, or at least attempted, where none existed before, the straining to encompass in one’s glance at the varied world the common thread, the unifying theme through immense diversity, a fearlessness of growth, of search, of looking, that enlarges the private and public world” (5).

Madgett followed her exaction of Brooks with her driving motivation as a poet. She had a successful career as an editor in the Detroit Public School System, where she taught the first creative writing course and first black literature course. But it was Madgett the editor and critic who summed it up for me. “[Black poets] write in different styles and about different subject matter, but there is a place for all poetry. We don’t have to be alike. Any effort to try to make us all alike is more destructive than it is anything else.”

Madgett followed her exaction of Brooks with her driving motivation as a poet. She had a successful career as an editor in the Detroit Public School System, where she taught the first creative writing course and first black literature course. But it was Madgett the editor and critic who summed it up for me. “[Black poets] write in different styles and about different subject matter, but there is a place for all poetry. We don’t have to be alike. Any effort to try to make us all alike is more destructive than it is anything else.”

The full interview with Naomi Long Madgett will appear in a forthcoming issue of The Langston Hughes Review.

Morgan McComb earned her MA in English Literature and Literary Theory from the University of Kansas in May 2019. Her research focuses on Black poetry since the Black Arts Movement.