This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

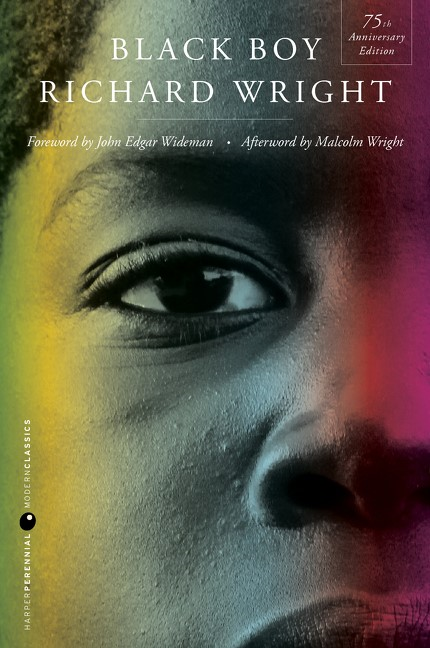

Richard Wright’s ‘Black Boy’ Celebrates 75th Anniversary

Categories: Anniversaries

Credit: Harper Collins

On Tuesday, February 18, Harper Perennial released a new edition of Richard Wright’s classic memoir Black Boy to commemorate the 75th anniversary of that work’s publication. The coming-of-age story, originally published in 1945, chronicles Wright’s upbringing in the Jim Crow South, his eventual move to Chicago and evolution as a major writer through his involvement with the Communist Party. Black Boy explores the ubiquitous concepts of racism, segregation and poverty.

To coincide with Black Boy’s anniversary, Mississippi’s Arts + Entertainment Experience (The MAX) hosted a free screening of HBO’s 2019 film adaptation of Wright’s novel Native Son on Friday, February 21. The event was free and open to the public. Additionally, the first 70 guests received free copies of the new edition of Black Boy.

Credit: The Max

“This was the culture from which I sprang. This was the terror from which I fled.” – Richard Wright, Black Boy (All quotes from Black Boy except where noted)

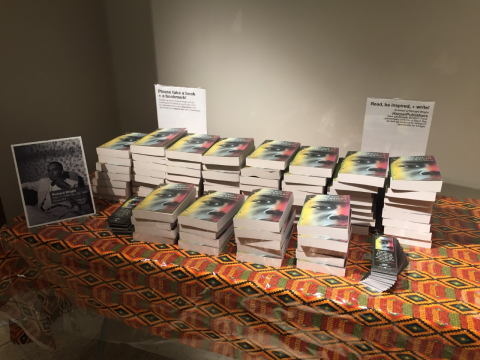

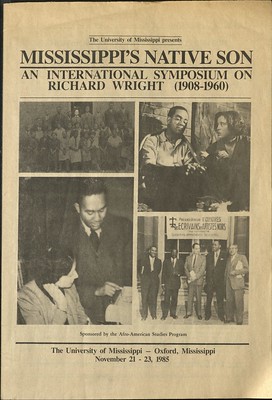

The Project on the History of Black Writing has worked extensively to bring greater attention to the work of Richard Wright in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Twenty-five years after Wright’s death, the Afro-American Studies Program and the Project on the History of Black Writing at the University of Mississippi organized the first international conference on the acclaimed author held in the US. “Mississippi’s Native Son” in 1985 brought students, scholars, writers, and school educators to Oxford, Mississippi for the three-day gathering that signaled Wright’s symbolic return.

!["“Mississippi’s Native Son” Symposium. [From Left: St. Clair Drake, Russell Marshall, and Fern Gayden were friends of Wright in Chicago.]"](/sites/hbw/files/images/hbw-blog/100420/45660999394_4e02f0566b_q.jpg)

“Mississippi’s Native Son” Symposium.

[From Left: St. Clair Drake, Russell Marshall, and

Fern Gayden were friends of Wright in Chicago.]

“I wanted a life in which there was a constant oneness of feeling with others, in which the basic emotions of life were shared, in which the common memory formed a common past, in which collective hope reflected a national future. But I know that no such thing was possible in my environment. The only ways in which I felt that my feelings could go outward without fear or rude rebuff or searing reprisal was in writing or reading, and to me they were ways of living.”

“Mississippi’s Native Son” Symposium.

Following the founding of the Richard Wright Circle in 1990, the Richard Wright Newsletter appeared and ran for 15 years, which brought together an international community to engage deeply with the author’s work. The inaugural edition set the tone for the trajectory of the Richard Wright Circle, with a statement from Wright’s daughter, Julia Wright, and a Constitution for the Circle.

