This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

Fight Media Hegemony with a Trickster’s Critique: Ishmael Reed’s Faction about O.J. and Media Lynching

Editor’s Note: The Project HBW Blog mostly traffics in shorter pieces, but from time to time we like to present our readers with a longer piece, as well, in a feature we call Taking the Long View. For this installment, we feature scholar Yuqing Lin’s insightful, challenging review of Ishmael Reed’s recent novel Juice! Thanks to HBW Lead Blogger Dr. Jerry W. Ward, Jr., for passing along this piece of scholarship.

Ishmael Reed’s new novel Juice! (2011) focuses on the American media and, dissecting their exploitation of the O.J. Simpson criminal trial, its manipulation of public consciousness. By tracking years of news and commentaries in media, Reed shows the segregated media’s sick obsession with O. J. and the black male image, and uncovers the hypocrisy of “post-race” racial politics. Under his scrutiny, the reader finds that with the social climate turning right and more conservative, media discourse is becoming more totalitarian under corporate operation. Reed dissolves the traditional novel plot and juxtaposes reality and imagination by using news clips, cartoons, scientific documents, and court transcripts. The novel includes both human and animal characters connecting Reed’s work to thousands of years of North American storytelling. Reed’s grandmother on his father’s side was a Cherokee Indian. He constructs a narrative space to question the segregated media’s bias and racism.

As a postmodern novelist, Ishmael Reed views American mainstream historical and political discourse from a different stance. Starting from the 1960s, he has written novels, poetry and essays that challenge white critics, black nationalists, radical feminists and many other sects. From the early 1980s, he has written under the doctrine of “writin’ is fightin” and has become, after spending thirty years living in the kind of ghetto in which he grew up, a more radical social and media critic. He has evolved from the early experimental style of The Free-Lance Pallbearers and Mumbo Jumbo to an original postmodern realism, combining fiction with social-political reality. From The Terrible Twos, the targets of his critiques have involved more political corruption, social crisis, and media bullying. As someone who has played with genres again and again, including sonnets and ballads, he described his The Terrible Twos as a post modernist social realist novel. Except for the late critic, John Leonard, writing in The New York Times, that he was as close as American literature was to get to Gabriel Marquez, the novel, which took on the Age of Reagan, and predicted the period of selfishness, and homelessness of millions that would follow, received a chilly response from American critics.

His books of essays, Mixing It Up: Taking on the Media Bullies and Other Reflections and Barack Obama and the Jim Crow Media or the Return of the “Nigger Breakers,” heavily target media’s hegemony, especially television from which most Americans receive their information. For him, television and Hollywood are the most powerful instruments of mind control yet devised, which, in the United States, are used to raise lynch mobs on unpopular groups, especially black men. While the American media criticize the media of other countries for being under the control of the state, the American media are controlled by corporations, which is why criminal activities of big corporations, the banks, the pharmaceutical companies, and Wall Street are rarely covered while the petty crimes of the poor are featured. When the black Attorney General Eric Holder was asked by Senator Elizabeth Warren why no bankers had gone to jail as a result of their laundering drug money, he said that it was because jailing these criminals would have a deleterious effect on the economy. Those few minorities who have jobs as pundits are there to blame social problems on the personal behavior of the poor, and when they depart from this assignment, they are forced to apologize, be suspended or fired. For Reed, they are little more than collaborators.

For his hard hitting books which criticize the American media, which he compares with the media of Nazi Germany for their ability to scapegoat minorities (Reed, 2012: 17), Reed’s books have been ignored by the American media or dismissed by those whom he calls “proxies,” while the literature that holds black men responsible for America’s social problems is promoted. Black cruelty to women is certainly an issue to be addressed in literature, but since women from other ethnic groups seem reluctant or afraid to criticize patriarchal control of their communities, and because white corporate feminists are dependent upon white men for power, black men have become symbols for male cruelty in the United States and abroad. This has resulted in what critic C. Leigh McInnis calls the Black Bogeyman genre, which he says “sells better than sex” (Reed, 2012: 22). This literature distracts from the crimes of corporations committed in the United States and abroad.

