This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

On the Relativity of Freedom in the Free State

[By: Dr. Maryemma Graham]

Toni Morrison is the greatest novelist of our times, but more and more, I find myself drawn to the wisdom in her essays, like those in Playing in the Dark or earlier works like The Site of Memory and the brutal honesty revealed in “Unspeakable Things Unspoken.” The Origin of Others is her latest testament to the truth of our time, reaffirming her unique ability to read the current moment and to respond appropriately to it. It is for that reason that I turned to Morrison recently in an effort to understand what it means when the concept of the “other” begins to center our being, when we become strangers to one another, forced into formulaic behaviors and actions at the hands of aggressive, insensitive leaders, whether in our national politics, international relations, or bringing it closer to home, on a university campus in the 21stcentury.

I live and work in what was once regarded highly as the “Free State,” where that mini-civil war known as Bleeding Kansas foreshadowed the intense debates making a marriage of ethics and politics. In the end, two geographically connected states, Missouri and Kansas, became deeply divided over the issue of slavery. Kansas did not follow Missouri, its neighbor’s example, and entered the union as a state without slavery. Today, John Brown’s courageous challenge to the system of slavery is memorialized in a state house mural. Kansas artist John Steuart Curry’s rendering of that remarkable event sends a message that has been passed down through the ages. Freedom from oppression, the founding principle that gave birth to what became our part of the Americas, united a nation as much as it tore it asunder. That the mural remains in the capital tells us that we Kansans take our free state status seriously, or at least we did at one time.

There is a long tradition of that in Kansas: the use of artistic expression to broaden knowledge. When Kansas has forgotten its own roots, art has helped to sustain, if not reclaim it. Langston Hughes who wrote his autobiographical novel Not Without Laughter about his childhood in Lawrence, once dubbed his school experience the “Jim Crow Row.” In “Merry Go Round,” Hughes elaborates on the concept that became a national symbol of segregation. In 1954, the Brown family joined other families challenging the segregated school system in Topeka in a case that went all the way to the Supreme Court. Known familiarly as the Brown Decision, school segregation was abolished – in theory.

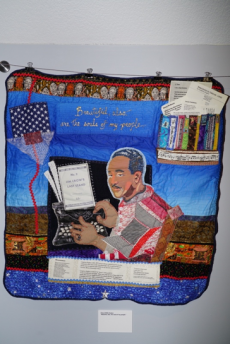

Langston Hughes’ work has continued to serve as inspiration for artists on Kansas soil. Cheryl Willis Hudson, for example, is one of many quilt artists building on the Jim Crow theme, now on exhibit as part of the 2018 National African American Quilt Convention.

Kansas native Gordon Parks, who spent his early years in Ft. Scott, experienced the harshness of rural poverty, but took from it the inspiration for his life’s work as a photographer. Showing America itself through the camera’s eye, Parks earned his stripes with timeless classics like American Gothic. While working for the photography unit of the Farm Security Administration, Parks met Ella Watson. In the legendary photograph, we see Ella Watson’s image in stark relief against the American flag, a foremost symbol of “land of the free.” Watson’s story was brutal: her father had been murdered by a lynch mob and her husband shot to death. Fully aware of Grant Wood’s 1930s painting by the same name, Parks felt compelled to point the sharp contrast to Woods’ image of classic America. His photograph captured the reality of Watson’s life that was not easily reconciled with the land of the free. Parks, like Hughes, would also use his Kansas childhood as the basis for an autographical novel, The Learning Tree. In a most unusual move, when the book was optioned for a film, Parks convinced his Hollywood backers to film on location in the very place where his story had begun. In 1968, the film crew, actors, and the Ft. Scott community learned their own lessons in a desegregated Ft Scott, which served as the backdrop for the fictional “Cherokee Flats,” of Parks’ childhood.

One does not have to dig very far into Kansas history to discover the pull the free state had for untold numbers who came as pioneers, homesteaders, and after Emancipation, as newly freed people, all in search of a new life. They came, even though for many that freedom did not match the reality of their subsequent experience. Author and educator, Carmaletta Williams puts it well, “free did not mean welcome,” she explains in her family’s story of migration to Kansas in mid-1879 as part of the Exoduster Movement lead by Pap Singleton. “Those freed folks escaping a neo-slavery in Tennessee came to Kansas believing in the promise implied in the appellation ‘free state.’”

It is most unfortunate that a legacy so vital to the state’s history and shaping its culture means nothing to our state leaders, especially our Governor, who poses the greatest threat to the free state in our own time. Josephine Meckseper’s contribution to the “Pledges of Allegiance” exhibit at KU was a defamation of the American flag, he declared, giving the most rabidly conservative wing of our citizenry and state leadership free license to create a climate of fear.

To demand the abrupt removal of the work is wholly un-American and anti-democratic, contradicting the idea of America itself. The same people who were adamant in their support of the second amendment have shown a total disregard for the rights guaranteed in the first amendment—the freedom of speech, and by implication, freedom of artistic expression. By complying with the demand KU Chancellor Girod became complicit in these authoritarian acts. These are shocking reminders of who we are and what we are not in 2018. Clarity is needed in a time of radical ignorance – when distortion of facts and anti-intellectualism reign supreme. If the university places so little value on freedom of expression, then it is no longer what we need or expect it to be.

But let us remind ourselves once more that we are what we do. It was the free state legacy –along with the second amendment – that enabled a backward step for Kansas in 2017. On July 1, it became legal to carry a concealed gun on our campus and inside our classroom buildings and residence halls. That single act presents a serious challenge for anyone who believes in education as a place for debate and dialogue. Expectations of expanding one’s vision of the world and of finding a place within it are all but destroyed, as knowledge, art and the imagination become derivative. The protections against the suppression of information that anchors human understanding disappear. Instead, the state’s governing body is promoting a learning environment driven by fear. As a human emotion, fear can drive actions that are deadly. We know that history all too well.