According to the Constitution, the purpose of the community was to “stimulate and promote interest in the works and ideas of Richard Wright and to facilitate scholarship and criticism on Wright’s works.” The Richard Wright Circle was open to any teacher or scholar whose work aligned with the objectives of the Circle. With an annual Wright bibliography issue prepared by Wright scholar Keneth Kinnamon, the last issue of the Richard Wright Newsletter appeared in 2006.

“The tremendous upheaval that my words had caused made me know that there lay back of them much more than I could figure out, and I resolved that in the future. I would learn the meaning of why they had beat and denounced me. The days and hours began to speak now with a clearer tongue. Each experience had a sharp meaning of its own.”

Julia Wright and Malcolm Wright at Richard Wright Centennial Event in Japan.

Credit: All photos by C.B. Claiborne except where noted.

In 2008, the U.S. Centennial of Wright’s birth was held at Natchez, MS, near Wright’s birthplace on Feb. 21, sponsored by the Natchez Cinema and Literary Celebration. The Mississippi state-wide birthday celebration was on September 4 in Jackson. A 2008 Richard Wright Centennial took place in Paris in June, sponsored by the American University of Paris and the American Embassy, which drew attendees from around the world. The Japan Black Studies Association Conference chose Richard Wright for its theme in their meeting that year at Nihon University in Tokyo.

“My reading had created a vast sense of distance between me and the world in which I lived and tried to make a living, and that sense of distancing was increasing each day. My days and nights were one long, quiet, continuously contained dream of terror, tension, and anxiety. I wondered how long I could bear it.”

Wright Centennial in Paris drew scholars from four continents.

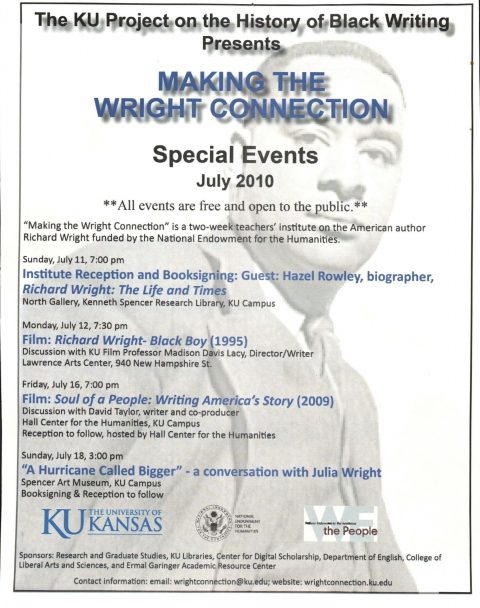

In 2010, the Project on the History of Black Writing held a summer institute for teachers, from July 11 to July 24, at the University of Kansas. “Making the Wright Connection” explored new ways to read and teach Richard Wright’s work. The fifteen-month program, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, was an extension of HBW’s professional development and public engagement work. “Making the Wright Connection” also included subsequent virtual seminars that fostered collaboration among participants and continued as an online international community for the study of Richard Wright.

Julia Wright and Jerry W. Ward, Jr.

at “Making the Wright Connection.”

Jerry W. Ward, Jr., Tougaloo College from the Introduction to 1993 edition of Black Boy:

The continuing value of Black Boy (American Hunger) is located in its providing engaging ways for us to use autobiography to think about how our lives are shaped by law and custom, by ethnic encounters andvinterracial negotiations, by desire and psychological defeat and intrepidity. The book challenges stereotypical thinking about South and North; it questions the profit of using the symbolic geographical designations loosely. In Part 1, “Southern Night” (Chapters 1-14), the autobiographical self learns that his people “grope at noon-day as in the night,” believing in a better world up North. In Part II, “The Horror and the Glory” (Chapters 15-20), Northern exposure results in the self’s “knowing that all I possessed were words and dim knowledge that my country had shown me no examples of how to live a human life” (383). There is no hiding place in regional differences. But what touches us most deeply as readers is the autobiography’s concluding words:

“I would hurl words into this darkness and wait for an echo, and if an echo sounded, no matter how faintly, I would send other words to tell, to march, to fight, to create a sense of the hunger for life that gnaws in us all, to keep alive in our hearts a sense of the inexpressibly human.”