Juice! tells the story of African American cartoonist Paul Blessing, pen-named Bear, whose life is mingled with the life of O. J. Simpson. The story of Bear—a fictional character—and the news coverage of O. J. Simpson form two lines of narration which converge now and then. Reed pastes together the Simpson trials, the Oklahoma explosion, the Clinton scandal, the 9/11 terrorists’ attack, and the 2008 economic crisis in an anachronistic way. So the novel turns out to be more about a black male artist’s survival in the corporate media era. By embedding real history into fictional space, Reed enriches his decades-long fight against sects of cultural hegemony, exposing the hypocrisy of media and dominant racist discourse.

The reception of this novel in America has been mixed. On the one hand, the novel was praised as “a genuinely inventive novel, which depends not on people in catharsis but on the pleasures of the riffing itself” to mock the so-called post-race harmony (Domini). On the other hand, Paul Devlin, a regular contributor to theroot.com whose editor-in-chief is Henry Louis Gates, Jr., said in a review that “Reed’s tendency to go too far has not diminished,” which was later parodied by Reed into the title of his latest essay collection Going Too Far: Essays About America’s Nervous Breakdown (2012). Still some critics say Reed lost his sense of humor and wit so prevalent in Mumbo Jumbo, as “there is so little humor” and Reed is “hammering his audience under wordy gravel” (Wellington: 29). Some call it “grumpy” “rants” and take the O. J. Simpson murder case as the real subject of the novel (Coan). On the contrary, the focus of the book is not arguing for O.J. It is through the Simpson trial that Reed reviews how the mass media creates a myth of black “collective blame,” and how a stereotyped image of black males is penetrated into the public consciousness. Reed uses Simpson’s trial as the thread to uncover the impact of media hegemony on the profession of Bear—a black male artist.

The hegemonic discourse of racist media

Reed’s criticism of politics is more direct and harsher since the 1980s, when right-wing American politics became more conservative in the Reagan administration. According to Ben Bagdikian, the growth of the right-wing has had a deep impact on the fairness of U.S. government administration. Conservative think tanks, such as the Hoover Institution, The Heritage Foundation, and American Enterprise Institute are generated with far-right goals in mind, and the main news media is controlled by corporate capital(IX-X). The media changes the traditional social, political and legal construction and builds an image of the world sometimes independent of the real world.

The corporate-owned media is being commoditized, thus media as “the fourth power” is losing its objectiveness and instead functions as a whore after business benefit. According to the cultural hegemony theory of Gramsci, the mass media is to promote the dominant ideology and the discourse of power. The marginalized communities who have few resources are left silent in their press. As Reed points out, “the segregated American media with its alliance with the right wing and racist forces like the Tea Party movement which was created, organized, and amplified by the segregated Jim Crow media, are the most powerful opponents to black and Hispanic progress” (Reed, 2012: 182-83). Simpson’s trial was a typical case of “collective blame,” which was what model Naomi Campbell meant when she said “all black men were guilty by proxy” (19). The media started a bash against O. J. and those who are inferred to be behind him–African American males. “As long as African Americans are blamed collectively for the actions of an individual or a few, they aren’t free” (111). The same kind of bashing happened after the World Trade Center terrorist attack, when the main media turned its attention to “collectively blame” Islam and cast the “crimes of the few” upon Arabs and Arab Americans (231).

O. J. Simpson’s trial, the so-called “trial of the century” by the media, connected the whole society together. The biased reports of media aroused the tension between African Americans and the white population. What’s more, the media followed Simpson’s civil trial and then his every move; they started a “public lynching” out of court to turn O. J. into a “dancing monkey,” an entertainment for the masses (235). Reed takes the media’s prey on O. J. as a clue to investigate the racial tension behind the media carnival, and the psychological prosecution blacks face every day under media hegemony.

