Medgar Evers International Writer’s Conference, Report 2 of 2

Creating Dangerously:

Confronting the Cracks in Oppression that Creators in the African Diasporas Shine Through

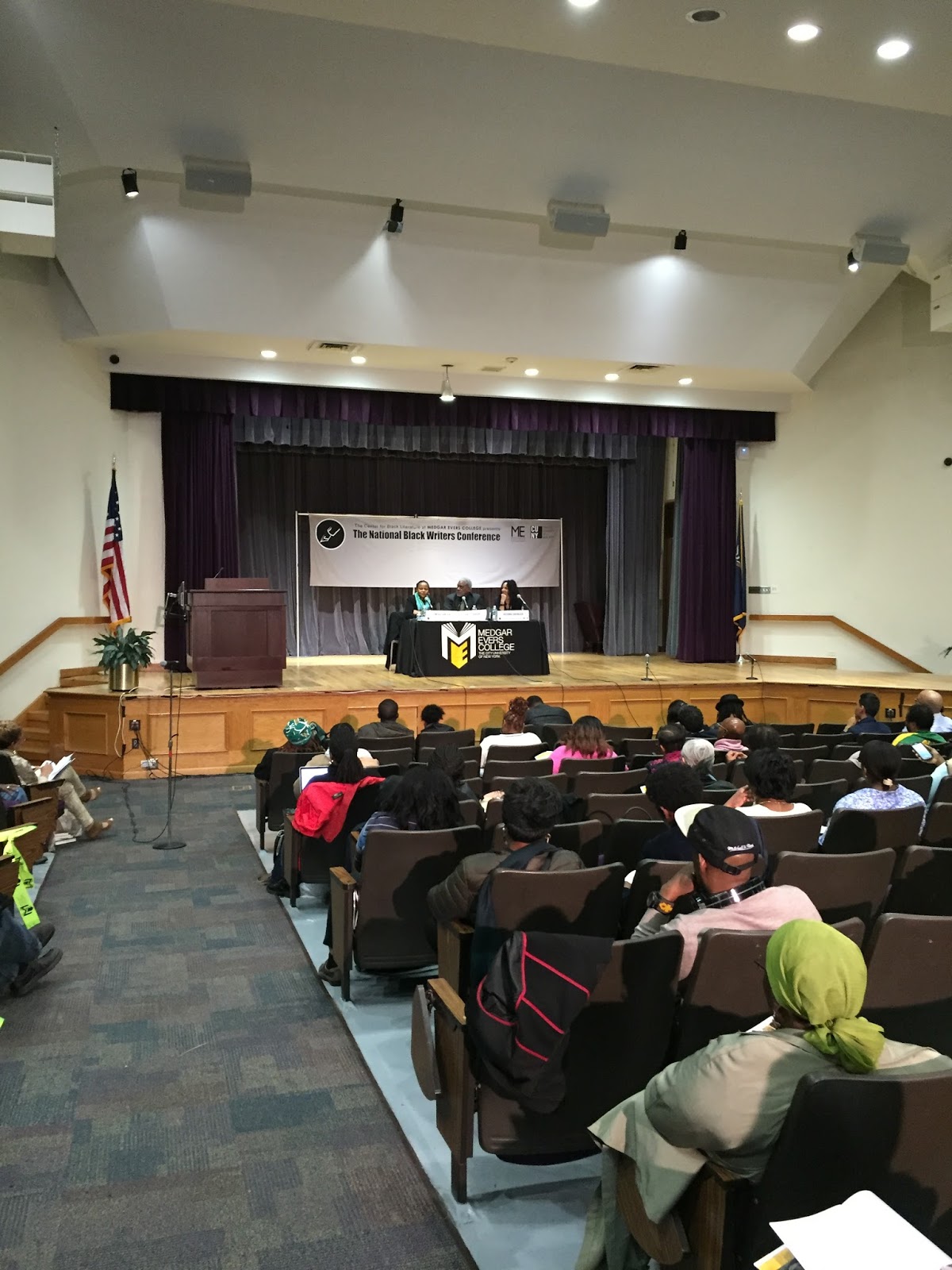

I was not sure what to expect as I entered the auditorium for the fourth time Saturday for the panel, Creating Dangerously: Courage and Resistance in the literature of Black Writers: A Conversation. The conversation was moderated by Victoria Chevalier and featured novelist and short story writer, Edwidge Danticat, and scholar and author, Charles Johnson as panelist. Many of the previous conversations seemed to be coming from a far away place mentally, chronologically, and generationally. Many panelists were reflecting on a time that I was still soaking inspiration from to create a new artistic space in the present, making it difficult to connect my experience as an artist in 2016. I was eager to see how the past was interacting with the present to create an exciting artistic future. Where did I fit in, the 22-year-old poet in the broader conversation of Black art and expression?

Although I do not feel the conference directly addressed my question, this panel did solidify that it’s possible that just by being a black woman, poet, and writer, I am connecting to the past in the inherent politicization of my narrative. Charles Johnson said it best, “Nothing is more radical than addressing the nature of the self: Who am I?” I found that this question rattled the institution of art. When a black woman asks herself who she is and puts it to paper, she is creating a disruption and breaking through an intellectual incarceration that is White Supremacy, as it expresses itself in the literature world. The next question: How do we “murder” and “chip away” White Supremacy in our artistic process and the world. My first thought: despair. How could we possibly answer this question? Danitcat said it plain, “We arm ourselves with all the knowledge and skill and still the problem exists.” My second thought: I am probably among the bravest artistic minds in this moment. When writing my poem about body image or womanhood or unapologetic sensuality, was I unknowingly sharpening the machete of literary warfare? Forcing my narrative in the conversation? If not, what is keeping me from taking Johnson’s suggestions in not policing my imagination? Needlessly to say, it was a lot to consider.

