Of Nature, Nation, and the Ethnic Body

Editor’s Note: The Project HBW Blog mostly traffics in shorter

Editor’s Note: The Project HBW Blog mostly traffics in shorter

pieces, but from time to time we like to present our readers with a

longer piece, as well, in a feature we call Taking the Long View. For

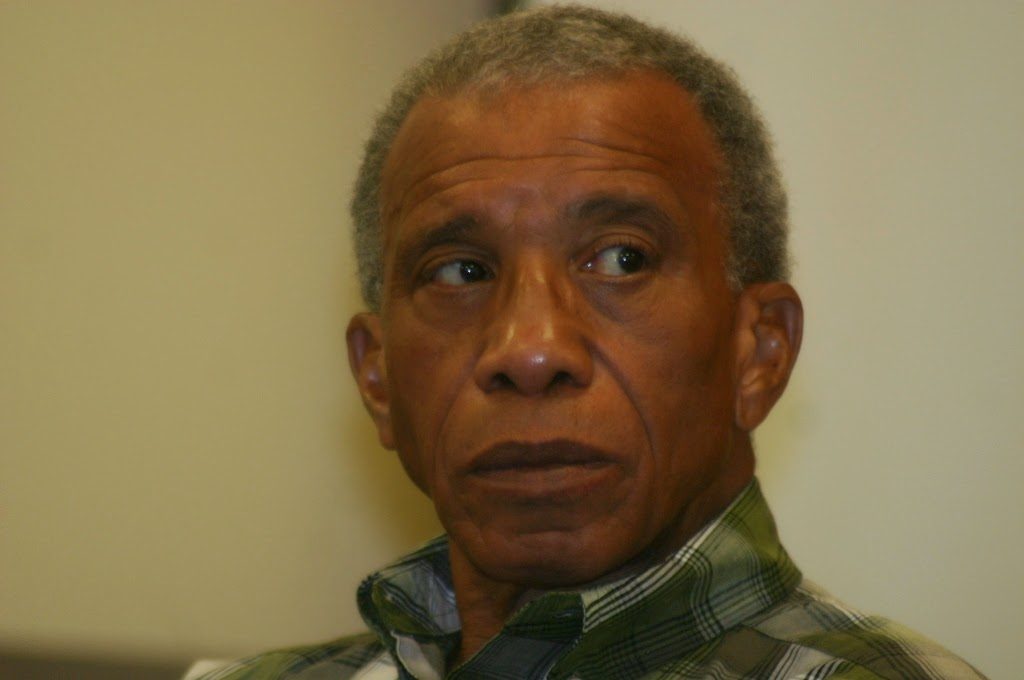

this installment, we feature the poetry and critical reflection of Dr. Jerry W. Ward.

To echo a famous twentieth-century statement, the mind should prompt the mouth to say A BODY IS A BODY IS A BODY, aware that the voiced words refer to and locate an indivisible subject and object. Or perhaps the utterance dislocates the invisible to bring into view, into perspective, a something in the world that the world is determined to impale with the idea that the “something” is ethnic and different and to be talked about. If the something that is so embodied speaks, especially in terms of accepting its ethnicity, the something that is a human being may be contemplating its relationship to nature and to its properties and privileges as a constituent of a nation.

Leave all of that in the conditional. Or export it to POEM, to POETRY. It is poetry and the poem that can facilitate contemplating the mysteries of nature that always outpace human understanding. These mysteries are akin to those which invite consideration of the nature of nations —- the birth, maturation, and death of nations. The will behind the impulse to beget social contracts that are the invisible skeletons of nations. Are all these nations ETHNIC, in one sense or another, by virtue of being combinations of people identified as “ethnic”? Poem, the use of the potential magic of language in its splendid arbitrary nature —ah, the endless shapes that sound assumes. Poem, the vehicle for maximizing our discourses regarding nature and nation and the unstable temporal and spatial identities of bodies assumed and reported to be ethnic. The poem can name the contradictions, the discord of A) having common national or cultural connections and B) having origins, by virtue of birth or heritage, that may or may not correspond with the origins of a specified nation. In this sense, bodies account for their ethnicities. They move in to or out of ethnicity by accident or choice, forever bearing the traces and onus of being or existing. Of all our existing and future genres, it is the poem to which we turn to make sense (and occasionally nonsense) of ethnic motions and notions. The indeterminate status of poem as poem is truly the force that through the green fuse drives the flower.

