This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

Seeing the Monsters Among Us

[By: Jane’a Johnson]

I have often wondered why I like watching horror movies and reading horror fiction. I do not like violence. In fact, quite the opposite. I can barely stand to watch blood and guts. Psychological distress, too, is hard for me to bear. Still, I soldier on, watching most of the newest horror releases in theaters and on streaming services, buying novels new and old with words like “terror” and “vampire” in the titles. Sometimes even their covers say “blood and bone”.

I enjoy the supernatural and the preternatural, things which are either obvious or just outside the bounds of explanation. But this is not why—at least not all of the reason why—I’m interested in horror. It is only part of the story.

Philosopher and horror scholar Noël Carroll has argued that horror stories are not defined only by the feelings they elicit, but by slowly revealing narrative secrets. Horror stories, according to Carroll, are, “dramas of iterated disclosure”. Is the monster real or not? Is our protagonist just imagining things?

We, of course, know what monsters, murderers, and ghosts do before we consume any story. For what would we be reading or watching it in the first place if we did not expect one to be revealed? Later, after the monster itself is disclosed, the capabilities of the “monster” are dramatized.

These “dramas of iterated disclosure”, that underpin most of the horror genre appeal especially to black audiences, who understand very well that many kinds of monsters can exist without the broad consensus of those around them. One of racism’s most effective tools is denying its very existence, and thus denying all of the monstrosities it is responsible for.

This is why films like Get Out (2017) so appealed to black audiences—not just because it effectively skewered liberal racism and exposed the terror of racism itself, but because it never once insulted its black audience’s intelligence. We knew very well there was a monster all along, and our critical faculties yearn for more stories that respect the time-honed critical faculties of black people. The slasher film in particular, according to Carol J. Clover, is littered with frightening white antagonists pursuing painfully silly white women (there are, of course, some notable exceptions) who then become the twin image of those villains. These protagonists come to mirror both the villains and the imagined audience in Clover’s canonical text, whose shared profile is hardly ever assumed to be black, or female, or both. Michael Myers, Jason, Freddy Krueger, and the puerile protagonists that populate such worlds be damned.

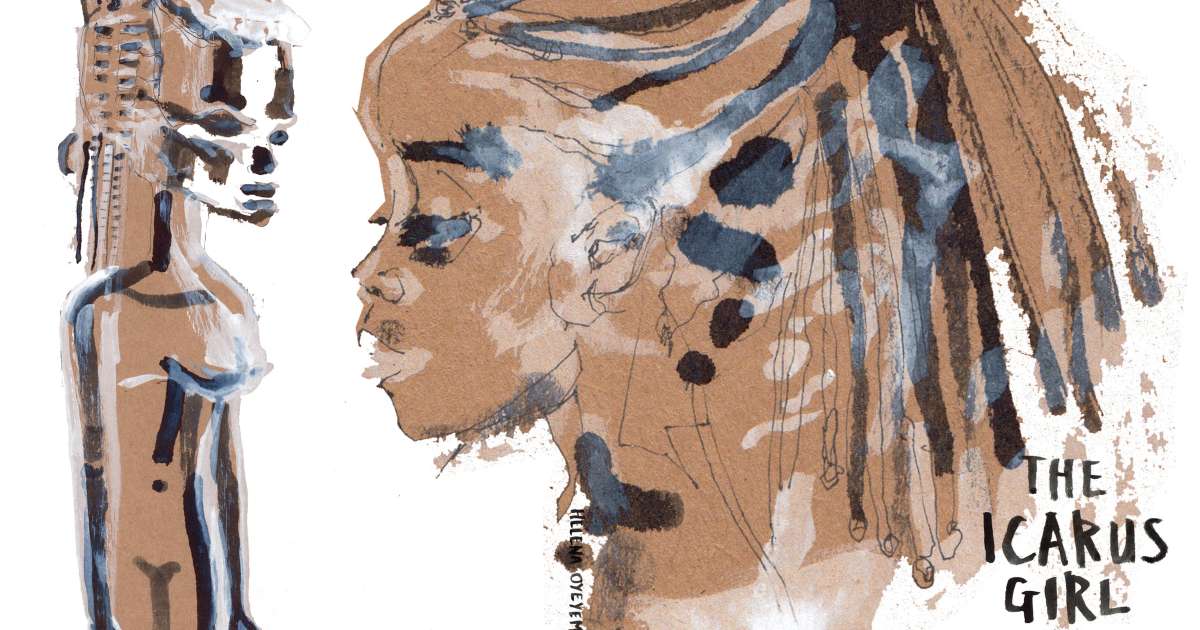

Black horror stories, then, are not merely defined by an active engagement with the horrors of race or black issues more generally, but also by engaging critical faculties engendered in black people because of race. Works like Beloved by Toni Morrison or The Icarus Girl by Helen Oyeyemi, for example, happen to do both.

The effectiveness of using metaphor and the tropes of horror to face things unimaginable, yet lived in some form or another by black people every day, give horror a limitless potential to address in full voice what is sometimes only whispered when we are not among friends. Beloved is a novel about a woman who, during Reconstruction, finds herself in the presence of the grown-up version of a baby she smothered to escape being enslaved. What is Beloved but a ghost story about how the terror of slavery that continues to haunt black people—and by extension all of America—in various ways? It also explores, among other things, one of our most open secrets, brutal sexual violence against black women perpetrated by white men with absolute impunity. It never pretends that there is not a ghost. Morrison knows very well, as we do, that it exists, that it is real. Trauma knows no time, nor does it know space. It is metaphysical, as much as a ghost, a family curse, or fear of the unknown.

How very terrifying to walk out of one’s door every day and be attacked, harangued, harassed, or worse, shot and killed, when you are looking for protection, liberty, and freedom? How horrible to have to trade your voice, and thus yourself, as in the “dark comedy” Sorry to Bother You (2018) for capitalist “success”? Black horror can be absurdist too, even “funny”. It pushes genre boundaries by its very nature, which is part of the reason why Get Out was incorrectly classified as a comedy at the Golden Globes in 2018. Racism, in all of its forms, big and small, psychological and physical, violent and passive aggressive, permeates every facet of our lives here in America. It is truly, utterly, a horror. The reason why I am constantly on the hunt for the supernatural in stories is not because I want to be. I have little choice in the matter; I have to be.

Jane’a Johnson is pursuing a Ph.D. in modern culture and media at Brown University and an MLIS at San Jose State University. She holds a BA from Spelman College in philosophy and an MA in cinema and media studies from the University of California, Los Angeles. Jane’a’s research interests include visual culture and violence, heritage ethics and media archives.