O. J.’s transformation from a hero to a “scapegoat” reflects the main culture’s control over the image of the black male. In their “decontextualized” environment, O. J. becomes the symbol of “blackness” in racial politics, more than an individual. In the racist discourse, white is the invisible social norm and blackness is the visible sign, existing as the opposite of whiteness. As a cultural sign, O. J. is made into commercial products—his body as a gold mine—“Not only are the television networks improving their ratings, but they’re selling t-shirt and O. J. games” (83). The media is termed by Reed as “Beasts with A Thousand Eyes,” “instead of preying upon human flesh, they prey upon our [black] image,” and “we’re the favorite meal. They’re fascinated with us. They can’t do without devouring and regurgitating us” (191).

With the arrival of digitalized society, human beings live in the web of discourse interactions. The general public is controlled by media infiltration and might gradually lose their individuality and critical ability under the hegemonic discourse of ruling power. When the murder occurred in Juice!, overwhelming media coverage dominates Bear’s life. He checks newspapers and TV to track every bit of information about the case. He is so obsessed that news reports become his junk food. “Beasts with A Thousand Eyes” infiltrate people’s everyday life and send prejudiced opinions through their reports. The media keep digging up more scandals in the black community, such as poverty, drug abuse, crime, and teenage pregnancy, to meet the white middle class craving. In KCAK(KKK) TV station where Bear works, the most popular program, “Nigguz News,” features black gangsters. Reed satirizes the news moguls such as Rupert Murdoch and his media empire. Just like television station KCAK, a formerly viewer-sponsored station, was taken over by big money. Changes are made to end the traditional left-wing programs and appeal to more advertisers and a middle class white audience.

In the era of digital media, people’s perception of the world relies heavily on media reports. Media discourse in specific socio-cultural context is created for specific purposes, by specific techniques, representing the special interests of certain powers. In the media world, what’s important is not the truth of the event, but how the event is represented. The mainstream journalistic reports, as narratives, are constructed by dominating ideology by the interactions of power discourse. Reed’s intention is not to argue for O. J.’s innocence, because the “truth” is still unknown. In fact, the American media are ignoring a claim by a serial killer, who was part of Nicole Simpson’s social circle at the time of the murder, that he committed the murder. The media have also ignored the charge of police misconduct in the Simpson case. As the author implies in the novel and his essays, the American media always side with the police and in the case of the invasion of Iraq supported the invasion, one of the biggest calamities in American history.

By viewing the uncertainty of the “truth,” Reed reminds readers of media bias and the remnants of racist ideas in American society. O. J. Simpson is punished, no matter if he is guilty or not, because “they won’t let O. J. go as long as he can be used to contain blacks” (74). Furious at the acquittal of O.J. by a jury that the media mistakenly cast as “all black” (it included one white and one Hispanic) the media supported all white juries in the civil case and in the conviction in the Las Vegas case, which resulted from what some might call an “entrapment.”

The novel dissolves the traditional story line to present the fragmented media narrative with case analysis and commentaries. The micro media reports penetrate into people’s everyday world. The audience gets to know the Simpson trial through a series of media reports; but the facts are dissected and assembled by the media’s control over information by ways of concealment, distortion and exaggeration, so the desired effect could work on the audience’s consciousness. Reed is looking for contradictions in the fragmented media reports, to critique and retell the historical event from a different perspective.

In the postmodern society, media, as an important part of the operating mechanism of the dominant power, forms a micro power-web with the government agencies, prisons, armies, and courts to restrain the “rebels.” By integrating the media narrative, Reed uncovers the racist bigotry of America via the Simpson trials. To deconstruct the hegemonic discourse of news media, the voices to the public should come from all sides, rather than be segregated or one-sided. The marginal communities should keep an eye on the media out of self-defense. Bear and his friends are always on the lookout for the information of the “enemies,” so they, unlike European Jews and the Roma, will know what is coming before the bombs drop.

Critical means to restate history

To resist the control of news media, Reed recounts the historical event from a critical perspective, integrating court testimonies, TV news report, journals and newspapers, cartoons and fictional narrative via the genre of “faction.” “Faction” is a term that writer Alex Haley used to explain the technique he used in the writing of his novel Roots, though Ishmael Reed has used the technique in his novels in 1960s, where he includes personalities like Richard Nixon who became president.

