This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

The College Language Association @ Chicago: A Place to Dream

Categories: HBW

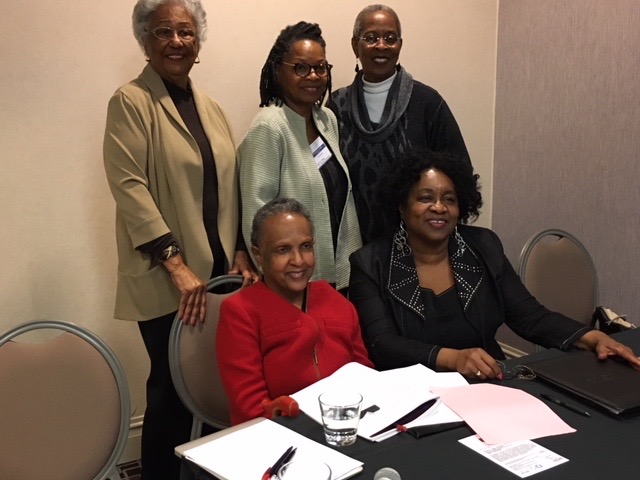

This year was my inaugural experience at the 78th Annual College Language Association convention. I was in constant awe—every panel I went to struck me as something new, expanding my horizons. But perhaps no panel stood at the center of the crossroads between scholarship and dynamic engagement with black literature and black history than the panel entitled “Chicago Dreamers: Literary and Life Legacies of a Migratory Magnet,” chaired by Dr. Daryl Cumber Dance with panelists Dr. Trudier Harris, Dr. Joanne V. Gabbin, Dr. Sandra Y. Govan, and poet Opal Moore.

I wanted to go to this panel because I have cited every single one of these undeniably powerful women in my own scholarship. Daryl Dance’s introduction outlined their incomparable achievements as she introduced the panel and invited anyone who wanted “to challenge or question” her claims to “meet [her] fellow panelists and [her] at the hotel bar tonight.” The women on this panel—founders and first participants of the Wintergreen Collective and the Furious Flower Poetry Conference among numerous other achievements—met in a crowded room on Friday, April 5th, to explore the full spectrum of what it means to be a Chicago dreamer.

I wanted to go to this panel because I have cited every single one of these undeniably powerful women in my own scholarship. Daryl Dance’s introduction outlined their incomparable achievements as she introduced the panel and invited anyone who wanted “to challenge or question” her claims to “meet [her] fellow panelists and [her] at the hotel bar tonight.” The women on this panel—founders and first participants of the Wintergreen Collective and the Furious Flower Poetry Conference among numerous other achievements—met in a crowded room on Friday, April 5th, to explore the full spectrum of what it means to be a Chicago dreamer.

Dr. Trudier Harris’s presentation centered on Lorraine Hansberry’s character Walter Lee younger from A Raisin in the Sun. Harris elucidated the importance of dreaming, arguing for Walter as a more engaging character than Richard Wright’s Bigger Thomas because Bigger “does nothing to make his dream of flying come true.” For Southern migrant Walter, dreaming is everything, and his dream of opening a business, Harris argued, touches the reader and/or audience on a deeper level because we understand Walter’s desires, his dreams of flying and his earnest sincerity in wanting to do so. Walter’s inability to hone his entrepreneurial skills leaves us with a question, one that Harris cited from Langston Hughes’s poem, “Harlem”: “What happens to a dream deferred?”

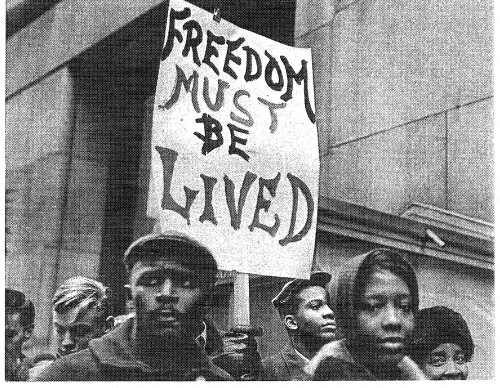

Activists in Chicago

Dr. Joanne V. Gabbin’s presentation was part-memoir, part educational coming-of-age story, as she described her education at the University of Chicago and the community of black scholars in Hyde Park that had a profound impact on her including George Kent, Val Gray Ward, and Don L. Lee who later became Haki Madhubuti. Like Dr. Trudier Harris, Dr. Gabbin’s presentation was about potential, a potential that she saw in herself and one that lead her along with others to fundamentally change Black studies at the University of Chicago and beyond. Gabbin emphasized the community that she found, a community that has changed over time but one that she has always felt she can return to.

The next panelist, Dr. Sandra Y. Govan, also told a story about personal development and fulfillment, but it was not her story; instead, she channeled her father, a Southern migrant who was forced to leave the South in fear of his life. Hopping a train to escape, he found a bastion of opportunity that was Chicago in the early 20th century, joining other family members who had arrived before him. Like Dr. Harris’s arguments for the importance of dreams and hope in the character of Walter Lee Younger, Dr. Govan’s story of her father’s perseverance in the face of danger demonstrates the importance of self-preservation and self-determination.

The final presentation by Opal Moore shifted the panel’s focus to a native daughter of Chicago—or, rather, the native daughter of Chicago. Moore’s lyrical presentation explored themes of hope, expectations, and dreams deferred in Gwendolyn Brooks’s work. In particular, Moore was inspired by pictures of the Mecca Building in Chicago, a building that Brooks herself wrote about. Like the Mecca Building itself, Moore argued, Brooks’s poetry contrasts light and dark while also exploring the emotional and psychological impact of housing disenfranchisement among Chicago’s black residents.

Rear, L to R: Daryl Dance, Opal Moore, Trudier Harris. Front: Sandra Govan, Joanne Gabbin

The presentations on the “Chicago Dreamers” panel were diverse in topic, theme, tone, and intent, but they had one commonality: the need for community. Harris’s discussion of Walter Lee Younger’s story in A Raisin in the Sun demonstrates the need for a loving community instead of focusing on self-serving motivations; Gabbin outlined a literary and scholastic legacy, a legacy that included scholars, professors, and classmates whose recognition of the need for deep and genuine mentorship propelled her forward as a student and Black studies as a discipline; Govan’s story took us beyond the academic, as her father’s unique story of migration and perseverance resonates for others in his time and today; Moore’s closing thoughts on the poetry of Gwendolyn Brooks highlights the complexities and shadowed hope that have and still do mark Chicago’s black communities. While some of the conversation focused on dreams deferred, in some cases loss, much of it was about achievement. Not surprisingly, once the panel ended the room erupted in applause. As I left the room, I, too, somehow felt that I had achieved something—that I had been in the right place, at the right time, a new though short-term migrant to Chicago, who could create my own dreams about dynamic and engaged scholarship as part of a community, and perhaps like these women, experience through it effusive and genuine joy.