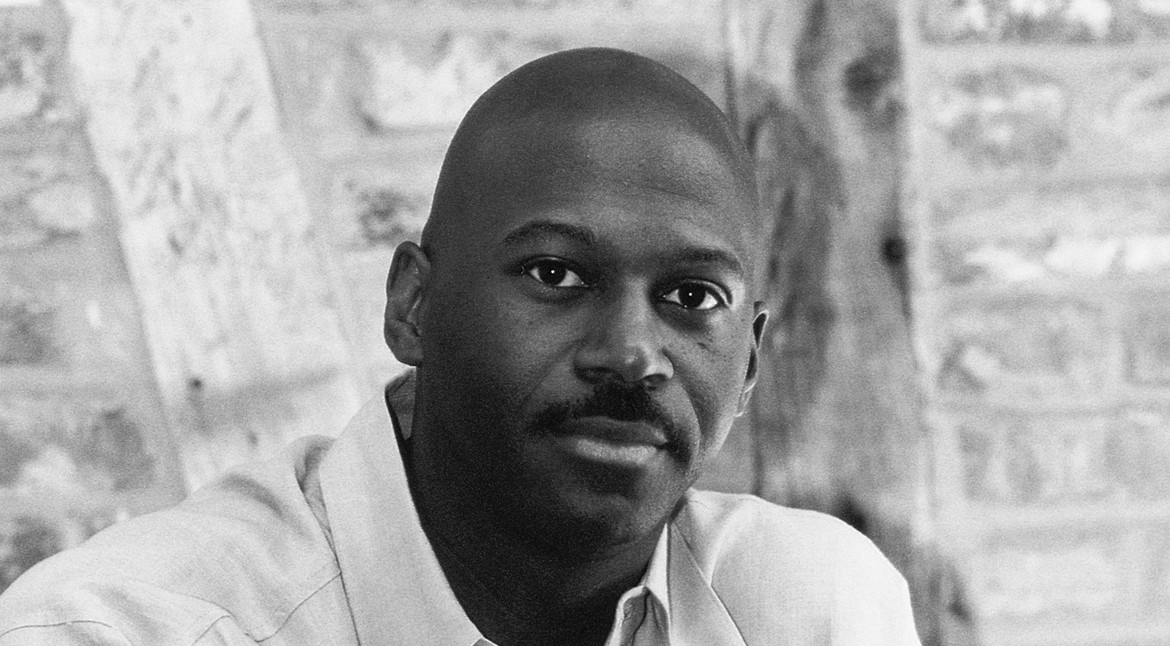

Louis Edwards’s Second Novel

If you like writing that is selective about which second-line parade it will join, you will like the work of Louis Edwards, a native of Lake Charles who probably lives in New Orleans. If you have not seen or talked to a person for several years in the Crescent City, you do best to be cautious about identifying that person’s place of residence. Let it suffice that Louis Edwards lived quietly, at one time or another, in this den of creative temptations without falling into literal or figurative disgrace. That is an achievement.

If you like writing that is selective about which second-line parade it will join, you will like the work of Louis Edwards, a native of Lake Charles who probably lives in New Orleans. If you have not seen or talked to a person for several years in the Crescent City, you do best to be cautious about identifying that person’s place of residence. Let it suffice that Louis Edwards lived quietly, at one time or another, in this den of creative temptations without falling into literal or figurative disgrace. That is an achievement.

Edwards’s first novel Ten Seconds (1991) got better critical praise than many efforts by emerging writers, because he used conceptual imagination and artistry to ensure his story would not be handcuffed by stereotypes. Carl Schoettler’s review in the August 14, 1991 issue of The Baltimore Sun was fair and sensitive to Edwards’s writing an aesthetically challenging novel about a quite ordinary man. Like William Melvin Kelley’s Dunfords Travels Everywheres (1970) and Clarence Major’s Reflex and Bone Structure (1975), Ten Seconds was a fine piece of linguistic invention, indebted to James Joyce but not overwhelmed by the Irish acrobatics. If Bernard W. Bell, who wrote with keen insights about Kelley and who devoted an entire book to Major, had chosen to comment on Edwards’s postmodernism in The Contemporary African American Novel: Its Folk Roots and Modern LiteraryBranches (2004), I suspect Edwards would be more frequently discussed in scholarly circles. Perhaps people who talk about Ronald Sukenick and Richard Brautigan also talk about Edwards. If that is the case, his readership is highly specialized.

