This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

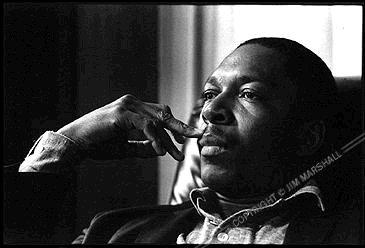

Jazz and Rhetoric: Notes on John Coltrane

There are few jazz artists that have been written about as much as John Coltrane. On one hand, there are his many musical accomplishments that changed jazz forever. Born September 23, 1926 in Hamlet, North Carolina, Coltrane went from a side-man in Philadelphia based blues bands to performing with legends of jazz such as Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk and Dizzy Gillespie, to leading an illustrious solo career with his own quartet. Along with an infamous victory over drug and alcohol abuse, Coltrane was able to remain on the cutting edge of jazz’s evolution right up until his death in 1967 from liver disease. Coltrane is most well-known for his album A Love Supreme and the album itself is heralded as a jazz classic. Although Coltrane and this album in particular have been approached from many other academic disciplines, there is however only a small amount in terms of rhetorical analysis and criticism. The album is structured as a suite split into four parts; “Acknowledgement,” “Resolution,” “Pursuance,” and “Psalm.” The album is a mixture of hard bop and free jazz with “Psalm” and the beginning of “Acknowledgement” being free jazz.

I believe there is a gap in scholarship on Coltrane, one devoid of specific rhetorical analysis. I want to expound on the current scholarship regarding rhetoric and music and address what I perceive to be as a gap in the understanding of the rhetorical function within the aural and compositional component of music by forming a bridge between the theoretical frameworks built from rhetoric scholarship and those deriving from a specific African American epistemology. Some scholars stop short of crediting music without lyrics as “functioning as rhetorical artifact.” I take issue with this particular notion because it perpetuates a vagueness over theorizing about music, and it limits the ways we might begin to understand it. Instead I would contend that when considering music without lyrics we view compositional decisions in a dialectical context, especially when the music can easily be seen as didactic.

I believe there is a gap in scholarship on Coltrane, one devoid of specific rhetorical analysis. I want to expound on the current scholarship regarding rhetoric and music and address what I perceive to be as a gap in the understanding of the rhetorical function within the aural and compositional component of music by forming a bridge between the theoretical frameworks built from rhetoric scholarship and those deriving from a specific African American epistemology. Some scholars stop short of crediting music without lyrics as “functioning as rhetorical artifact.” I take issue with this particular notion because it perpetuates a vagueness over theorizing about music, and it limits the ways we might begin to understand it. Instead I would contend that when considering music without lyrics we view compositional decisions in a dialectical context, especially when the music can easily be seen as didactic.

There are an immense amount of nuances and subtleties that must be considered in order to analyze this album from a cultural perspective. That is why I believe that this type of rhetorical analysis should also draw upon theoretical frameworks that are derived from both standard rhetoric scholarship and from an African American epistemology. The analysis of music then could be conceived as an analysis of comparative styles through the examination of juxtaposed forms and by placing the rhetorical function of music in a dialectical context.

This idea works well for conceiving of Coltrane’s decision to compose A Love Supreme in such a way that combined the styles of hard bob and free jazz as not only groundbreaking in terms of the music but also rhetorical in nature. Listeners are forced into approaching the music with the same sensitivity and complexity that is normally reserved for classical music. It also presents a particular fusion of the traditional styles of jazz, the African American gospel tradition, and an avant-garde conception of the jazz artist as an intensely intellectual and spiritual artist. Analyzing Coltrane’s compositional decisions from a rhetorical perspective allows us to cross this line on a certain level and include him as a receiver, interpreter, and contributor to this rhetorical landscape. Without a concrete approach that can link Coltrane to these concepts we are left with making more abstract claims that work more on a metaphysical level.

This idea works well for conceiving of Coltrane’s decision to compose A Love Supreme in such a way that combined the styles of hard bob and free jazz as not only groundbreaking in terms of the music but also rhetorical in nature. Listeners are forced into approaching the music with the same sensitivity and complexity that is normally reserved for classical music. It also presents a particular fusion of the traditional styles of jazz, the African American gospel tradition, and an avant-garde conception of the jazz artist as an intensely intellectual and spiritual artist. Analyzing Coltrane’s compositional decisions from a rhetorical perspective allows us to cross this line on a certain level and include him as a receiver, interpreter, and contributor to this rhetorical landscape. Without a concrete approach that can link Coltrane to these concepts we are left with making more abstract claims that work more on a metaphysical level.

Coltrane’s resonance with the Black Nationalist Movement, African American community, and the American public in general reflects his ability to not only transfigure their ideals concerning the potentialities of human expressive power but more specifically articulate a spiritually enlightened modern black consciousness that was fully aware and responsive to the complexity of issues facing the hearts, minds and souls of his listeners.