Reading Kevin Powell’s Education

Autobiography is one of the more intriguing mixed genres of American writing. Elizabeth Bruss’ Autobiographical Acts: The Changing Situation of a Literary Genre (1976) may lead us to believe that the “rules” governing autobiography are stricter than those which pertain to drama, poetry, and fiction; awareness that generic “rules” are based on abstractions from histories of reading, however, invite us to amend them in our acts of interpretation, in the acts we commit in order to grasp the meaning of texts. We are willing to break them. We allow the writer of autobiography great latitude in arranging language and rhetorical devices in her or his effort to bear witness to “a truth, ” because we associate the truth of what happened with the individual’s confessional, psychological ego-investments. Adjustments, exaggerations, forgetting and remembering, and selective displacements are in motion as part of the shared authority of the writer and the reader. Our own egos and needs are implicated in judgments about what is true or false. So too are our ideas about collective features of life histories. What social and cultural conditions are the powerful motives in the act of writing? What counts most in our reading and interpretation of autobiography, perhaps, is the sense that the narrator as well as the persona who stands in for a Self are reliable. We demand, in most cases, assurances that the autobiography is more than an absurd, commercial gimmick or a game of linguistic wilding. If the assurances fail, we are not devastated. We all understand how American citizens “play” one another. These considerations allow us to have a rich transaction with The Education of Kevin Powell.

