This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

Reading Sterling D. Plumpp

NOTE TO READERS:

NOTE TO READERS:

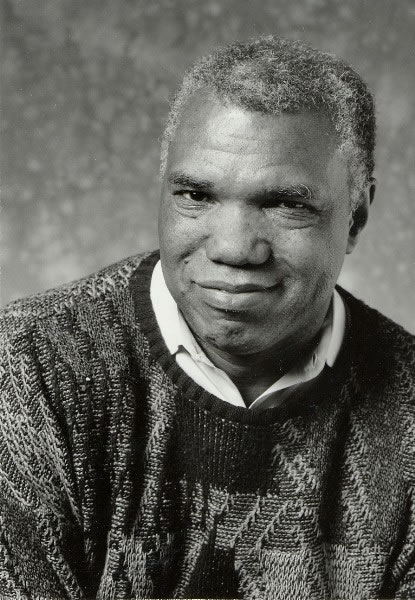

In March 1995 I spoke about Sterling Plumpp in the PASSWORDS series at Poets House, proud to be a Mississippian in New York speaking about a

In March 1995 I spoke about Sterling Plumpp in the PASSWORDS series at Poets House, proud to be a Mississippian in New York speaking about a

Mississippian. Poets House was then located at 72 Spring Street. It is now located at 10 River Terrace. In 1995, I thought Plumpp was the finest blues poet our nation had produced, surpassed only by Langston Hughes. Much has changed. In 2013, I am convinced Plumpp is still standing next to Hughes; no writer who claims to be a blues/jazz poet surpasses him with the exception of Amiri Baraka, who is our most total music poet. Should I discover that anyone agrees with my opinion, I shall promptly have a minor heart attack. That person will have killed my ability to have the blues.

I venture into the future to find the present and leave the past frozen. Obviously, I am troubled by the apostasy that infects our contemporary discussions of poetry. I will learn you to play bid whist with Death. If you choose, you may turn ice into either steam or water. It is entirely up to you.

THE TEXT:

One poet looks at another. He watches him coming through and out of chaos, out of Mississippi —the blood, sweat, mud and terrors of the near past, coming out of Clinton, MS –a hoot and a holler down the road from the Delta, the womb of the blues. Watches him follow that smokestack lightning, up the tracks the train will take to sweet home Chicago, Mecca, Chi-town, the promised land. Watches too the proverbial progress from the frying pan to chaos to the skillet, the jump from bad to bad in the territory where one sings the blues, or constructs a sensibility, an aesthetic, a whole body of work from Portable Soul (1969) to Hornman (1995)

Intervention at 12:32 a.m. —For commentary on Plumpp and his post-1995 books — Ornate With Smoke (1997), Blues Narrative (1999), and Velvet Bebop Kente Cloth (2001), read Valley Voices 9.1 (2009), edited by Hermine Pinson and Duriel E. Harris. The deep pleasure of remembering that Plumpp, Keropetse Kgositsile , and I listened to Fred Anderson playing horn and Duriel Harris reading her poetry at the Velvet Lounge (Chicago) in 2001; that Lorenzo Thomas, Plumpp and I had to do some serious learning when Junior Wells sang somewhere at sometime.

One poet worries out the meaning of the other poet’s dark journey from peasant origins to achievement by dint of pure will, mastery of craft and the particularity of speech and music as referents that mark the contours and qualities of the new black [American] poetry (Stephen Henderson’s theory), by continual autobiographical exploration of the ethos of the blues until the other poet strikes a massive vein of gold in the rockbed, only to reveal that there under everything is a diamond in his African ancestry.

The poet from Clinton, who now claims and is claimed by Chicago, is Sterling Dominic Plumpp. It is his work I celebrate, not by lecture but by a collage of sound — an effort to freeze patterns of meaning in his work. For he is the best blues poet of my generation (alongside the blues musicians who are poets) driven to an awakening by Johannesburg and the possibilities of finding the majesty of the blues in jazz.