What makes this novel stand out is that Reed takes pains to track the history of almost 20 years around the O. J. trials, applying historical figures to contribute to his imaginative construction of history. One hard truth of this novel is that Reed names names when critiquing the celebrities who are still active in political, judicial and cultural areas, such as G. W. Bush, (called Boer by Bear and his friends) Rudy Giuliani, Gloria Allred and Marcia Clark. To introduce so many real people into the fiction is neither to vent one’s anger nor to increase historical authenticity and objectivity for reading experience. Reed means “to provide another side, another viewpoint,” to question the one-sided “truth,” and to look for the uncertainty behind the truth through fiction (Dick & Singh: 187). The marginal culture finds its own prestige by viewing history in different ways.

In fighting against media power, Bear and his friends organize into Rhinosphere, which censors the white media’s distortion of black images and fights back in the name of the African American community. It is a group of older black men who were active in New York in the 1960s. They keep up with the thinking and fighting spirit of the 60s East Village and support the “brothers” who are attacked by media (from Michael Tyson, Michael Jackson, Kobe Bryant, Clarence Thomas to O. J.).

In recounting the Rhinos’ fight, Reed embeds the history of Africans fighting white colonists. Other than their pens and papers, Rhinos have few means to resist white cultural hegemony and its capitals. They are like dwarfs facing giants, as “old men out of step with the New Order,” who refuse to submit (32). Rhinosphere, called “Zulu Nation,” refers to the Zulu warriors’ defense against colonist invasions from the 1830s to 1880s. Due to their backward weapons and obsolete war strategy, the Zulu Kingdom was defeated, but their unyielding struggle cast a huge blow on the colonists. The members of Rhinosphere inherit the warrior spirit of their ancestors, “trying to fend off change with spears, clubs, hand axes, javelins, halberds” (32). In the novel, the Rhinos’ fights point both to the past and the present. Reed borrowed the idea of the Rhino as a symbol of black males from Ted Joans, called the greatest Jazz poet of the 20th Century. Joans said that black men are like the Rhino who is galloping through the jungle, minding his own business when all of sudden he is being poached. An early title for the book was “Poaching 22.” Even though Rhinosphere collapses as did the Zulu Nation, the history of the Zulus signifies that the fighting spirit doesn’t die out. The Zulus may come back. It also indicates that the white/black binary position doesn’t work and that direct resistance isn’t necessarily the best way. Similarly, Bear, who once fought white media head-on at the risk of wrecking his family, now begins to acknowledge different opinions and allows for “difference.” He even doubts from time to time if he should go “post-race,” as promoted by the media.

It should be noted that Reed satirizes complete assimilation and opportunism in identity politics. One theme of “post-race” society is to transcend the blacks’ double consciousness, but the assimilative stance of transcending black/white boundaries in fact means “a cultural submission” (Wang: 69). The novel has many minority characters who fully identify with white authority and internalize racism, such as the Hispanic anchorwoman Raquel Torres, and the token black president Renaldo Louis.

For years, Bear supports O. J. against family and society pressure but finally he wins the establishment’s approval with a half-finished cartoon condemning O. J. and Bear takes the money and praise from the International Society of Cartoonists. He makes a deal with the main culture as well as “get by giving white folks the jump fake” (298). Bear uses the award ceremony as a chance to wedge into the dominant discourse, to express a voice different from what is heard in the official media. Quoting the late cartoonist David Levine, who worked for The New York Review of Books: “Caricature is a form of hopeful statement: I’m drawing this critical look at what you’re doing, and I hope that you will learn something from what I’m doing” (257). Bear praises O. J. as a trickster like those found in folklore tales, and Bear himself also uses tricksters’ ways to shake off media control and find his own voice.