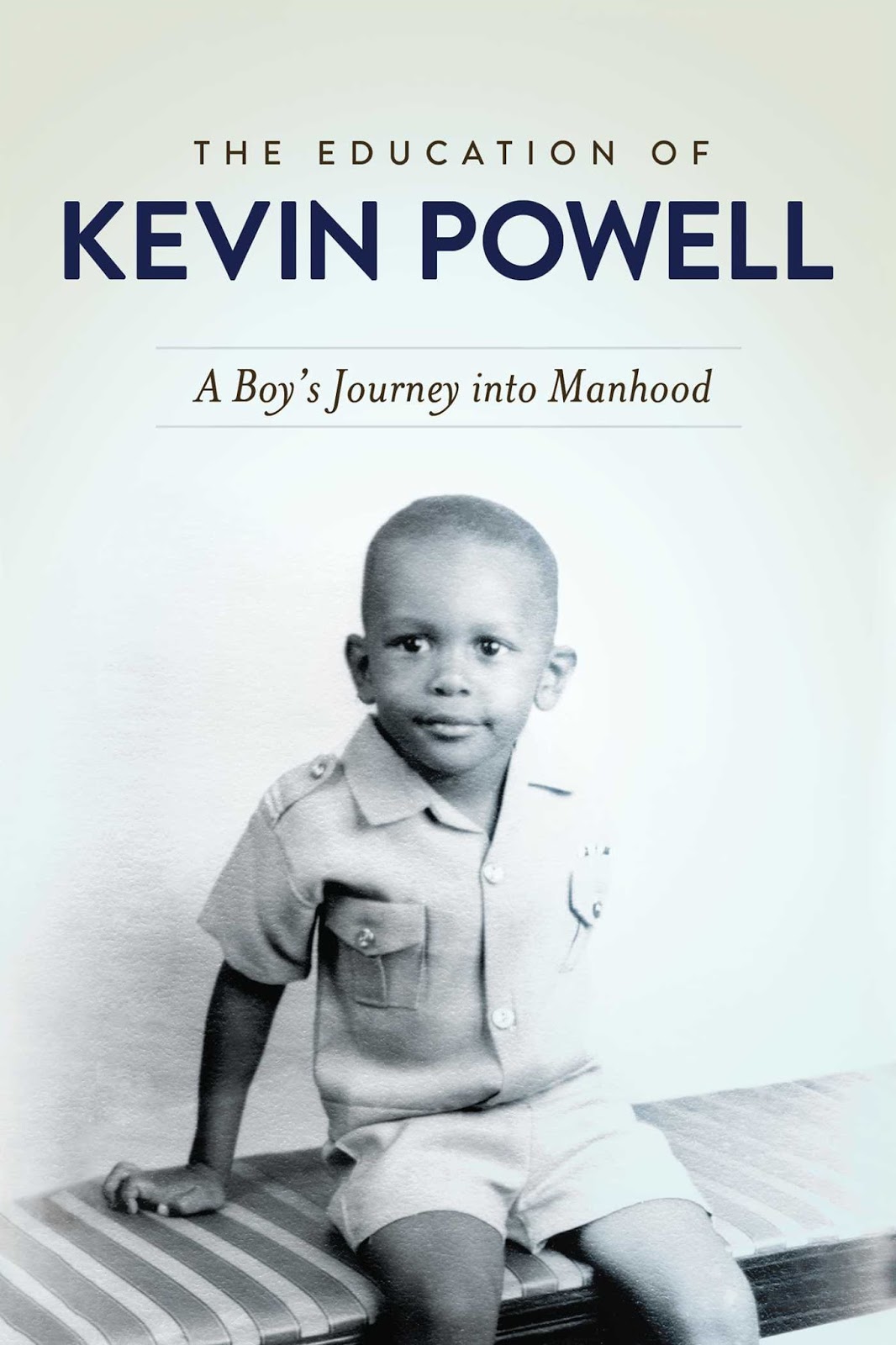

Even before we begin to read Powell’s autobiography, we may be given pause by his strategic choice of a title. The Education of Kevin Powell echoes the title of an older, privileged, and seldom read autobiography, namely The Education of Henry Adams. Perhaps the choice was not merely accidental. Perhaps the twenty-first century Kevin Powell actually wanted to expose the vast and crucial differences between his journey and the one taken by the elitist nineteenth-century descendant of two American presidents. To imitate a well-known metaphor from Booker T. Washington’s autobiography, we can say that as writers Powell and Adams are connected in a literary enterprise; as American citizens, they as separate from one another as the little finger is from the thumb. The exact circumstances of Powell’s choice are, and should remain, a tantalizing mystery. It suffices that The Education of Kevin Powell is a magnificent deconstruction of the fiction named the “American Dream.” Powell’s autobiography or memoir is a trenchant disrupting of the enabling grounds that inform The Education of Henry Adams. Thus, Powell secures his niche in the tradition of American autobiography by maximizing the oppositional potency of the African American autobiographical tradition, the telling a free story about what is universally recognized as unfreedom. And we ought not minimize the fact that Powell gives us both subjective and objective evidence of his character and courage through writing as an act of brutal honesty.

It may be apparent to discerning readers that The Education of Kevin Powell is a gendered, medium-crossing, asymmetrical companion to The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (Ruffhouse Records CK69035), a musical witness that conjures Carter G. Woodson’s The Miseducation of the Negro (1934). Other readers may think of The Education of Sonny Carson (1972) and the 1974 film of the same title, of the education that is actually located in the mean streets of our nation rather than in its “celebrated” institutions of public schooling and higher learning. The value of such associations is to highlight what an American education outside the questionable “safe” zones of formal institutions really is.

Focusing on American education prevents an automatic reading of Powell’s book as yet another African American saga of abject disadvantage and noble struggle to transcend. His writing pertains more to flight into than flight from something. By way of learning-oriented approaches to his text, we might discover what that something might be and why we need to be better informed about it than most of us are. Giving priority to our education as readers frustrates the banal tendency to stereotype American and African American autobiographies as stories of radicalization and identity politics and racialization. An unorthodox reading of The Education of Kevin Powell can expose how phony is a tearful and self-serving reception of the book. Reading against the grain reduces indulgence in the delusion and bad faith of pity. It liberates us to grasp how raw will power enables an American male to prevail in the endless, uneven, traumatic attempt to reach the telos of being human, of being a good citizen in a chaotic universe.

