This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

Kiese Laymon on the Power of Revision and Description

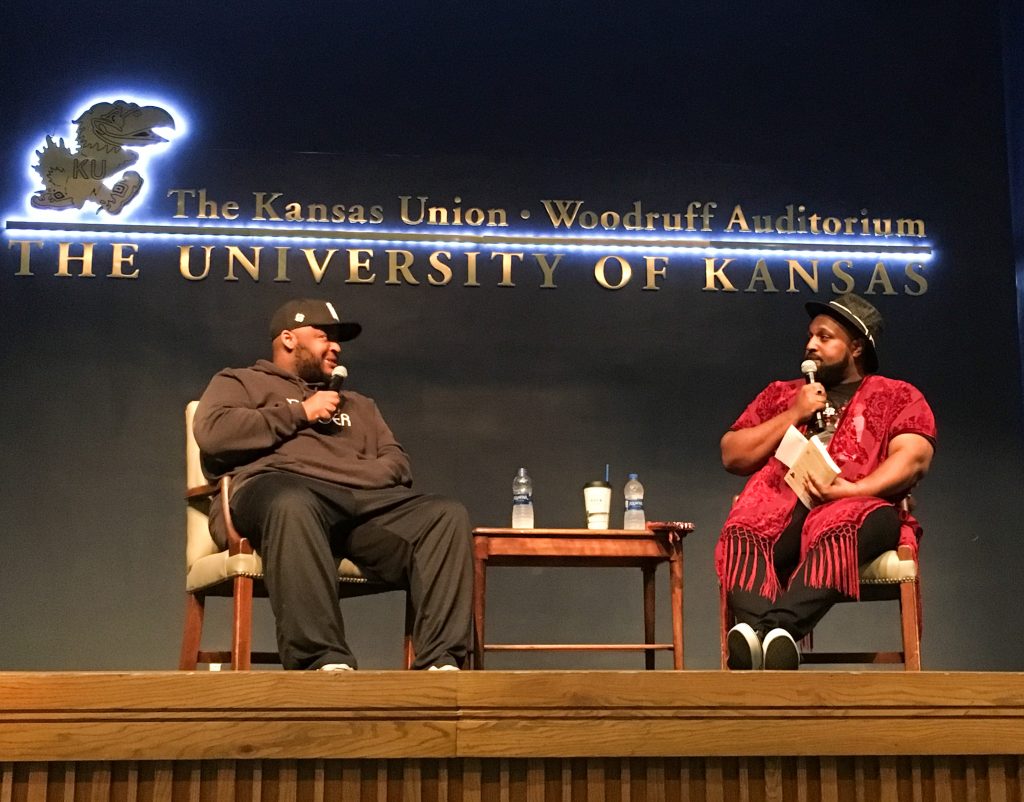

On October 3rd KU welcomed critically-acclaimed author Kiese Laymon to the Lied Center to deliver the 2019 Common Book Lecture. Laymon is a contributor in this year’s common book, Tales of Two Americas: Stories of Inequality in a Divided Nation, and has authored a number of books including his debut novel Long Division, an award-winning collection of essays titled How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America, and most recently Heavy: An American Memoir, winner of the Carnegie Medal for Nonfiction and a New York Times Best Book of 2018.

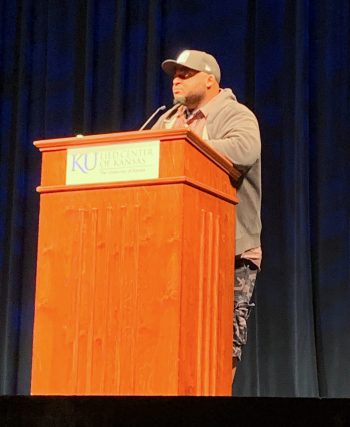

During his lecture Laymon read a revised version of his original featured essay titled “Outside.” His discussion described the importance of revision, not only in the literary world, but also in our everyday lives. As he stated, “just because something is published doesn’t mean it’s finished.”

Reading an excerpt from “Outside,” Laymon articulated how we can learn to revise our lives and how we can learn from our mistakes. Recounting his experience during his first year of teaching at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, Laymon described all the struggles and failures he faced, from trying to be his students’ counselor-parent-teacher, to dealing with the problems of institutionalized racism and the broken justice system. One story Laymon shared was from his time serving on the school’s judicial board during a hearing for a white student who had been caught with cocaine in his room. The student had a full sales setup, which included bags, scales and “product.” However, in his appeal the student stated that a “big, dark man forced him to buy the cocaine.” The student’s plea for sympathy lead the board to dismiss the case and he faced no repercussions.