Common readers, especially those who live in New Orleans, might embrace his second novel N: A Romantic Mystery (1997). It is rich with street names, place names, food habits, class attitudes —the cataloging we know well from Arthur Pfister’s My Name is New Orleans: 40 Years of Poetry and Other Jazz. You can’t be more New Orleans-centric than Edwards, who in a single paragraph on page 13 mentions Norbert Davidson, Kalamu ya Salaam, James Borders, Brenda Marie Osbey, Tom Dent, Quo Vadis Gex, Keith Woods, Beverly McKenna and the Calliope Project; a writer who has his main character go to Community Book Center to purchase a copy of Jean Toomer’s Cane from Jennifer (page 131) is stone cold New Orleans. Something very special will register for readers who lived in the old New Orleans from 1960 to 2005. The wealth of referentiality might mean little to readers who only know post-Katrina New Orleans, the new city where organic charm has now been commodified for the tourist industry. What will register for all readers, however, is the murder of a young black male. Such murder, unfortunately, is obscenely “normal” in New Orleans. That Edwards chose to use devices from film noir and hard-boiled detective fiction gives what could have been a run-of-the-mill urban novel an intriguing difference. If any real life reporter tried to do what Aimée DuBois does about the crime, she would be cooling in a morgue. The magic in N: A Romantic Mystery is the skill Edwards uses in creating fiction that is historical but not sociological. It is no accident that he dedicated the novel to “Charles Bourgeois and Albert Murray —les gourous” or that most of the chapter titles are French: double entendre, les femmes fatales, la descente, objet d’art, le petit déjeuner, Tante Aimée, le fou, chez Strip, le cinema, la nature morte, Doppelgänger (a German slip), l’entracte, le livre, la vie en rose, sang-froid, chef d’oeuvre, la niece, les morts ne parlent pas, le pasteur, un coup de telephone, la resurrection de l’amour, vive la difference, la letter d’or, and dénouement (this final chapter rounds off the sections LES PROLOGUES, ACTE I: Mise en Scène, L’ENTRACTE, ACTE II: À la Recherche du Temps Perdu). Edwards’s second novel is sufficiently Louisiana African/American French to distinguish itself from the genre of street literature. It is not ti negre; it is simply Black.

Common readers, especially those who live in New Orleans, might embrace his second novel N: A Romantic Mystery (1997). It is rich with street names, place names, food habits, class attitudes —the cataloging we know well from Arthur Pfister’s My Name is New Orleans: 40 Years of Poetry and Other Jazz. You can’t be more New Orleans-centric than Edwards, who in a single paragraph on page 13 mentions Norbert Davidson, Kalamu ya Salaam, James Borders, Brenda Marie Osbey, Tom Dent, Quo Vadis Gex, Keith Woods, Beverly McKenna and the Calliope Project; a writer who has his main character go to Community Book Center to purchase a copy of Jean Toomer’s Cane from Jennifer (page 131) is stone cold New Orleans. Something very special will register for readers who lived in the old New Orleans from 1960 to 2005. The wealth of referentiality might mean little to readers who only know post-Katrina New Orleans, the new city where organic charm has now been commodified for the tourist industry. What will register for all readers, however, is the murder of a young black male. Such murder, unfortunately, is obscenely “normal” in New Orleans. That Edwards chose to use devices from film noir and hard-boiled detective fiction gives what could have been a run-of-the-mill urban novel an intriguing difference. If any real life reporter tried to do what Aimée DuBois does about the crime, she would be cooling in a morgue. The magic in N: A Romantic Mystery is the skill Edwards uses in creating fiction that is historical but not sociological. It is no accident that he dedicated the novel to “Charles Bourgeois and Albert Murray —les gourous” or that most of the chapter titles are French: double entendre, les femmes fatales, la descente, objet d’art, le petit déjeuner, Tante Aimée, le fou, chez Strip, le cinema, la nature morte, Doppelgänger (a German slip), l’entracte, le livre, la vie en rose, sang-froid, chef d’oeuvre, la niece, les morts ne parlent pas, le pasteur, un coup de telephone, la resurrection de l’amour, vive la difference, la letter d’or, and dénouement (this final chapter rounds off the sections LES PROLOGUES, ACTE I: Mise en Scène, L’ENTRACTE, ACTE II: À la Recherche du Temps Perdu). Edwards’s second novel is sufficiently Louisiana African/American French to distinguish itself from the genre of street literature. It is not ti negre; it is simply Black.