In his first book, Portable Soul(1969), Plumpp’s poems conform most to an urban mode or to the UpSouth idioms of the 1960s/1970s to be found in much black poetry, that reformation of language which threatened to render all of the collective voices, in the worst instances, not distinguishable from one another. If you did not know how to pay attention to context clues, you might mistake a poem by Plumpp for a poem by Don Lee (Haki Madhubuti) — so strong was the OBAC/Chicago sound issuing from the workshops as the seeds of the Black Aesthetic began to assume shape. But the blues in Plumpp came through in the poem entitled “Black Resurrection” (Portable Soul 18).

Three deep blues features in this poem deserve special attention. First, there are the compressed images of blues origin ( murmur of chains/ chords of my captivity) which evoke a cause-effect relation between historical experience and musical expression. The surreal, gripping image of “tears hanging / down into the waiting grave” strike a tonal memory of the blues as “crying songs of laughter.” The crossing of the sacred and the secular where the specific song titles are the communion bread and wine (Roman Catholic rite) is a counter-gesture to the usual careful distinction kept between the godly and the ungodly among blues people.

So the blues was a way out of the dilemma of craft for Plumpp. Not to write in the fashionable style, but (like some early 20th century Harlem Renaissance poets) to mine what had always authenticated Black Art, namely according to Plumpp in his essays on psychology (Black Rituals 1972), the Blues, Spirituals, and the Black Church. Even if one rejects the so-called intentional fallacy in interpretation, it does not hurt to know that Plumpp was working through an ideological/technical crisis that put him in some opposition to the poetic outpourings of cultural nationalism. Plumpp has intentions.

So the blues was a way out of the dilemma of craft for Plumpp. Not to write in the fashionable style, but (like some early 20th century Harlem Renaissance poets) to mine what had always authenticated Black Art, namely according to Plumpp in his essays on psychology (Black Rituals 1972), the Blues, Spirituals, and the Black Church. Even if one rejects the so-called intentional fallacy in interpretation, it does not hurt to know that Plumpp was working through an ideological/technical crisis that put him in some opposition to the poetic outpourings of cultural nationalism. Plumpp has intentions.

Listen to this: “Another misunderstanding concerns the Blues. People who sing the Blues are reflecting a worldview that is particularly Black. They have not resigned to accept their fate but have found ways to admit to themselves and their brethren their troubles. I don’t think this necessitates a dichotomy with Blackness” (Black Rituals 71).

So Plumpp would opt for the blues basics of his origins in Mississippi. The option does not bespeak raw imitation of blues structure but sophisticated use of blues substructures, the multi-leveled feelings behind the class AAB stanza and it variations. Yes, Plumpp could do that. Two demonstrations. Listen to the version of his poem “Son of the Blues” recorded by SOB/Chitown Hustlers [ Billy Branch and Sons of Blues, Where’s My Money?( Red Beans RB 004)] and then read/juxtapose “Worst Than the Blues My Daddy Had” which was published in the 1993 collection Johannesburg and Other Poems, pages 10-11. Both poems come from the 1982/83 manuscript entitled “Worst Than the Blues My Daddy Had.” But the bulk of the poems written in this style are not published. There was a watershed moment in Plumpp’s understanding of what he was doing as a poet. Referring to such poems in notes appended to the manuscript, Plumpp claimed

The individual blues piece, Blues Song-Poems as I call them, are direct referents to a wide variety of feelings, emotions, concern, attitudes, and situations which confront on three levels: as an individual, as a member of the Afro-American national group, and as a member of the human world threaten [ed] with extinction because so few men hold the power to destroy. For me, they broaden the range of my voice and bring into focus elements of concern submerged: irony, lightheartedness, empathy with females, and a deep preoccupation with the sensual.

……

They are pieces reaching to the largest possible audience since aside from the blues form (AAB) they deal with situations real people find themselves in and they don’t pose any easy solutions.