Bear witnesses the social transition from the Civil Rights movement of the 60s to the “post-race” era, when the media, with the help of corporate capital, was evolving into a cultural monopoly. Those who control the means of communication decide the contents of communication and influence the social-political discourse and individual identification. Readers cannot tell whether O. J. was guilty or not, because both Reed’s fiction and the media’s narration cannot fully reduce the truth of the event. But the novel uses both facts and fiction to get rid of media egocentrism and provide another perspective of history.

The cartoon figure old Badger, Bear’s “alter ego,” comes into the real world and talks Bear into self-reflection. The early radical Attitude the Badger, the best representative for the underground culture, who is constantly pursued by hunters and their dogs, grumbling about the situation in a society dominated by “establishment and authority,” has been discarded in favor of Koots Badger, who is toothless and toned down so as not to alienate KCAK’s (KKK) targeted audience, “Angry White Males” (58). Under the pressure of KCAK getting TV high-rankings, Badger is turned into a “harmless crank and paranoid out of touch” (46). It might be like “Ishmael Reed” in “some obscure hole in California,” in a state of exile which generates a different perspective (252). Both Reed and the Badger don’t give up on dialogue with this world, still “badgering.”

In Japanese by Spring, Ishmael Reed himself, as a cross-the-border figure, appears in the fiction and has dialogues with fictional characters, which is a way of postmodern self-reflection, similar to what happens in a painter’s self-portrayal. But this author’s intrusion into the fiction was harshly criticized. This time Ishmael Reed slips into the text again, (252, 321) so Ishmael Reed/Bear/Bear’s character-Badger all appears in the same text. The three layers of existence break the traditional narrative’s limits and synthesize the real world where the writer Ishmael Reed lives, the aesthetic world of the arts and the intrinsic value of arts. Instead of calling Badger’s appearance “surreal” or “absurd,” by blurring the boundary between reality and artistic creation, the novel causes tension between historical truth and textual fiction and reflects the political reference of postmodern fictions.

Meanwhile, Reed reminds readers that the aesthetic world can’t get away from social-political existence. In order to leave the Simpson case behind, Bear gives up political cartooning and turns to scenic painting; but the Bronco at the corner of his painting shows that artists can’t break away from deep-seated ideological and political consciousness. Just like the World Trade Center attack and the Iraq war, O. J. has become part of American social existence which deserves serious consideration.