It is that same spirit of fear and repression that Meckseper’s work has become embroiled. We are now in the aftermath of the controversy, seeking redress. I use this word intentionally because it tells us exactly what we must do: right the wrong that was done by removal of an art work that fits into a long tradition of peaceful protest in our nation.

In running roughshod over the first amendment – we failed to center ourselves in that tradition, our legacy as a free state, and worse, in the accumulated knowledge that we represent as a community of scholars and educators. Why was it so easy for us to disconnect from history and the historical process, from a social, cultural and political heritage rooted in resistance to oppression?

I am troubled by our lack of preparedness during the height of the controversy and now, as we seek to ban together as a community. What knowledge are we bringing to the table? None of what we experienced is new, that is, attempts at a takeover by those who fear public debate and dialogue, and realizing knowledge is power, use bullying tactics to render us silent.

For starters, we might look at that longer history of the American flag, the foremost symbol of political freedom. We might have our Law school professors review the controversy and court cases over burning the American flag in 1989-90- during the Bush years – a Republican era no less. There were heated debates, but the courts upheld the first amendment, ruling that “tolerating flag desecration is hardly likely to threaten its symbolic value …. [and] forbidding flag burning as a means of peaceful political protest will diminish the flag’s symbolic ability to represent political freedom.” (Robert Goldstein, “Burning the Flag 1989-The American Flag Desecration Controversy”).

In sum, this is not a case of blindness, but fear born out of sheer ignorance, a failure of leadership and of our knowledge community. While we brought a heartfelt response to the removal of the art work and offered a solution for relocation, we have yet to put forth a concerted effort to do the necessary intellectual work and engage directly with our rights and responsibilities. Continued neglect on our part will dig an even deeper hole, so that the practice of freedom as a guiding light will be diminished.

We have to agree with Goldstein’s conclusion about that earlier period in the debate over the U.S. flag — that something like a flag controversy could only exist when there is a failure to address the country’s real problems. Such failures easily foster a climate of uncertainty that allows less significant matters to occupy so much space. For us as a university community, it requires us to teach harder and smarter.

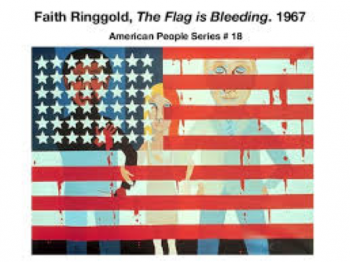

To help revitalize our mission, I recommend bell hooks’s Teaching to Transgress: Education as a Practice of Freedom. Teaching harder and smarter means that we must have those difficult dialogues, and that we let Meckseper’s art lead us to a longer history of art and cultural expression that knocks us out of our historical and social anesthesia. Let’s leave the fluff behind, avoiding short term solutions that stop short of a strong resistance to those attacks on the basic tenets of democracy. We might also revisit the trigger word that stands out in the governor’s critique, “defacement.” If we read its Latin root, prefix and suffix, to deface something is to remove, to bring something different into existence, to separate. In short, going beyond the surface, we can bring a deeper truth into existence. Meckseper understands what Gordon Parks did in photographing American Gothic and what Faith Ringgold does in her series of interpretive flag quilts. As Ringgold noted in her talk at the Spencer Museum, happening at the same time Meckseper’s work was being removed, freedom of expression is essential to the visual artist, if she is to speak her truth, bringing a hidden reality into plain sight.

To help revitalize our mission, I recommend bell hooks’s Teaching to Transgress: Education as a Practice of Freedom. Teaching harder and smarter means that we must have those difficult dialogues, and that we let Meckseper’s art lead us to a longer history of art and cultural expression that knocks us out of our historical and social anesthesia. Let’s leave the fluff behind, avoiding short term solutions that stop short of a strong resistance to those attacks on the basic tenets of democracy. We might also revisit the trigger word that stands out in the governor’s critique, “defacement.” If we read its Latin root, prefix and suffix, to deface something is to remove, to bring something different into existence, to separate. In short, going beyond the surface, we can bring a deeper truth into existence. Meckseper understands what Gordon Parks did in photographing American Gothic and what Faith Ringgold does in her series of interpretive flag quilts. As Ringgold noted in her talk at the Spencer Museum, happening at the same time Meckseper’s work was being removed, freedom of expression is essential to the visual artist, if she is to speak her truth, bringing a hidden reality into plain sight.

In 2018, the nation is indeed more divided more than ever by race, class, and color, and we need to be reminded of that time and time again. Becoming immune to this reality, bowing to the demands of politics insults all of us, devaluing everything we do as educators, scholars, and artists and the students who seek to expand their knowledge and ideas of social justice. In her conclusion to “Being or Becoming the Stranger,” Morrison cautions us against sentimentalizing, forgetting “the power of embedded images and stylish language to seduce … control.” She urges us to “remain human and block the dehumanization and estrangement of others.” Josephine Meckseper became the other, the larger impact of her work as a public statement diminished. Her accusers feared that her art would do what good art informed by social justice always does: challenge our sensibilities, resist our acceptance of the ordinary, and force us to admit difficult truths.

If we continue to comply to such requests by the governor, we obliterate all the hard work of our forefathers and mothers who created Kansas as a free state. We cast education aside and find ourselves reversing the decisions made when Kansas was “Bleeding.” Rather than resisting, we become enslaved to new practices that undermine the basic tenets of democracy. And this is the kind of slavery that will be an equal opportunity employer.

Dr. Maryemma Graham is the Founder/Director of the Project on the History of Black Writing and Distinguished Professor of English at the University of Kansas.