This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

Outfaulknering Faulkner: Ralph Ellison’s Juneteenth

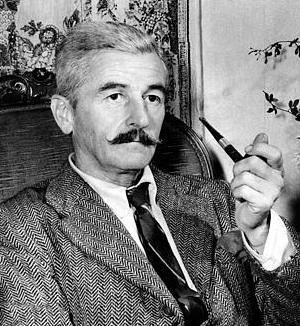

When I reencountered Faulkner as a graduate student, it was in a class that juxtaposed his work with that of 20th Century Black writers. Where I had previously admired him for the way The Sound and The Fury exposed the ugly side of a white Southern aristocratic family, I now came to him with a fuller understanding of the real history of the South, the unromanticized version of the South so rarely acknowledged by whites. I now knew much more about the history of race relations in the South. And so, Faulkner’s questioning of the race binary that pervades Southern thought became especially clear as I began to compare the implicit commentary on the social construction of race in his Light in August with Wright’s Black Boy.

Faulkner’s Joe Christmas and Richard, the self Wright presents in his autobiography, both learn to perform their racial roles through social cues. But where Black Boy’s Richard bucks against that role, eventually leaving the South and achieving self-actualization, once Light in August’s racially ambiguous Joe Christmas is accused of the rape and murder of the white Joanna Burden and thus branded a “nigger,” he is lynched and castrated. Unlike Richard, Joe Christmas does not have the option of transcending his racially prescribed role. He is doomed.

Faulkner’s Joe Christmas and Richard, the self Wright presents in his autobiography, both learn to perform their racial roles through social cues. But where Black Boy’s Richard bucks against that role, eventually leaving the South and achieving self-actualization, once Light in August’s racially ambiguous Joe Christmas is accused of the rape and murder of the white Joanna Burden and thus branded a “nigger,” he is lynched and castrated. Unlike Richard, Joe Christmas does not have the option of transcending his racially prescribed role. He is doomed.

In a letter to Wright after the publication of Black Boy, Faulkner told the author that he had achieved his goal more successfully in Native Son. Wright’s message was important, Faulkner said, and he urged the young Black man to “keep on saying it, but [. . .] as an artist.” In Native Son, of course, Bigger Thomas meets a fate similar to Christmas’s. Unlike Wright himself, Thomas does not transcend the Southern race binary; he is a victim of it. When I first considered the implications of Faulkner’s letter, I came to the uncomfortable conclusion that Light In August offers a harsher critique of the Southern race binary than Black Boy does precisely because Faulkner shows that binary as something that cannot be transcended. That conclusion disturbed me because Faulkner is, after all, still a Southern white man. Enlightened as he may be in comparison to his white peers, he is still undeniably part of the white patriarchy. And so isn’t it at least a little presumptuous of him to claim authority in knowing and presenting the true effects of that patriarchy on black Americans?

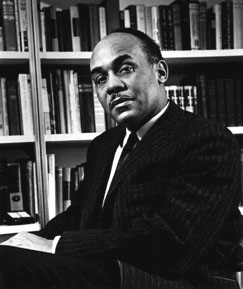

But Faulkner doesn’t have the final literary word on the implications of racial identity, as I learned when I encountered Ellison’s posthumously published novel Juneteenth. In Bliss, the novel’s protagonist, Ellison presents a reading of race that essentially beats Faulkner at his own game. Bliss is racially ambiguous. As is the case with Joe Christmas, the narrative in Juneteenth eventually reveals Bliss’s white mother while the racial identity of his father remains unknowable. There are other hints at Faulknerian influence in the novel, such as the lyrical prose style in the disjointed dream-like passages and the questions of sin and salvation, especially as tied to race, in Bliss’s birth scene. Like Christmas, Bliss had been socialized as Black in his childhood but can “pass” for white as an adult, and it is out of this circumstance that his central conflict in the novel arises. His success as an adult relies on his performance as a white Senator whose platform is vehemently anti-Black. And it is this attempt to alter his racial identity – to perform as not-Black – that eventually leads to his death; Bliss is shot and mortally wounded by a Black man in response to one of his political speeches.

But Faulkner doesn’t have the final literary word on the implications of racial identity, as I learned when I encountered Ellison’s posthumously published novel Juneteenth. In Bliss, the novel’s protagonist, Ellison presents a reading of race that essentially beats Faulkner at his own game. Bliss is racially ambiguous. As is the case with Joe Christmas, the narrative in Juneteenth eventually reveals Bliss’s white mother while the racial identity of his father remains unknowable. There are other hints at Faulknerian influence in the novel, such as the lyrical prose style in the disjointed dream-like passages and the questions of sin and salvation, especially as tied to race, in Bliss’s birth scene. Like Christmas, Bliss had been socialized as Black in his childhood but can “pass” for white as an adult, and it is out of this circumstance that his central conflict in the novel arises. His success as an adult relies on his performance as a white Senator whose platform is vehemently anti-Black. And it is this attempt to alter his racial identity – to perform as not-Black – that eventually leads to his death; Bliss is shot and mortally wounded by a Black man in response to one of his political speeches.

Still, there is a distinct difference in what Bliss’s and Joe Christmas’s deaths illustrate regarding Black identity. Unlike Christmas, Bliss’s death is not immediate. There is time between the injury and his death for him to reflect on the story of his life. By the time of his death, Bliss comes to terms with his Black past, accepting it as part of his identity. The last scene in the novel has Bliss dreaming a group of young black men driving a car that is “an arbitrary assemblage of chassis, wheels, engine, hood, horns, none of which had ever been part of a single car! [. . .] An improvisation, a bastard creation of black bastards – and yet, it was no ordinary hot rod. [. . .] It’s a mammy-made, junkyard construction and yet those clowns have made it work, it runs!” The car represents Black American culture and, in the final moments of the novel, the men driving it bring Bliss aboard. His Black identity is thus something that is essential, something that offers acceptance and hope, a type of salvation. Here there is no need to transcend the binary, just as there is no need to pose Blackness as doomed.

Faulkner likely saw no option other than to doom Joe Christmas because, as a white man, he would have seen Blackness as hopeless. Faulkner did have a strong critique, and it’s important to realize how his ability to see the socially constructed race norms as problematic set him apart from his white peers. In Juneteenth’s Bliss, however, Ellison posits Black identity as possibility.

Faulkner likely saw no option other than to doom Joe Christmas because, as a white man, he would have seen Blackness as hopeless. Faulkner did have a strong critique, and it’s important to realize how his ability to see the socially constructed race norms as problematic set him apart from his white peers. In Juneteenth’s Bliss, however, Ellison posits Black identity as possibility.