This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

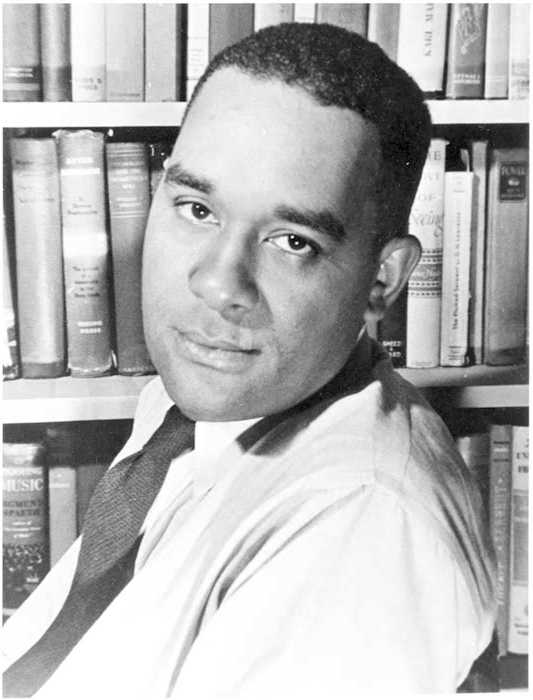

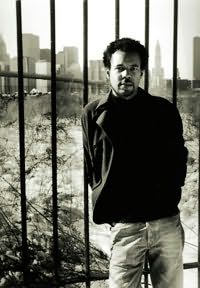

The Significance of Early Support For Novelists: Richard Wright & Colson Whitehead

There are some notable similarities between the early literary careers of novelists Richard Wright and Colson Whitehead. In particular, the early, substantial support and endorsements that they received for their first published novels were remarkable and helped established them as notable literary figures.

Wright’s Native Son (1940) was published by a major publisher (Harper & Bros.) and was a Book-of-the-Month Club selection, which ensured that his book would receive wide circulation and considerable attention.

Wright’s Native Son (1940) was published by a major publisher (Harper & Bros.) and was a Book-of-the-Month Club selection, which ensured that his book would receive wide circulation and considerable attention.

When Colson Whitehead’s The Intuitionist was first published in December 1998, it did not shake up the literary world the way Native Son did, but it did begin gaining attention fairly quickly. Whitehead’s novel was published by Doubleday and received positive reviews in places like Time and The New York Times.

Wright and Whitehead were 31 and 29, respectively, when their debut novels first appeared. The numerous positive, well-placed reviews that they received had to be personally satisfying and encouraging for the two young men. From a business standpoint, the literary acclaim that the novelists gained ensured that they would continue receiving support from their publishers.

In fact, their publishers would continue to view the novelists and their first novels as valued assets. Among other things, the support from their publishers meant that Wright and Whitehead had the freedom to think about writing and not on the issue that so often preoccupies authors’ time and energy: getting published.

In fact, their publishers would continue to view the novelists and their first novels as valued assets. Among other things, the support from their publishers meant that Wright and Whitehead had the freedom to think about writing and not on the issue that so often preoccupies authors’ time and energy: getting published.

Considerations of Wright’s and Whitehead’s common publishing histories are especially fascinating when we note their different eras and the differences between the general tones and styles of their writings. Lila Mae, the highly-educated black woman, elevator inspector protagonist in Whitehead’s first novel is quite dissimilar from Bigger Thomas from Wright’s Native Son.

Despite the differences however, the particulars of their overlapping histories, especially the early substantial support that they received, remind us that publishing factors – not simply authors’ writing – go a long way in the production of major black writers.