Doubting the validity of the student’s encounter, Laymon opposed the ruling and posed the question as to why someone would coerce a person to buy their cocaine, when instead they could take the money and keep their cocaine. Laymon’s question was intended to dispel the student’s blatantly racist suggestion that he was “forced” to buy the cocaine by a “big, dark, man,” whereas the board’s decision was made on the basis that they didn’t know what the student’s experience was.

Laymon tied this back to his own experience as he was kicked out of college 10 years prior for taking a library book. Laymon explained that he had friends currently doing time in jail for far less cocaine than this, “small, smart, white boy.” His story helped put into perspective not only the racial injustices that persons of color face within the incarceration system, but also the injustices faced in the world of academia. Laymon explained that his experience at Vassar College felt like he was confined to a dichotomy between old and new “Blackwork,” explaining, “teaching wealthy white boys like him meant to me that I was really being paid to fortify their power… that felt like new work to me, but it also felt like old Blackwork.”

Laymon tied this back to his own experience as he was kicked out of college 10 years prior for taking a library book. Laymon explained that he had friends currently doing time in jail for far less cocaine than this, “small, smart, white boy.” His story helped put into perspective not only the racial injustices that persons of color face within the incarceration system, but also the injustices faced in the world of academia. Laymon explained that his experience at Vassar College felt like he was confined to a dichotomy between old and new “Blackwork,” explaining, “teaching wealthy white boys like him meant to me that I was really being paid to fortify their power… that felt like new work to me, but it also felt like old Blackwork.”

Often in academia people of color are made to feel like they are “lucky” to be here, or that they should feel “privileged” that they didn’t end up like other members of their community, when in reality more people from multiply-marginalized backgrounds aren’t in higher education because of the institutionalized obstacles placed in their way. Educating dominant society on their power and privilege isn’t new work, but rather work that people of color have been doing for decades.

Following the theme of educating others in an answer to a question that mentioned the “sad and depressed” system, Laymon explained that “learning how to accurately describe the system which you called sad and depressed is in it of itself a kind of liberatory act.” In order to create change and find ways to fix the broken system, we need to be able to educate others and learn to “accurately describe power and then think about our complicity in that system.” Change comes from within, and to create that change, we need to learn to accurately describe our experiences and explain the power and privilege within those experiences.

While most of the conversation was directed towards incarceration and the inequalities within that system, Laymon continued to return to the same inequalities which are present in institutions of higher education. “What I believe in even less than incarceration is the inequity that I see and feel in institutions all over this country,” Laymon said, pointing out the realities that many people from historically oppressed backgrounds face when in academia. In a world full of obstacles and inequity, marginalized persons continually have to fight for the right for their voices to not only be heard, but understood.

While most of the conversation was directed towards incarceration and the inequalities within that system, Laymon continued to return to the same inequalities which are present in institutions of higher education. “What I believe in even less than incarceration is the inequity that I see and feel in institutions all over this country,” Laymon said, pointing out the realities that many people from historically oppressed backgrounds face when in academia. In a world full of obstacles and inequity, marginalized persons continually have to fight for the right for their voices to not only be heard, but understood.

As Laymon stated, “we all have work to do, but sometimes that phrase obscures the terror implicit in not doing the work; how do we celebrate and love out of relationships without simply doing the bare minimum?” This was something that really resonated with me because often I do the bare minimum, and that is worrying because in a world so full of hate how do I do the work to love others and validate their experiences? This also exposed me to new ideas and thoughts which I learned, and in turn forced me to work through and understand how my own identity fits into it, and what is the work that needed to be done.

Many imperative and valuable conversations were had throughout the span of both days, but overall my major takeaways from both conversations were the importance of revision, description, and discovery. The significance of revising and rebuilding ourselves and our work, accurately describing our experience, power, and privilege, and discovering who we are and building on that to further explore who we want to be. To encompass it all in the words of Laymon, “we need to remind ourselves that there are other people coming after us and they need to be able to see what y’all have experienced, felt, seen, and thought…It’s a way of archiving history to actually write about what you think and feel and see in the moment.”

Victoria Garcia Unzueta is a freshman here at the University of Kansas. Victoria is majoring in journalism with an emphasis in strategic communications. She is apart of the Center for Undergraduate Research’s Emerging Scholars program, which placed her with HBW. Victoria is originally from Dodge City, Kansas where she was editor in chief of her highschool’s newspaper and yearbook. For Victoria, these experiences helped shape her passion for journalism and community advancement and helped her to find HBW, where she hopes to continue the important work being done.

Victoria Garcia Unzueta is a freshman here at the University of Kansas. Victoria is majoring in journalism with an emphasis in strategic communications. She is apart of the Center for Undergraduate Research’s Emerging Scholars program, which placed her with HBW. Victoria is originally from Dodge City, Kansas where she was editor in chief of her highschool’s newspaper and yearbook. For Victoria, these experiences helped shape her passion for journalism and community advancement and helped her to find HBW, where she hopes to continue the important work being done.