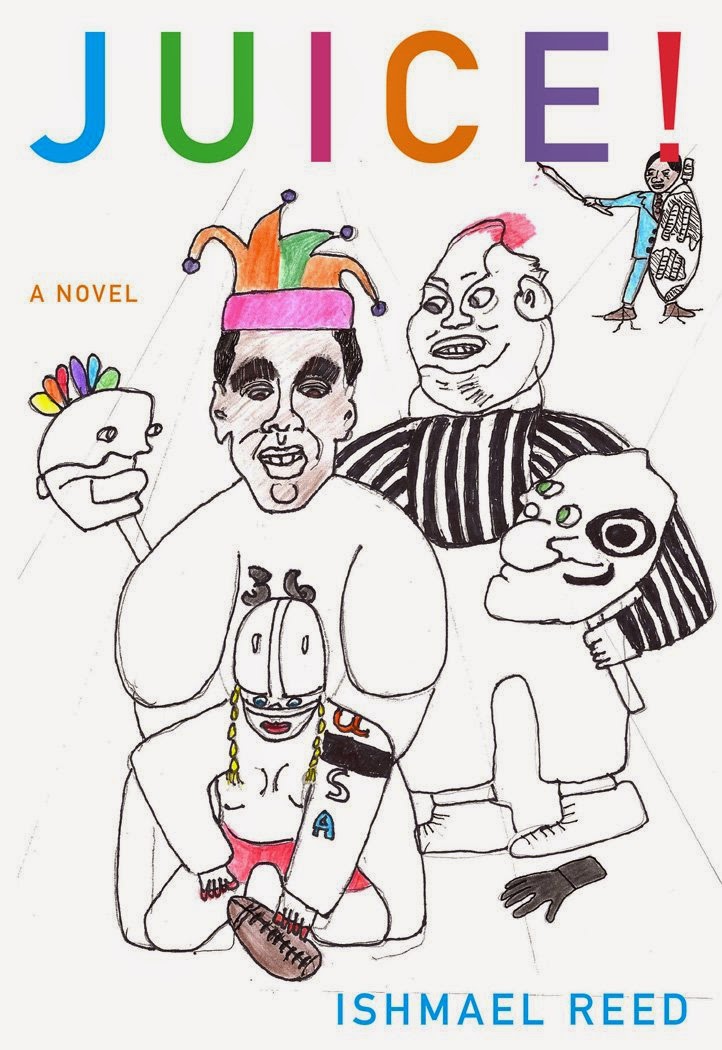

Reed’s writing captures the most-recent events, describes American mass culture and commercial culture in exaggeration, absurdity and contradictions and teases the hypocrisy and bigotry of news media representation. Juice! adopts hybridity and collage to challenge the traditional linear narrative, and it also uses cartoons and the official reports and documents on the O. J. criminal trial as subtext to form multiple layers of “factions,” and expose the tensions among different layers of existence. As an innovative artist, Reed claimed that “writing a conventional novel would be boring for me” (Reed, 2012: 177). The cartoons act as a parallel narrative including the cover drawing. The cover shows O.J. wearing a trickster/fool’s cap. He is about to receive a football from a blonde pigtailed woman, who symbolizes the USA. The number “36” was O. J.’s football number. The referee holds two sticks with faces on them. According to Reed, the faces are based upon the drawings of Chinese ghosts that he saw at an exhibit of Chinese drawings at New York’s Metropolitan Museum. One has the eye logo of CBS and the other wears the Peacock logo of NBC. In the upper right hand corner is a self-portrait of Reed holding a shield based upon an actual Zulu shield and instead of a sword, he holds a pen. Reed’s shoes are untied here, as presented in a classic Reed picture taken by Terence Byrnes. This cover cartoon was misinterpreted by KCAK feminists as O. J. sodomizing the USA, their excuse to indict the artist–Bear’s misogyny. It is Reed’s parody on feminists’ misreading him over the years, especially over Reckless Eyeballing (1986).

Juice! situates the media news reports and commentary in the fictional space of a novel, and connects the protagonist Bear’s life with O. J.’s. Reed breaks the official narrative and recombines the pieces, encouraging the readers to doubt the objectivity of media representation. As Reed writes in his essay, “the media are a segregated white-owned enterprise with billions of dollars at their disposal. Their revenue stream is based upon holding unpopular groups to scorn and ridicule” (Reed, 2010: 17). Reed takes it as a writer’s responsibility to censor media’s racist remarks, to work as “a one-man communication center” to check on “the propaganda attacks on besieged groups and individuals who don’t have the means to fight back” (Reed, 2010: 243). He is “the Fighter and the Writer,” as labeled by the Barbary Coast Award of San Francisco’s Cultural Festival. His writing career has been a fighting experience, reminding people to take a look at life critically, viewing history from a different stance.

References

1. Bagdikian, Ben H. The New Media Monopoly. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004.

2. Coan, Jim. “Review.” Library Journal. 2/15/2011, Vol. 136 Issue 3, p101-101.

3. Dick, Bruce, and Amritjit Singh. Conversations with Ishmael Reed. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 1995.

4. Domini, John. “Review”. http://www.bookforum.com/review/7411

5. Reed, Ishmael. Barack Obama and the Jim Crow Media: The Return of the Nigger Breakers. Montreal: Baraka Books, 2010.

6. —, Going Too Far: Essays About America’s Nervous Breakdown. Montreal: Baraka Books, 2012.

7. —, Juice! Champion: Dalkey Archive Press, 2011.

8. Wang, Liya. “Satirical Narration of Multiculturalism in Japanese by Spring.” Foreign Literature, 2010, Vol. 1, 67-75.

9. Wellington, Darryl Lorenzo. “Still Angry After Many Years”. Crisis, Summer 2011, Vol. 118 Issue 3, 27-29.