The Gifts of Black Prisoners

Just as DuBois’s The Gifts of Black Folk (1924) is overshadowed by The Souls of Black Folk (1903), the long shadows of our classic slave narratives obscure the importance of studying other autobiographical forms in efforts to write more expansive histories of how African Americans have used literary and literature or black writing in English since the 18th century. Accidental “discoveries” of lost materials are special moments in the growth of scholarship, enabling us to enlarge the body of black writing and to conduct archival projects to refocus our perspectives. Julie Bosman’s article Prison Memoir of a Black Man in the 1850s-NYTimes.com notifies us that a special moment is in the offing.

Just as DuBois’s The Gifts of Black Folk (1924) is overshadowed by The Souls of Black Folk (1903), the long shadows of our classic slave narratives obscure the importance of studying other autobiographical forms in efforts to write more expansive histories of how African Americans have used literary and literature or black writing in English since the 18th century. Accidental “discoveries” of lost materials are special moments in the growth of scholarship, enabling us to enlarge the body of black writing and to conduct archival projects to refocus our perspectives. Julie Bosman’s article Prison Memoir of a Black Man in the 1850s-NYTimes.com notifies us that a special moment is in the offing.

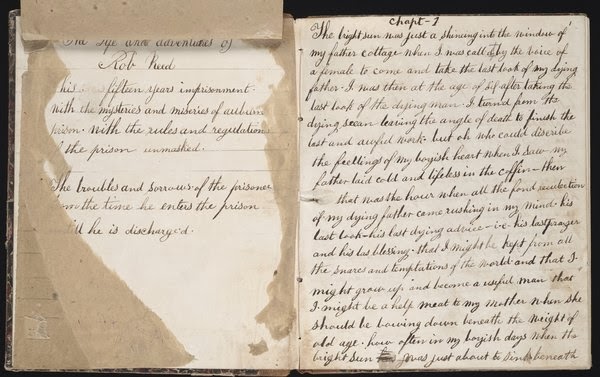

The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library’s acquisition of Austin Reed’s “The Life and Adventures of a Haunted Convict, or the Inmate of a Gloomy Prison,” dated 1858, is a great find if the memoir is indeed authentic and not a parody written by a white prisoner or white prison guard in the 1850’s by a person who wished to exploit the popularity of slave narratives. We do not need yet another example of bogus black writing. We are still in a state of uncertainty about whether Hannah Craft’s The Bondwoman’s Narrative is truly what we have been told it is. We do need a 19th century bit of prison writing that is beyond dispute, that can be analyzed in some framework of African American autobiography and set against the literary/non-literary qualities of, let us say, George Jackson’s Blood in My Eye and Soledad Brother: The Prisoner Letters of George Jackson and other writings by the imprisoned (e.g. the early poetry of Etheridge Knight). It is better to err in the direction of extreme skepticism than to be duped.

Contemporary literary and cultural studies often play deadly games with African American intellectual property, and I think it is prudent for the Project on the History of Black Writing to issue a caution regarding what Bosman described as “the first recovered memoir written in prison by an African-American.” Thus, I sent the following e-mail to Professor Caleb Smith:

As a member of the Project on the History of Black Writing advisory board, I was pleased to read in today’s New York Times that you will prepare Austin Reeds manuscript for publication. This project extends, and perhaps deepens, your previous studies of incarceration. I am confident you will provide judicious contextualization for our analysis and interpretation of the memoir. Those of us who have special interest in African American literacy and literature welcome the challenge of dealing with the literary and non-literary aspects of “recovered” works. This example of 19th century prison writing raises questions about autobiography in general and African American autobiography in particular and about how the genre functions in a multi-layered national literature.

I do hope that Christine McKay and others used the most exacting scientific principles in establishing the authenticity of the memoir for the Beinecke. What we do not need is to discover, after publication, that the memoir is a devastatingly clever imitation of 19th century black writing. Use of the most rigorous standards of authentication and bibliographic or textual scholarship must provide the evidence that inspires confidence.

Please accept my thanks for your helping us to create more precise literary histories of African American writing.

Sincerely yours,

Jerry W. Ward, Jr.

Distinguished Overseas Professor

Central China Normal University (Wuhan)

Professor Smith graciously answered within a few hours, assuring me that “The Reed manuscript really is a haunting text. We have worked very hard to piece together the facts of Reed’s life and the circumstances of his writing. I expect that the publication will be just the beginning of a long conversation.” (Email from Smith to Ward, December 12, 2013) We should anticipate that the “long conversation” will give birth to a rich discourse about genres, the possibility of deconstructing incarceration as enslavement in American historical contexts, canons, and the aims of scholarship inside and beyond the fragile boundaries of American higher education. We may, dispute ourselves, be once more enlightened by the gifts of black prisoners and by the assertions of Americans who do not know the kinship they share with the imprisoned.