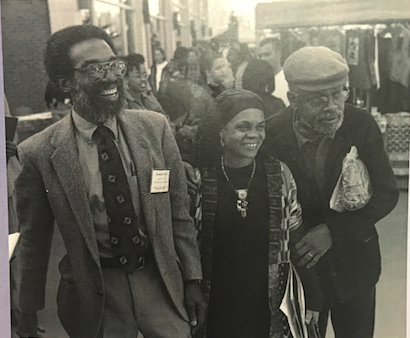

Lorenzo Thomas (1944-2005)

Categories: HBW

Lorenzo Thomas (1944-2005)

As I reread a few of Lorenzo Thomas’s essays and poems, I recall the first line of Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” —

“I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving

hysterical naked….”

The single word in the beginning of Ginsberg’s semi-autobiographical, derivative tribute to Walt Whitman that captures attention is “minds,” although the current visibility of mental illness and homelessness in the USA might derail that focus. Madness, which isn’t identical with insanity, and the companion images of hysteria and lack of food and clothing invite aesthetic adventures which are tangential ( and perhaps beside the point). Over the past thirty years, criticism and theory have encouraged more concern with the material body than with the abstract operations of the mind. Enthralled by such emphasis, many a fine poet has plunged into innovation, outing, and shock-value. The dullness of post-WWII America may have justified Ginsberg’s wanting to approach the surrealism of Bob Kaufman to protest how poetic expression was imprisoned. The jury is still out on that possibility. Reading Thomas against the sweep and gestures of “Howl,” I am intrigued that as one of the best minds of my generation Thomas chose to dismiss the limits of protest and to map new territories for African American creative work. Thomas invested heavily in language, history, and the mind.

One small instance of Thomas’s superior mind occurs in an interview Charles Rowell conducted with him in 1978 (“Between the Comedy of Matters and the Ritual Workings of Man” ). When Rowell suggested that Thomas might “probably agree with W. H. Auden’s “In Memory of W. B. Yeats” — that “poetry makes nothing happen,” Thomas finessed the moment by saying that Auden’s assertion was right, but that Black poets are interested in Yeats as “a nationalist and an activist and a mythologist as well.” It was not Yeats’s making of poems and theater pieces that made anything happen, “but their presence in people’s consciousness is what made things happen. In a few simple words, Thomas accurately contextualized and deconstructed a reprehensible stereotype by using plain ancient Egyptian common sense rather than complex, deceptive European-derived jargon. Whether they are experimental or traditional, poets are not ethnic commodities in pre-future cargo ships. Thomas stood on the shoulders of Langston Hughes. He understood clearly the aesthetic kinship of poets and musicians and what ought to count as valid in matrices of creative expression. There is lasting relevance in the point Thomas made regarding what was problematic in the Black Arts Movement and is still problematic in the reception of American poetry: “The concept of the poem functioning as a political entity —as rhetoric that was to be acted upon –was and is a mistaken notion. The poem creating consciousness, which will then inspire people to act, is valid.” I attribute Thomas’s excellent insight to his possessing a unique blending of African Diaspora, Central American, and New York sensibilities.

Challenge my high regard for how Thomas mapped territory by going to the sources, by reading his eloquent essays in Extraordinary Measures: Afrocentric Modernism and Twentieth-Century American Poetry (2000) and Don’t Deny My Name: Words and Music and the Black Intellectual Tradition (2008). Challenge your own literacy by reading his major collections of poetry —The Bathers (1981), Chances are Few (1979; and the expanded second edition, 2003), and Dancing on Main Street (2004). Try to avoid being complicit in allowing your mind to be “destroyed by madness” in 2017.

March 23, 2017