Powell’s autobiography makes a strong case for the power of the will. He reinforces the idea of responsible agency which is central in the essays he collected and edited in The Black Male Handbook (2008) and in his own essays in Who’s Gonna Take the Weight?: Manhood, Race and Power in America (2003) and Someday We’ll All Be Free (2006). Indeed, we can learn from this autobiography what the American entertainment/ disinformation industry wants us not to know about the essence of being hip-hop or the transformational complexity of oppositional stances. Powell exposes the education America imposes upon it male citizens.

This autobiography has two parts. Part 1 “trapped in a concrete box” contains seventeen chapters which deal with the spatial origins of Powell’s long, unfinished journey; the thirteen chapters of Part 2 “living on the other side of midnight” give specificity to the temporal, to the events and people in the unique trajectory of Powell’s life to the present. The introduction establishes the dominant image of violence and being beaten, the image that haunts us frequently in the autobiography and in our everyday lives. Powell’s words “the beating as punishment for my life” operate in unsettling concert with the line “trapped in a concrete box” from his poem “Mental Terrorism” in Recognize (1995) and his plain assertion that “writing is perhaps the most courageous thing I’ve ever done.” Through writing Powell instructs us time and again that “there is something grotesquely wrong with a society where millions of people face daily political, cultural, spiritual, psychological, and economic oppression by virtue of their skin complexion.” His recognition of what is at once explicit and implicit in an American education justifies his desire to have writing “open up minds, feed souls, bridge gaps, provoke heated exchanges” and authorizes a yearning, present throughout world history, to have writing “breathe and live forever.” Without saying so directly, Powell challenges Allan Bloom’s famous lamentations in The Closing of the American Mind (1987), and subverts Bloom’s complaint by writing to open the imagined mind of the United States of America.

Critics who cohabitate with aesthetics have no reason to fear that Kevin Powell minimizes craft in contributing to the production of knowledge, because he is appropriately literary in shaping autobiography. The title of his book is a very literary gesture, a discriminating invitation to use uncommon cultural literacy about the nature of American autobiography. He is even more recognizably literary in using the device of the catalog of discoveries (as Richard Wright used it in Black Boy) to hammer ideas about the journey from boyhood to manhood —–“like the rupture…like the longing…like the bewilderment…like the hostile paranoia…like the cryptic sense of great expectations.” And the latter allusion is one result of Powell’s having read both Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Dickens in his youth. Powell’s anaphoric use of “I remember…I remember…I remember” attests to how he inserts his poetic sensibility to serve the rhetorical ends of creative non-fiction. And it is remarkable that he rewrites a passage from Black Boy about how adults use alcohol and words to “corrupt” a child for their careless amusement to dramatize an educational moment.

Like Wright, Powell uses what purports to be remembered dialogue to intensify our sense of the affective properties of historiography and to suggest historical process always comes back to us as narrative not as objective reporting that is in denial of its inherent subjectivity. Powell is crafty and exceptionally skilled in creating literature that does not hesitate to critique the limits of moral imagination. Or, for that matter, the innate immorality of twenty-first century societies, and those wretched circumstances, so permanent in our heritage of social and racial contracts, which cast light on the moral dimensions of his profound struggles with his own sexism and his anger, his male American identity.

The Education of Kevin Powell and Ta-nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me are indebted to Wright and to The Autobiography of Malcolm X, a fact that legitimizes comparison. But the comparison ought to be tough-minded and should make a special note that Coates and Powell are writing from different but convergent class positions. Interpretive association of Coates with Benjamin Franklin and of Powell with Henry Adams enables us to have fresh perspectives on representing privilege, race, and power without falling into merely tendentious literary and cultural criticism or drowning in lakes of fickle public opinions. But we must remember that an understanding of these autobiographical writings also imposes upon us the need to assess what we know or do not know about our own existential choices which pertain to leadership and activism. The books complement each other as we try to make sense of individual plasticity in human response to Nature and multiple environments. Reading both compelled me to make a choice. I admit that the vernacular qualities of The Education of Kevin Powell instruct me more thoroughly about the genre of autobiography. His writing encourages me to learn more about aligning the building of knowledge for everyday use with critical aesthetic response.