This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

Reading the dystopia wherein you live (revisited)

Categories: HBW

Since January 20, 2017, it is quite fashionable to talk about Donald J. Trump under the influence of reading dystopian or apocalyptic fictions. There is the possibility that what fifty years ago was accepted as “the news” is now a blatant form of social fiction. Broadcast from every ideological angle, what seems to be the news is replete with alternative facts and unacknowledged projections of imagination. There is a thin line between description of actuality and its reception in various media. And many readers hop across the line without benefit of thought. Reading is simply automatic, a reflex action.

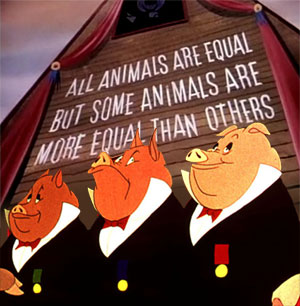

A few of us who stay out of touch with reality believe genre distinctions matter, and we attempt to discriminate such dystopian novels as Ishmael Reed’s The Free-Lance Pallbearers and George Orwell’s Animal Farm from tomorrow’s news that happened yesterday. Our reading is a mission impossible. We are the news. That is to say, we inhabit the dystopia we’d like to claim is external to us.

A few of us who stay out of touch with reality believe genre distinctions matter, and we attempt to discriminate such dystopian novels as Ishmael Reed’s The Free-Lance Pallbearers and George Orwell’s Animal Farm from tomorrow’s news that happened yesterday. Our reading is a mission impossible. We are the news. That is to say, we inhabit the dystopia we’d like to claim is external to us.

The problem seems to defy resolution. We can, however, take pragmatic measures to minimize its paralyzing effects. We can segregate dystopian fictions from descriptive treatises by using traditional conventions of reading. The treatise purports to be objective and explanatory. The fiction is a subjective guide for analysis and interpretation. We gain a bit of comfort from thinking we know the critical difference between fiction and nonfiction. Perhaps we do not, for we are characters in a “great” novel entitled Acirema the Great.

Acirema the Great opens with cheers of victory on 11/9. One disgruntled character mumbles that for the first time since Thomas Jefferson, a real President, died in 1826 and walked into American mythology —the comfort zone occupied by every President until 2016, voters are being asked to make sense of a fake President who has tweeted himself out of mythology into actuality. Does the signifying monkey speak his mind about pravda? The nameless character opens John Gardner’s On Moral Fiction (New York: Barnes & Noble, 2009) and reads the chapters on moral fiction and moral criticism.

Acirema the Great opens with cheers of victory on 11/9. One disgruntled character mumbles that for the first time since Thomas Jefferson, a real President, died in 1826 and walked into American mythology —the comfort zone occupied by every President until 2016, voters are being asked to make sense of a fake President who has tweeted himself out of mythology into actuality. Does the signifying monkey speak his mind about pravda? The nameless character opens John Gardner’s On Moral Fiction (New York: Barnes & Noble, 2009) and reads the chapters on moral fiction and moral criticism.

He hits the motherboard. Gardner proposed “that scrutiny of how people act and speak, why people feel precisely the things they do…lead to knowledge, sensitivity, and compassion. In fiction we stand back, weigh things as we do not have time to do in life; and the effect of great fiction is to temper real experience, modify prejudice, humanize” (105). Aha. A fake President is a great fiction, one who tweets that every noun is “great.” A cartoon of real experience, Trump donates the gift of moral education to the American public. If Gardner is to be believed, writers stand a better chance than do non-writers of knowing to what extent Trump is an unreliable facsimile. Do ordinary citizens have to become writers to arm themselves for political action? Do they have to write themselves out of slavery into freedom, out of the caves of Greek philosophy into the warmth of other suns?

A fake President is a liability, a politically reprehensible liability. The whole world knows that, and the terrorists among us treat the false truth as a matter of fact. Regardless of their political beliefs, American citizens agree that a fake President is a work of art, a moral fiction. And they are condemned, the disgruntled character remarks to treat Gardner’s conclusion about moral criticism with grains of pepper and doubt. “It is precisely because art affirms values,” Gardner asserted, “that it is important. The trouble with our present criticism is that criticism is, for the most part, not important. It treats the only true magic in the world as though it were done with wires” (135). Really? Isn’t the only true magic in the world done with computers?

A fake President is a liability, a politically reprehensible liability. The whole world knows that, and the terrorists among us treat the false truth as a matter of fact. Regardless of their political beliefs, American citizens agree that a fake President is a work of art, a moral fiction. And they are condemned, the disgruntled character remarks to treat Gardner’s conclusion about moral criticism with grains of pepper and doubt. “It is precisely because art affirms values,” Gardner asserted, “that it is important. The trouble with our present criticism is that criticism is, for the most part, not important. It treats the only true magic in the world as though it were done with wires” (135). Really? Isn’t the only true magic in the world done with computers?

Thus, the insertion of Trump within the act of reading Animal Farm or The Free-Lance Pallbearers involves one major error. We fail to account for the great agency of citizens, readers and non-readers alike, who use a fake President as the heroic symbol of their lesser selves. We should try to avoid the error as much as we can. And if we do want to be effective in saving democracy from drowning in fascism, we may want to permit the fake President to have the absolute right to commit treason with immunity from impeachment inside and only inside Acirema the Great.

Reginald Martin’s remark about Reed’s The Free-Lance Pallbearers in Ishmael Reed and the New Black Aesthetic Critics (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988) invites us to be cautious: “the contemporary indices [here the reference is 1967]in the course of the novel certainly changed the reference points of American novels up to that time”(42).

Reginald Martin’s remark about Reed’s The Free-Lance Pallbearers in Ishmael Reed and the New Black Aesthetic Critics (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988) invites us to be cautious: “the contemporary indices [here the reference is 1967]in the course of the novel certainly changed the reference points of American novels up to that time”(42).

Fifty years later, the indices Reed rendered as fiction are still recognizable and operative in the dystopia of American political economy. All changes. All remains the same.

We must use prudent skepticism as we critique how our fellow Americans act and speak, how they broadcast the news in the great and brave new world that was born on November 9, 2016. Above all, we must vote and force real politicians to represent real human beings not characters in dystopian or apocalyptic fictions.