Here I offer as catalysts for discussion three of my own poems which do not overtly identify my ethnicity because they are, by their nature, beyond both nationality and ethnicity until (and this is the crucial turn) I as the voice of a body interpret them into the imagined spaces marked national and ethnic. The first is “Poem 70,” written to annotate my success in arriving at the age of seventy:

Poem 70

Small, common, not tired

Nor weary nor worn,

Powerful I am

I am an infinite eye/

Voice

Reviving, deriving midnight

From a trinity of signifying parrots—

Passing hep to hopping

The jarring jam they

Dream words

Syntax wax

Grammarians

She and he

Who prismed light—grandeur

Parents razing towers

From/form a sentence —me/I

Apple

Stone immune to polish,

To ignorant charms

Clashing by day,

Superlative subparticles endure—-

Invited to logic wild

Crazy quilting

Wet bones on a mountain,

Fear no evil we/I

Zillion paragraphs

Am defiant dance of chapters,

Have bibled seventy gospels

Shadowed through

The middle between

Of hardships and the rock of ages,

Have published sleep—-

A miracle of invisibility

I am

A purpose to remember.

(Jerry W. Ward, Jr., July 31, 2013)

It is the job of a reader to make intelligent guesses about whether the voice in the poem, the speaking “I,” is a citizen of the United States of America and an African American or a Chinese person who is by heritage a citizen of Cuba. The reader does not know that she is supposed to make such guesses until the poet—who, as author, is no longer related to the poem once it flows freely in the world—proposes that these guesses, rather than a different set of speculations, should be undertaken. Much depends upon where the clues are coming from.

The second poem, “Poem 65,” may have incorporated more clues, especially in my choice to use a line from Walt Whitman as an epigraph. Nevertheless, these clues may depend on the extent of a reader’s cultural literacy.

Poem 65

“Old age superbly rising! Ineffable grace of dying days!”

—Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass

That year love lassoed us

Nailed us to a burning tree.

A trillion stars assumed our minds

Fed us honey and pungent gasoline

In a myth-drenched season.

And want of reason turned us a trope.

In those days a mosquito sang a fatal song

So wrong we cracked bones on a killing floor.

Now in the light of night

Red magnolias blow and children laugh outright

We embrace sanguine memories

Against the fears watered by our fears

Old age and scuppernong have learned us

Charity for the resurrecting past

Tolerance for the blue holes of blessings

Grown ineffable in our eyes and ears.

For some but not all readers who acknowledge their membership within the boundaries of a certain ethnicity, the clues may be the words “killing floor” and “blue holes,” words that in African American speech communities possess special connotations. These words may allude to certain blues lyrics and establish a semantic relationship with blues lyrics. If that is the case, it is appropriate to identify the “we” in the poem with black Americans. Nevertheless, black Americans do not have a monopoly on how words revolve around the concept of ethnicity. The language of the poem has the option of not being ethnic, unless we are willing to identify the concept of ethnicity as a universal item that manifests itself in multiple forms.

The third poem, “Winter Solitude,” speaks of time, a particular season that marks a cycle in Nature, and actions that require no linking to nation or country. It exercises its option to defy ethnicity, to be beyond ethnicity, unless the words “second line,” “segregates,” “peace be still,” and “jazz” are limited to reductive orbits in culture-bound locations. “Second line” does refer to a culture-bound ritual associated with funerals and parade celebrations in New Orleans, Louisiana; the phrase “peace be still” is exported directly from a refrain in an African American gospel song. In this way, the ethnic referents can wear the mask of being associated with Paul Laurence Dunbar’s famous poem “We Wear the Mask.”

Winter Solitude

Funeral follows funeral—

the second line between —

resentment segregates the tombs.

The universe is wrinkled

with the whims and the winds.

Saints cut of silk, frantic like the turf,

wanting terror to touch down,

explode lucid leaves of grass

evermore

for the asking

is nevermore.

The universe is wrinkled

with the whims of mothball hours.

Time. An old man erect,

folding the canals of his bones.

An old woman, pious,

rigid in her rapture on an urn,

grinning toothless passion.

The universe is wrinkled

with the whims of worried days.

Words copulate not

none the less but more.

Salvation burns

where peace be still

is still to be.

The universe is wrinkled

with the whims of stinging seconds

Sounds, jazz iced down,

signal the ending

always beginning

time. Sufferings in ascetic hymns

wash. Absolute soap for the soul.

Primate wings renounce a name.

Yes, seed clichés. Pungent despair

in the fragrant dust. Flowers rust.

Gravity marks wasting time.

(December 21, 2011)

Poems, I would argue, do reveal and conceal what is ethnic in talk about nature and nation, and the ethnic pleasure is in the always-unfinished revolutions of interpretation.