This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

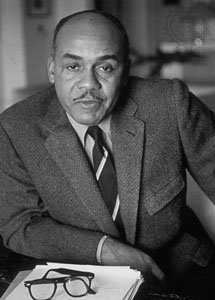

A Lament for Ralph Ellison

HBW Board Member Prof. Jerry Ward responds to questions posed on the HBW Blog and Facebook Accounts

HBW Board Member Prof. Jerry Ward responds to questions posed on the HBW Blog and Facebook Accounts

QUESTION: The Invisible Man creates a space outside of time where he indeed can begin to imagine and construct new relations between the past and present as well as art and technology. By doing so, he creates a new black future. How can I expand upon this thought with other literary examples?

With so many political issues being discussed in black novels, how do you distinguish from political propaganda and art? Or, is it both? In other words, would some black writers write just for art’s sake and happen to have political sentiments in the work?

Throughout the novel, the protagonist concludes that his invisibility stems from the fact that he is unable to define himself outside the influence of others. There is a lack of agency that is attributed to blackness. Nearly everyone that he encounters throughout the novel attempts to tell him who and what he should be. Thus, his going underground literally is an attempt to define himself for himself outside of time and space (everyday ebb and flow) while still confined by that same time and space. Is this a correct reading of Ellison’s Invisible Man? What other literary works deal with these ideas of visibility and invisibility? It doesn’t have to be a literal invisibility, but perhaps being ignored or overlooked.

ANSWER: Your questions are catalysts for meaningful literary conversation as well as cultural criticism. We have a surplus of criticism. Conversation based on cultural literacy and awareness of historical location is rare in the United States.

Consider that the nameless narrator in Invisible Man (1952) only has voice and presence because we are reading Ellison’s text. It is in a reader’s mind that marks on a page or specks on a screen (reproduced from Ellison’s manuscripts/typescripts) are transformed into literature.

Reading in “a space outside of time,” a reader mirrors the narrator in her or his own image. There is no single “correct reading” of Invisible Man. It is only by way of consensual argument that readers approximate good but not absolutely correct interpretations. When a correct reading of a text manifests itself in this world, we no longer have a reason to read that text. Correcting what is correct is a romantic waste of time. By virtue of specific referentiality, on the other hand, we can sometimes arrive at “correct readings” on nonfiction texts.

It is a reader’s mind that constructs “new relations between the past and present as well as art and technology.” A black reader no more creates a new black future than a Russian reader creates a new Russian future. Reading makes possible conditions for a future. This principle liberates you to expand your thoughts regarding space and time by selecting example from world literature. The principle does not enable you to create a future, except in the sense a metaphor creates a future. The construction and deconstruction of Zeitgeist is a bio-cultural phenomenon not an act of reading.

Reading does create agency. It allows you to link art and technology. Think of art and technology in relation to Ralph Ellison’s novels. For example, the first sentence in Chapter 1 of Ellison’s unfinished second novel Juneteenth (New York: Random House, 1999) is “Two days before the shooting a chartered planeload of Southern Negroes swooped down upon the District of Columbia and attempted to see the Senator.” The first sentence is the Prologue of Ellison’ unfinished second novel Three Days Before the Shooting… ( New York: The Modern Library, 2010) is “Three days before the shooting a chartered planeload of

Southern Negroes swooped down upon the District of Columbia and attempted to see the Senator.” Your agency matters. So too does the difference between two days and three days. So, what up?

What is up departed with Ralph Ellison’s soul on April 16, 1994. What we have to be down with is the fact that blue, red, black, green, yellow, brown, white and pink novels all deal with art and political issues. As W. E. B. DuBois asserted in “Criteria for Negro Art (1926), “all art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists.” All propaganda, however, is not art, because propaganda is split-tongue trash talk in the service of somebody’s ideologies. The whole history of the all novels written to date involves the weaving of art and propaganda. It is a hellish exercise to separate art from propaganda. Frankly, art and propaganda are like jazz: if you must ask what they are, you damned sure do not need to know.

Without constructive malice (see Black’s Law Dictionary for a definition), John F. Callahan tried to finish the unfinished work of Ellison’s soul by arranging a reader’s edition of the second novel from the “notes,

typescripts, and computer printouts and disks” Ellison created over a forty-year period. Callahan promised in “Afterword: A Note to Scholars” to create a scholar’s edition to document his corrections of Ellison’s work “and include sufficient manuscripts and drafts of the second novel to enable scholars and readers alike to follow Ellison’s some forty years of work on his novel-in-progress” (Juneteenth 368) With the help of Adam Bradley, Callahan kept his promise. We now have Three Days Before the Shooting…, all 1101 pages.

This scholar’s edition is a treasury of “ideas of visibility and invisibility,” an icy mirror of the invisibility and visibility of Ralph Ellison’s life, a life worthy of Greek tragedy. Read Lawrence P. Jackson’s Ralph Ellison: Emergence of Genius (2002) and Arnold Rampersad’s Ralph Ellison: A Biography (2007) to get my drift and to grasp the reason that lamenting Ellison’s life is an act of compassion. The white witch of fame plucked Ellison clean as far as his writing a second novel went.

There is no lack of agency in blackness. If we have an opportunity to see

INVISIBLE MAN

adapted by Oren Jacoby

based on the novel by Ralph Ellison

directed by Christopher McElroen

This savage, hypnotic, and impassioned adaptation of Ralph Ellison’s 1952 masterpiece explores bigotry and its effects on the minds of both victims and perpetrators.

we shall know just how much agency blackness has.