The conversation was not only a war cry for unapologetically searching ourselves and our work, but also a type of theoretical reflection, for in order to create we must first listen. Yes, we must listen to even them. Johnson called it epistemological listening and together Danticat and Johnson addressed the theory of “other.” I began to question my own ideologies around active listening. In the past, the only time that I employed active listening was in my poetry workshops with young students in middle school I was teaching at. It never once occurred to me that I needed to listen to the “other.” Why? What could they say that was going to help me? According to the panelist, many things! Active listening to the other, whoever the other may be, opens us up to further define and inform who we are as artists. Was I active listening to the “other”? Why not? What could I learn by epistemologically listening to other communities and people? It was clear, everyone in the audience had a lot to consider. Mr. Johnson asked a crucial question: “Why write? When writing is at its best, we come out of the story not as clean as when we went in.”

As theoretical as the conversation was, the questions that were posed were very tangible from the panelists’ perspective as well as the Q&A that came after. The conversation began to steer towards White Supremacy in general and its timely death. Could it ever die? Could we kill it? Was it killing itself? The community in the room could agree that White Supremacy, no matter its vitals, needed to go. However, one gentleman asked the question that seemed to stop the room in its tracks and put a crucial crack in a space where we all thought we were on the same page: If we were willing to destroy white supremacy, were we able to destroy all oppressive systems? Down to the lights that were on in the auditorium killing the atmosphere? The panelist looked at each other and lightly chuckled nervously before agreeing and advocating for the erasure of oppression everywhere. I could feel that some of the passion left the room in advocating down to the smallest detail. IT is in these spaces, the light laugh and agreement, that I think it truly gets complicated. As we write our narratives into oppressive spaces, are we making room for other oppressed narratives to speak? Are we using our platform to make room for other oppressed voices, even if it makes us uncomfortable? Most of us want to say yes, but I have a feeling that, as in anything in the creative process, it is never that easy.

During any other panel conversation that left me with more questions than answers, I would be perturbed. However, this panel not only left me with crucial and necessary questions but also the courage to find the answers… by any means necessary.