This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

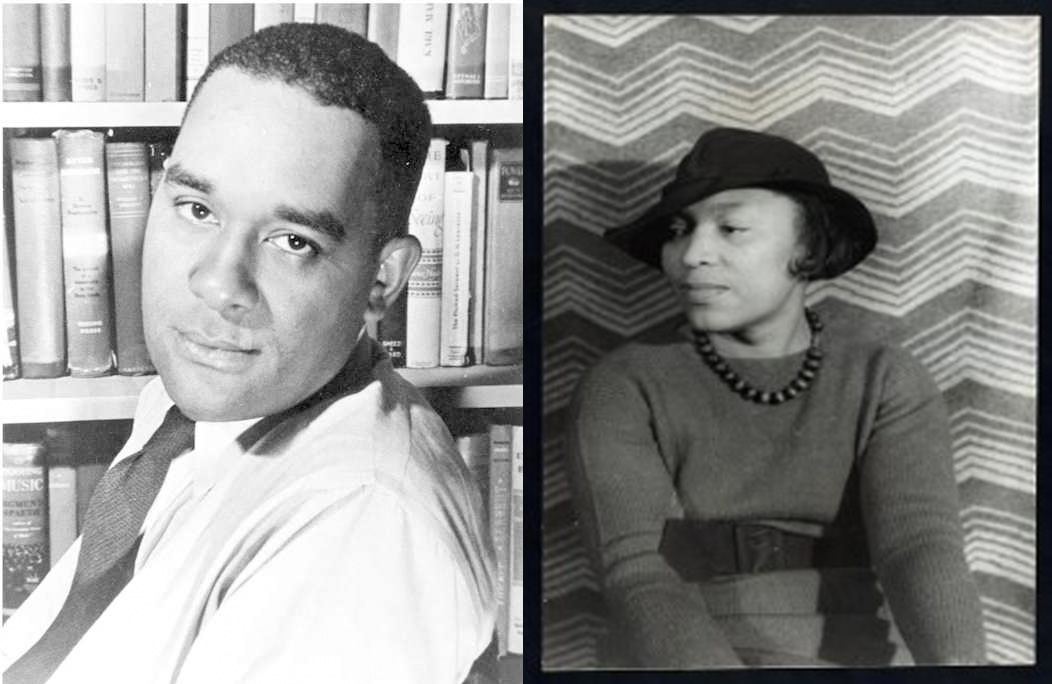

Richard Wright, Zora Neale Hurston, and Bad Blood

A (1): To read Wright’s review, click here.

A (1): To read Wright’s review, click here.

There you will find the in-house review by Hurston’s publisher and reviews by George Stevens, Lucille Thompson, Sheila Hibben, Otis Ferguson, Sterling Brown, and Alain Locke. Wright was not the only male who did not praise Hurston’s novel in 1937.

A (2): As one result of American cultural games, the bad blood has been so magnified that what is a sub-atomic particle looks like a Siberian tiger. In literary circles, one game is played by driving a contrived wedge between selected African American iconic figures. The divisive action is formulaic. Select two people —let us say, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr., Terry McMillan and Toni Morrison, or Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. DuBois. Extract diametrically opposed quotations from each either in or out of context. Magnify and distort the differences. Claim the differences are symbolic of some more or less permanent fault line in the collective consciousness of a people, symbolic of a wailing wall of hate between the two people selected. You do not have to provide proof, nor exercise the civility of waiting for an answer.

This very American game is replete with racialized ideological baggage. It is marked by bad sociology, bad psychology, and bad history. It is vicious. Fortunately, we can speculate about the bad blood between

Hurston and Wright outside the boundaries of this game as I have said in my unpublished essay “Hurston, Wright, and Literary History.” In 1937, Wright published “Between Laughter and Tears,” a combined review of Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God and Waters Turpin’s These Low Grounds in the October 5 issue of New Masses. Wright’s evaluation of both novels was less than favorable. Hurston had an opportunity to repay Wright in kind when she reviewed Uncle Tom’s Children under the title “Stories in Conflict” in the April 2, 1938 issue of Saturday Review of Literature. Hurston was less than pleased with Wright’s accomplishment.

Wright had been critical of Hurston’s sentimentality, her exploration of the human heart and love at the expense of ignoring any impact systemic racism might have had on the lives of her characters. Hurston in turn was critical of Wright’s preoccupation with race hatred, his exploitation of “the wish-fulfillment theme,” and his apparent fidelity, as she informed her audience, to “the picture of the South that the communists have been passing around of late.” Hurston was not sympathetic to the restrictions of thought implicit in Marxism American style. Wright became disillusioned with those restrictions in the early 1940s. But in 1937, Wright had no patience with Hurston’s “facile sensuality,” the structure of feelings that could be a portal to the realm of minstrelsy. The difference between the two writers is grounded in ideological opposition, incompatible ideas about the function of literature or writing in life and the obligations of the writer. Hurston and Wright had genuine reasons for concern about the effects of writing upon the minds of racially embattled readers.

Wright and Hurston were at once blunt and considerate in their attacks. They were careful in deflecting attention from personality to writing, from content of character to matters of technical skill. “Miss Hurston can write,” Richard Wright admitted. He found, however, that her dialogue “manages to catch the psychological movements of the Negro folk-mind in their simplicity but that’s as far as it goes.” Hurston did not catch the “complex simplicity” that Wright had called for in “Blueprint for Negro Writing.” That is to say, she succeed in simplicity but missed “all the complexity, the strangeness, the magic wonder of life that plays like a bright sheen over the most sordid existence….”[ Blueprint, section 6: Social Consciousness and Responsibility] Wright misread his own critical language and failed to see the sheen in Hurston’s novel. At second glance, it is not Hurston’s romanticism that he is criticizing. He is condemning her failure to link folklore with “the concepts that move and direct the forces of history today.” [Section 6]

Hurston complimented Wright by suggesting that “[s]ome of his sentences have the shocking-power of a forty-four,” a feature that confirmed for her that Wright “knows his way around among words.” Nevertheless, she found his representation of dialect to be “a puzzling thing.” How did he arrive at it? “Certainly,” she proposed, “he does not write by ear unless he is tone-deaf. But aside from the broken speech of his characters, the book contains some beautiful writing.” What was not beautiful was Wright’s male-dominated subject matter. “This is a book about hatreds. Mr. Wright,” according to Hurston, “serves notice by his title that he speaks of people in revolt, and his stories are so grim that the Dismal Swamp of race hatred must be where they live. Not one act of understanding and sympathy comes to pass in the entire work.” By way of hyperbole, Hurston found the violence of black life in Wright’s stories to be excessive. In contrast, her novel was a testament that violence and hatred in fiction should be tempered by civility, love, and compassion.

It is reasonable to propose the two reviews are gestures of respect. There is some degree of balance between the two reviews if we attend to what might have been reality for Hurston and Wright and their readers. Wright and Hurston were playing literary politics, and their discourses had to be social and political. They were writers writing about writing. Wright was conserving the radical tradition of black nationalism; Hurston was subverting the idea that a black writer had to be radical according to an “ism” that was alien to deep roots of folk wisdom. Perhaps we can avoid exaggerating bad blood and focus on how speech acts properly contextualized show that distinctions between the aesthetic and the political can be exposed as the fictions that they are.