This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

“If I have seen far, it is because I am perched upon the shoulders of giants” – A Reflection

We are, quite likely, familiar with the statement, “If I have seen far, it is because I am perched upon the shoulders of giants.” Dr. Ward (HBW Board Member Emeritus) pinpoints seven of several pillars whose writing could be thought to undergird the work the Project on the History of Black Writing has accomplished throughout its 35-year existence. He notes also the “culture of professional civility” maintained and advanced within HBW in an effort to create truly collegial space for students and scholars all along the academic continuum, a hallmark of the project, and goes on to enumerate many of the projects HBW has undertaken, from bibliographic work to current efforts to digitize its holdings, making them key-word searchable. Dr. Ward’s assertions present a kind of paradox: they at once anchor HBW in the rich African American literary tradition while also acknowledging its unique culture, its deft alignments and realignments, and an undaunted spirit of evolving purpose that constitute a fabric of purposeful dynamism.

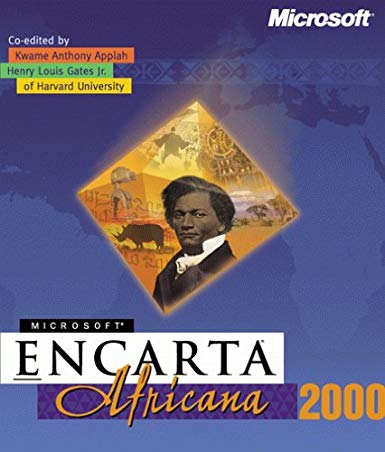

Our early work in the Project at KU resonates with these elements. Soon after its arrival to KU, the Project was tasked with contributing to the massive Encarta Africana digital encyclopedia. At the 2018 College Language Association Convention, Dr. Graham highlighted the pivotal role partnerships have played in the evolution of HBW. Encarta Africana was among the first of those multi-layered partnerships. Every bit and byte of material we provided to the partnership was either mined from the already substantial HBW archive or was thoroughly sleuthed, searched, and sought-for. My experience was precedent-setting. Even after I left Lawrence, that spirit of collegiality and the drive to enculture a community of learners took root in my new high school environs and HBW fanned the embers through its support of a Langston Hughes Literary Circle at the high school. Never before, nor since have elements across the spectrum of our school community come together outside of class, at the end of the school day to read and to discuss Black writing. Our circle, comprised of faculty members from across departments, students, alumni, parents, and staff members stands alone in its representation of multiple stakeholders in our community.

Our early work in the Project at KU resonates with these elements. Soon after its arrival to KU, the Project was tasked with contributing to the massive Encarta Africana digital encyclopedia. At the 2018 College Language Association Convention, Dr. Graham highlighted the pivotal role partnerships have played in the evolution of HBW. Encarta Africana was among the first of those multi-layered partnerships. Every bit and byte of material we provided to the partnership was either mined from the already substantial HBW archive or was thoroughly sleuthed, searched, and sought-for. My experience was precedent-setting. Even after I left Lawrence, that spirit of collegiality and the drive to enculture a community of learners took root in my new high school environs and HBW fanned the embers through its support of a Langston Hughes Literary Circle at the high school. Never before, nor since have elements across the spectrum of our school community come together outside of class, at the end of the school day to read and to discuss Black writing. Our circle, comprised of faculty members from across departments, students, alumni, parents, and staff members stands alone in its representation of multiple stakeholders in our community.

The most recent effort to revive the Lit Circle is a collection of faculty members across the curriculum who meet weekly for discussions related to their reading of Ellison’s Invisible Man. African-American writing and the modes of inquiry that attend to it are so inextricably woven into the HBW fabric that it takes little to replicate its culture of collegiality and inquiry.

Saint Ignatius College Prep will celebrate its sesquicentennial in two years. I would argue that the three events that shifted this Jesuit high school’s culture paradigm most drastically have been (in order) (1) The move to become a co-educational institution in 1979, (2) The startling paucity of Jesuit educators (and the attendant ballooning of lay educators), and (3) Pedagogical advances that broaden the scope of a student’s experience by leveraging her earnest desire to absorb knowledge and to learn with an increased expectation of her responsibility to achieve mastery – which is ironic given the Jesuits’ reputation as challengers of the status quo and their quest to seek the MAGIS – the more – for the greater glory of God. Dr. Ward speaks of “disruptive gestures that authenticate the terms of engagement we use in the contact/combat zones of literary and cultural enterprises.” To invite students, teachers, and parents to sit side-by-side constituted a “disruptive gesture” to the existing pedagogical and cultural paradigms. That disruption also provided a bit of inspiration for one of my students, Arianna Valderamma, as she created a website devoted to young black readers. In addition to reviewing novels on this site, Ari also noted when publishers of novels with protagonists of color misrepresented by depicting white children on their covers, ostensibly eliding blackness in their marketing efforts. She currently writes for The Millions, “an online magazine offering coverage on books, arts, and culture since 2003.”

Writing with an even more contemporary focus – and through the prism of Fannie Lou Hamer’s 1964 speech — Dr. Patrick Alexander provides the view from within Dr. Ward’s historical milieu into the lives of those whose subject positions ally them to Ms. Hamer. Here, I construct a parallel comprised of Dr. Ward’s “disruptive gesture” and Dr. Alexander’s “oppositional speech.” The former signifies HBW’s most important reason or purpose for existence: “to be in the forefront of research and inclusion efforts, committing to literary recovery work in Black studies, textual scholarship, professional development, and cultural literacy studies.” A tall order, this is.

The UM Prison-to-College Pipeline Program/”The Parchman Project” with Dr. Alexander on the left.

Dr. Alexander’s “oppositional speech” resonates – especially today – with the growing grassroots activism we have seen among women across the globe assembling and marching soon after the last presidential election, Florida high school students unwilling to accept that their elected officials will do nothing to address gun violence in schools, to the most recent teacher walk-outs and strikes across four states, but is set squarely in lives of those enduring the “Panopticon of Parchman Prison.” Though the setting of Dr. Alexander’s focus appears to be very different than that of HBW, his work riffs on The Project’s goal to widen the circle, to deepen our associations WITH black writing and to expand the definitions that, like the panopticon, limit what those on the periphery can see. The Parchman Project and the HBW project then, become as ripples in a pond, expanding outward and encompassing new venues, new platforms, new constituencies in the quest to promulgate an understanding of and an appreciation for Black Writing.