This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

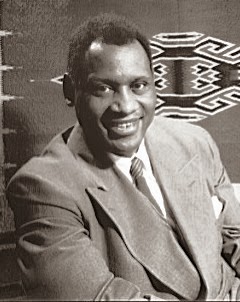

Paul Robeson: Artist and Activist

The Tallest Tree in the Forest, actor and playwright Daniel Beaty’s new

The Tallest Tree in the Forest, actor and playwright Daniel Beaty’s new

one-man show about the life of African American actor, singer, and activist

Paul Robeson, ends with Beaty eulogizing Robeson with some of Robeson’s own

words: “The artist must take sides. He

must elect to fight for freedom or slavery.

I have made my choice.” That

quote, which would become Robeson’s epitaph, provides an accurate summation of

Beaty’s view of Robeson, an artist and performer whose real-life dedication to human

rights causes and early support of the Soviet Union saw him branded as a

Communist by the press and government of the United States and driven out of

show business almost until the end of his life.

Before he came under fire from J.

Edgar Hoover and Senator Joseph McCarthy, Robeson spent a number of years

building a massive following as an international film and theatre star. He is probably best remembered for his role

as Joe in Hammerstein and Kern’s groundbreaking musical Show Boat—specifically,

for his rendition of the show’s most famous song, “Ol’ Man River”—but Robeson

was actually not the first actor to play the role. (He took over from the original Joe, Jules

Bledsoe, when the show opened in London in 1928, and subsequently played the

role twice more on stage, as well as in the 1936 filmed musical.) So great was his popularity that the

lawyer-turned-performer even sang before the Prince of Wales.

Beaty depicts Robeson as a man

constantly at odds with the circumstances of his life: at first in love with

performing, but under pressure from his late father to choose a “respectable”

career in the law; ambivalent about the opportunities for African American

actors, but hen-pecked by his wife and manager, Essie, into taking roles about

which he holds reservations; fiercely attached to his familial and cultural

history in the United States, but somewhat despairing of the possibilities for

positive social change in the country where he was born. Scholars of contemporary African American

theatre and dramatic history, in particular, could find much in this play (in

performance at the Kansas City Repertory Theatre through September 28, 2013) to

focus on.

As an act of scholarly recovery,

one might compare The Tallest Tree in the

Forest to Alice Walker’s “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston.” Just as Walker’s 1975 article for Ms. Magazine helped bring Hurston and

her work back to their rightful place in the body of African American

literature, so does Beaty’s play—which takes its name from the title that

educator and civil rights Mary McLeod Bethune once bestowed on Robeson—seek to

help restore Robeson to his rightful position as an important contributor to

African American theatrical history and to the cause of civil rights.