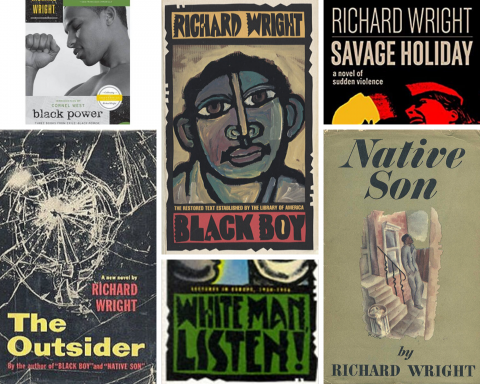

Essential Works by Richard Wright:

Graphic: HBW

- The Ethics Of Living Jim Crow: An Autobiographical Sketch (1937)

- Blueprint for Negro Literature (1937)

- Uncle Tom’s Children (1938)

- The Man Who Was Almost a Man (1939)

- Native Son (1940)

- How “Bigger” Was Born; Notes of a Native Son (1940)

- Native Son: The Biography of a Young American with Paul Green (1941)

- 12 Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States (1941)

- The Man Who Lived Underground (1942)

- Black Boy (1945)

- Introduction to Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City (1945)

- The God that Failed (1949)

- I Choose Exile (1951)

- The Outsider (1953)

- Savage Holiday (1954)

- Black Power (1954)

- The Color Curtain (1956)

- Pagan Spain (1957)

- White Man, Listen! (1957)

- The Long Dream (1958)

- Eight Men (1961)

- Lawd Today (1963)

- Letters to Joe C. Brown (1968)

- American Hunger (1977)

- Rite of Passage (1994)

- Haiku: This Other World (1998)

- A Father’s Law ( 2008)

Resources, compiled by Andi Kerbs:

“Making the Wright Connection” Summer Institute. Credit: HBW Archives

– The Organization of American Historians organized a major event hosted by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture March 29, 2008. Schomburg Director Howard Dodson, Jr. introduced the panel “Richard Wright at 100” held in the Langston Hughes Auditorium. Moderated by Maryemma Graham, the panel included poet Sonia Sanchez, Wright biographer Hazel Rowley, novelist John Edgar Wideman, and Julia Wright. Listen to discussion of Wright as fiction and non fiction writer and social critic in this video.

– Check out our various blog posts dedicated to Richard Wright’s work: HBW Blogs on Richard Wright

Recent Publications

- Anthony, Ronda C. Henry. Searching for the New Black Man: Black Masculinity and Women’s Bodies. Jackson, MS: The University Press of Mississippi, 2013.

- Gordan, Jane Anna, and Zirakzadeh, Cryus Ernesto. The Politics of Richard Wright: Perspectives on Resistance. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2018

- Hilfer, Tony. American Fiction Since 1940. New York, NY: Routledge Publishers, 2014.

- Lambert, Matthew. “’That Sonofabitch Could Cut Your Throat’: Bigger and the Black Rat in Richard Wright’s ‘Native Son.’” The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association, vol. 49, no. 1, 2016, pp. 75–92. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44134677. Accessed 25 Mar. 2020.

- Lee, Marilyn. “Richard Wright: A selectively annotated bibliography: 2004-2012” http://www.wrightconnection.dept.ku.edu/blog/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Wright-Bib-1-2-2013.pdf

- Matthews, Kadeshia L. “Black Boy No More? Violence and the Flight From Blackness in Richard Wright’s Native Son.” Modern Fiction Studies, vol. 60, no. 2, 2014, pp. 276–297. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26421721. Accessed 25 Mar. 2020.

- Phipps, Gregory. “‘He Wished That He Could Be an Idea in Their Minds’: Legal Pragmatism and the Construction of White Subjectivity in Richard Wright’s ‘Native Son.’” Texas Studies in Literature and Language, vol. 57, no. 3, 2015, pp. 325–342. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26155352. Accessed 25 Mar. 2020.

- Young, John K. “‘Quite as Human as it is Negro'”: Subpersons and Textual Property in Native Son and Black Boy.” Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850, edited by John K. Young and George Hutchinson, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 2013, pp. 67–92. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv3znzrx.7. Accessed 25 Mar. 2020.

Selected Wright Biographies

- Kinnamon, Keneth. The Emergence of Richard Wright. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1972.

- Fabre, Michel. The Unfinished Quest of Richard Wright. New York: William Morrow, 1973.

- Gayle, Addison. Richard Wright: Ordeal of a Native Son. New York: Doubleday, 1980.

- Walker, Margaret. Richard Wright: Daemonic Genius. New York: Amistad, 1988.

- Rowley, Hazel. Richard Wright: The Life and Times. New York: Henry Holt, 2001.

- Wallach, Jennifer. Richard Wright: From Black Boy to World Citizen. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010

Making the Wright Connection includes podcasts, virtual seminars, classroom resources, the Wright Newsletter Archive and bibliography supplements.