GOOD OMENS FOR SCHOLARSHIP

The MLA Handbook, Eighth Edition (2016), bids us to consider the probability of having a single “set of guidelines, which writers can apply to any type of source” (Handbook, rear cover). This new edition may be less intimidating than the Seventh or the Sixth, and it may minimize anxiety about scrupulous documentation in the age of the digital. Nevertheless, we should not put older editions of the Handbook out to pasture, because the new one seems more a supplement than a replacement. It lacks the solid advice about research and writing we found in Chapter 1 of the Seventh, and not all of us want to visit The MLA Style Center, the open access online companion. Neither in documentation nor in the vast range of scholarship is it prudent to drift with the wind.

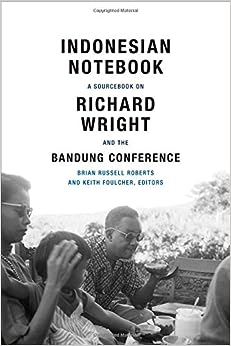

Indonesian Notebook: A Sourcebook on Richard Wright and the Bandung Conference (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), edited by Brian Russell Roberts and Keith Foulcher, is a good omen that scholars who refuse to get lost in the brothels and mazes of theory-whipping can be productive long-distance runners. Roberts and Foulcher have used impeccable literary historical scholarship in producing a book that maps new territory for studies of Richard Wright’s life, works, and prophetic acumen. Indonesian Notebook is exceptionally valuable for anyone, including political scientists and historians, who is interested in what world literature created during the Cold War period actually challenges us to interpret.

When we truly revisit Wright’s The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference (1956), armed with the generous amount of contextualizing matter that Roberts and Foulcher translated from the Indonesian, we are stimulated to ask just what did Wright see and hear at the conference and during his conversations with Indonesian intellectuals. What inspired Wright to quite accurately speculate that the world of 1955 was a crucible for multiple forms of terrorism rooted in religion? And what did Wright reveal in his lecture “The Artist and His Problems” (published as “Seniman dan Masalaahnja” in Indonesia Raya on May 22, 1955) that might have informed his decisions about what essays to include in White Man, Listen! (1957)? The winding path of scholarship may take us to Ethan Michaeli’s The Defender: How the Legendary Black Newspaper Changed America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016) to discover why John Sengstacke assigned Ethel Payne to cover Bandung for the Chicago Defender and to James McGrath Morris’s Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press (New York: Amistad, 2015) for a choice bit of information about how the U.S. government used CIA funds to enable Payne and Wright to attend an Asian-African conference. I shall soon write at greater length about Indonesian Notebook which, as Amritjit Singh aptly remarks, “reminds us that the quest for equality must confront the stubborn local socio-economic realities throughout the globe” (Indonesian Notebook, rear cover blurb), because I do want to confront the stubborn actualities of political designs and literary meanings. Fortunately, there is no single set of guidelines for that task.