This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

Lance Jeffers (1919-1985): WRITING TOWARD BALANCE

Equating the power of Lance Jeffers’ mind with intellectual passion, Eugene Redmond proclaimed in his introduction for When I Know the Power of My Black Hand (1974) that Jeffers was “a giant baobab tree we younger saplings lean on, because we understand that he bears witness to the power and majesty of ‘Pres, and Bird, and Hodges, and all’ “(11). In bearing witness to fabulous musicians, Jeffers left evidence in his poetry and his novel Witherspoon (1983) that the art of writing well entails finding a balance between the kind of humility to which Redmond alludes and the mastery of craft.

Equating the power of Lance Jeffers’ mind with intellectual passion, Eugene Redmond proclaimed in his introduction for When I Know the Power of My Black Hand (1974) that Jeffers was “a giant baobab tree we younger saplings lean on, because we understand that he bears witness to the power and majesty of ‘Pres, and Bird, and Hodges, and all’ “(11). In bearing witness to fabulous musicians, Jeffers left evidence in his poetry and his novel Witherspoon (1983) that the art of writing well entails finding a balance between the kind of humility to which Redmond alludes and the mastery of craft.

In an interview with Paul Austerlitz included in Jazz Consciousness: Music, Race, and Humanity (Middletown, Ct: Wesleyan University Press, 2005), Milford Graves speaks about his interest in

Einstein and quantum physics. John Coltrane was also immersed in study of Einstein’s physics. In the poetry of Asili Ya Nadhiri, one discovers his indebtedness to jazz and physics, just as one finds in Jeffers’ poetry an indebtedness to the study of anatomy, jazz and classical music. Strong poets and strong musicians are receptive to mastering their craft by making intellectual investments in disciplines which, on the surface, seem remote from their own. Assertive humility is important.

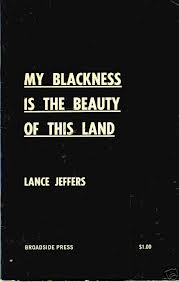

Humility may be alien in contemporary American life, but it is necessary for our respecting tradition and ourselves as saplings in need of guidance from baobabs, redwoods, and oaks. Reading all of Jeffers’ poems in My Blackness is the Beauty of This Land (1970), When I Know the Power of My Black Hand, O Africa Where I Baked My Bread (1977) and Grandsire (1979) is a rewarding use of time. We learn to locate ourselves in human history. We learn that direct confrontation and battle with language is more valuable than intimacy with clichés.

Jeffers used rhyme with discretion, but he maximized repetition of parts to intensify the “epic line” American poets have inherited from Walt Whitman. The epic line projected Jeffers’ passionate attention to small things and big events in historical experiences. Surreal phrasing is a typical feature in his work, a feature that also flavors the poetry of Bob Kaufman. Consider Jeffers’ “in the sea the anchor of your/ soul rushes to the surface on flying fish’s wings” or “The hawk is slavery still alive in me/ my testicles afloat in cotton field.” How many blues songs swam through his mind when he wrote “My own flesh has been nailed so strait/ I’ve been forgot by my own genius”? Exploration of Jeffers’ poetic landscape yields moments of technical brilliance, moments that challenge us to find our own wordpaths to similar achievements. We must know what the ancient rain can bring.

When I ended “Second April Poem (for Lance Jeffers)” with the lines

People

who want to be

the

alpha and omega

ought

to take lessons

from

my friend Lance

who

made morality a verb.

I thought of how Old Testament his prophecy was. He was unashamed in testifying about the evil and the good in human beings. He had conviction and character. He was willing to predict that a male poet “will explore the unexplored continent of himself and his people, will seek out the hidden caves and springs of beauty and hell, will seek out the hell and the complexity within his bones and within the viscera of his people” (“The Death of the Defensive Posture,” 259). These thundering words come from his seminal essay in The Black Seventies (Boston: Porter Sargent, 1970), edited by Floyd B. Barbour. His referring us to land masses and body parts is indicative of his “scientific” posture with regard to discovering truths about humanity. References to geography and anatomy recur in his poems; they reinforce the sense of greatness or grandeur. His aesthetic is grounded in humanistic, pre-Black Arts assumptions about the human condition, but his poetics is grounded in relentless investigation of what the human condition is from the vantage of Blackness. His “humanistic” response to writing as a way of knowing was an effort to balance logic with sensual saturation. His writing is a fine example of how universally inseparable are art and ethos.

From reading Lance Jeffers, not once but many times, we may learn the value of disciplined uses of language, of exorcising demons that seek to persuade us that we have no obligations as poets to our biological and literary ancestors and descendents. Truth be told, we can learn to write well from many poets other than Lance Jeffers. Whether they can teach us as well as his works can the validating beauty of writing toward balance is a matter for contemplation.