This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

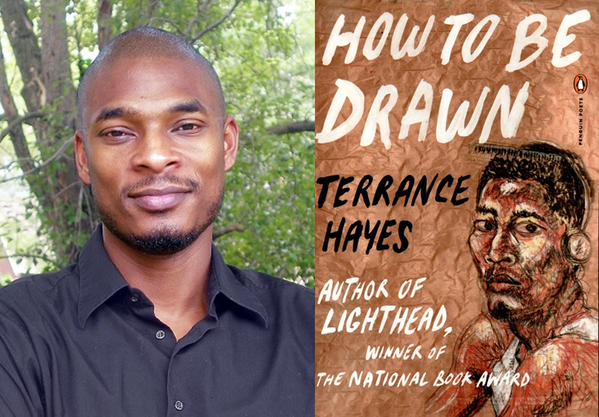

Drawing Terrance Hayes – Book Review

You could be drawn to the work of Terrance Hayes by way of Elizabeth Alexander’s advanced praise for How To Be Drawn, a statement that draws you to such words as dust, urgency, necessity, by any means necessary (the latter cluster evoking an injunction from Malcolm X); in addition, you could be drawn by noticing poems by Terrance Hayes are anthologized in Angles of Ascent as instances of “Second Wave, Post-1960s” but not in What I Say or The BreakBeat Poets, and the notice is a signal either that you are curious about where the cipher (a good Arabic zero) or that you do have non-trivial questions about inclusion/exclusion and probabilities/possibilities; it is better that you could be drawn by accessing http://terrancehayes.com/notes-drawn to find “notes, reference, and inspiration for the poems” in How To Be Drawn. Maximize your options.

Truth could tell itself by revealing that you are drawn initially by none of the above. You were drawn to the poems of Terrance Hayes by sustained interest in the innovative poetics of Asili Ya Nadhiri as manifested in his “tonal drawings.” The required proof is located at http://wp.me/p3kMgy-fj.

The device of ekphrasis may be one motivating link between the poems of Nadhiri and Hayes, because that device draws attention to how American poetry is a process which defies consensus. It motivates a few readers to think beyond the belief that “poetry” exists independent of a historicized reading and to ask whether poetry is actually or really necessary. Answers vary according to your choice of adverb —really or actually. A poem lacks a fixed definition of its identity. It does have descriptions. Thus, an imagined conversation between Hayes and Nadhiri is rewarding, because it begins to cast light on why some readers actually fear poetry while other readers so love poetry that they argue for the validity of any and every form that a poem can assume. The Republic of American Letters is becoming the Democracy of Writing in a slow hurry.

Truth also tells on itself when you access Terrance Hayes’s website to acquire the information needed for intelligent reading of the academic poems in How To Be Drawn. Hayes provides a most welcomed, common sense definition of what an academic poem is. When he answers the question “If you could be any tree, what would you be and why?” with a rich accident: “I’m trying to think of something clever here? I like the word magnolia. I like the smell of pinewood. I like the flowers of dogwoods. I’d be an apple tree.” The accident, for which Hayes is not responsible, is conjuring the relevance in the context of the question of Michael S. Harper’s remarkable Photographs: Negatives: History As Apple Tree (San Francisco: Scarab Press, 1972). The last five lines in Section 9 of Harper’s long poem are:

let it become my skeleton,

become my own myth:

my arm the historical branch,

my name the bruised fruit,

black human photograph: apple tree (n.p.)

Hayes made a good choice, as good as the choices he made of which poems to include in How To Be Drawn, which remarks to make in the Spring 2015 “Anything But Invisible” audio interview with Studio 360, and which forms to give “Black Confederate Ghost Story,” “How to Draw an Invisible Man,” “Portrait of Etheridge Knight in the Style of a Crime Report,” and “Reconstructed Reconstruction”—-poems I would recommend that my Chinese colleagues would teach in their American and African American literature courses. No. Those are my favorite poems. Good pedagogy requires that all the poems in How To Be Drawn should be taught, so that poems can themselves teach us something.

Navigating among works by Hayes and Nadhiri and all the poets who are in the most recent anthologies brings a jolt of recognition to people who have taught literature for several decades. Close reading and re-reading of texts are still worthwhile procedures as we transform dead print/drawings into vibrant literary events. But close reading now depends greatly, though not exclusively, on the use of the Internet, digital tools, and audio-visual information. New ways of “reading” give some credibility to the notion that a poem in the canon is not innately superior to a poem which is not so archived or museumed. Inclusion or exclusion seems to be a result of a poet’s having the “right” connections or a dynamite agent, having more than demitasse spoon of genuine talent, and having the blessings of fortune in an over-crowded market. You are indeed drawn in to be lessoned by the closing lines of Hayes’s poem “Ars Poetica For The Ones Like Us”——

Do not depend on speech to be felt.

Remember too that the eyes are not flesh,

That crisis is irritated by the absence of witness,

That Orpheus, in time, became nothing

But a lying-ass song

Sung for the woman he failed. (96)