…..

The blues poet writes so his lines are lyrical yet song as read; they do not depend upon a performance for their effect. The temptation to condense and edit out the raw oral quality of blues poems will only amputate their authenticity; for blues are feelings at their most unexpurgated level.

Are we quite certain that blues effects do not depend upon a performance? Make a test. Listen to the bluesman Willie Kent sing Plumpp’s poem “911.”[Too Hurt to Cry. Delmark DE 667] Kent’s vocal interpretation convinces me that performance makes all the difference.

On May 20, 1983, I wrote to Plumpp:

Sterling, I feel the poems that are identified as blues songs are too conscious of the formal properties of blues –you let repetition and the impulse to rhyme dominate feeling, the heartbeat and muscle of the blues.

In making your blues song-poems you are too aware of yourself as a poet, too little inside your feelings or the feelings you assign to the persona in the poems. Remember Ellison’ saying the blues are about running one’s finger over the jagged edge of life? Well, after you cut your finger, you suck the poison out, wrap the wound in a cobweb, and keep on moving. If the blues was about staying with the pain, the jooks would be empty on Saturday night.

Sterling’s revenge was to dedicate the poem I said was the best example of a Sterling Plumpp blues, “Muddy Waters,” to me in Blues: The Story Always Untold.

Intervention at 1:57 a.m. My letter to Plumpp was written after reading and discussing Plumpp’s manuscript with the young poet Charlie Braxton.

A historian might connect Mississippi and South Africa through comparative study of systems of oppressions. Plumpp connects those sites of humanity and experience by responding to a historical call in “Thaba Nchu” (Johannesburg and other Poems 107) When a special collection of signature poems by twenty-three poets was printed in September 1994 for the “Furious Flower: A revolution in African American Poetry” conference (James Madison University), “Thaba Nchu” was Plumpp’s contribution. This poem may be a new writing of his name, a poetic completion of the search for temporal location (not to be confused with

search for roots) which is initiated in early poems in the volumes Portable Soul and HalfBlack, Half Blacker and in a telling stanza in the long poem Steps to Break the Circle (1974):

My Black Man’s days are epic curtains

Drawn shades of my light moments

Pyramidal drapes of red, green and black

Shaking their round asses to the beat

Of a tom-tom and conked conga

Falling dreams sliding down

To ponderous claps of wonder

And a predictive closure

My feetsounds is thunder blows

I shango I shango shango shango

Shango down the freedom road…

a return to the ancestral homeland of theNew

World blues. The circle can only be

broken

by taking the steps to reestablish the

circle of African authenticity in

which

the African gods are active verbs,

because

anyone who dares to transform

the

name of a god into a verb certainly would have to go where the

mojo

hands called. (25)

From the collection The Mojo Hands Call, I Must Go (1982), which won the 1983 Carl Sandburg Award for Poetry, your reading of the stunning “I Hear the Shuffle of the People’s Feet” (35-42) can perform the verbalizing of a god. When Plumpp started talking on the autobiographical highway of Clinton (1976), he told you everything you must know until you arrived at Johannesburg & Other Poems (1993) and heard Hornman (1995). In his early poems and in Blues: The Story Always Untold (1989), Plumpp had played the totality of the blues, inscribing the urgency of refiguring his Mississippi self in relation to Africa by way of the rituals, social performances, and folkways urbanized in Chicago. He mapped the territory in sentiments and forms. He was a native son of the blues, sending its light through the Chicago prism of his imagination until….until Hornman celebrated the saxophonist Von Freeman and took us and him into a jazz end zone.

Jazz appropriation does not mean Plumpp has abandoned the blues. No. The man has gone deeper. Through the prism of his acute sense of where he came from and who he is, Plumpp has made poetry an instrument of consciousness. At the crossroad of blues and jazz, reading Plumpp’s poetry is an act of metamorphosis, one poet talking to another in the university of a blues club.