This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

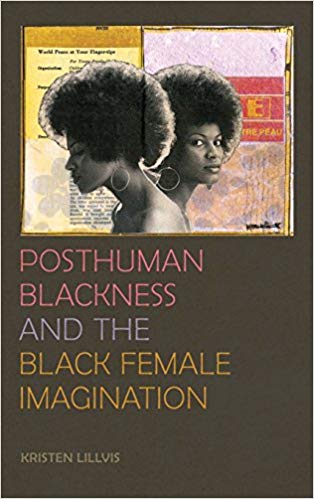

Book Review: Posthuman Blackness and the Black Female Imagination

Categories: HBW

University of Georgia Press, 2017.

Kristen Lillvis’s Posthuman Blackness and the Black Female Imagination explores posthumanism’s fusion of the body, flesh, gender and race through the works of various neo-slave narratives and contemporary performance artists. This “assemblage of ideas, material, and beings” speculates the future and positionality of the Black female imagination. Lillivis quotes bell hook’s definition of postmodern blackness as “the overall impact of postmodernism is that many other groups now share with black folks a sense of deep alienation, despair, uncertainty, loss of a sense of grounding even if it is not informed by shared circumstances” (2). Lillvis uses this definition as a major inspiration for her concept of posthuman Blackness and its intersections as she focuses on “the empowered subjectivities black women and men develop through their simultaneous existence within past, present, and future temporalities.”Lillvis gathers various works of women who write neo-slave narratives and situates the projection of Black futures as informed and liberated by these historical perspectives. She distinguishes between human and nonhuman, which is complicated by the Black posthuman subject who works to deterriotorialize that distinction through a multiplicity of being and becoming.

In the first chapter, Lillvis reviews liminity and temporality in Toni Morrison’s Beloved and A Mercy. She draws on Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s theory of becoming and hints at Jacques Lacan’s mirror stage when conceiving the posthuman subject as an ever-shifting being who is constantly reinterpreting liminal spaces.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari

In reviewing Beloved, the chapter probes the blurred lines between mother and daughter in Sethe’s relationship Beloved. Chapter two discusses posthuman subjectivity in Sherley Anne Williams’ novel Dessa Rose and nomadic subjectivity. Dessa Rose forms posthuman communities through connection to others and through the process of deterritorialization by disrupting hierarchal narratives. In chapter three, Lillvis defines Afrofuturism through the traditions of Mark Dery, Ytasha L. Womack, Kodwo Eshun, and Paul Gilroy, who are important theorists of the genre. While exploring more contemporary artists, like Erykah Badu and Janelle Monae, and their relationship to posthuman blackness, Lillvis argues that linking empowerment solely to history limits present and future conceptions of blackness. Chapter four details the idea of multiple consciousness in Octavia Butler’s science fiction. Centering Franz Fanon’s psychology of triple consciousness, the author questions black ontology, extraterrestriality, and how these concepts relate to posthuman consciousness. In the final chapter, Lillvis outlines the concept of submarine traversality in multiple texts by Sheree Renee Thomas and American film director Julie Dash. Glissant’s theory of submarine identity, Lillvis argues, serves as a precursor to post human subjectivity and liminality. A “prophetic vision of the past” allows the posthuman subject to embody transversal temporality in ways that creates new spaces for blackness to be and to become.

Lillvis is well versed in rhetorical theorist, tracing clear connection with posthumanity and materiality. Her nod to Deleuze and Gilles along with current terms in the field of rhetoric such as “assemblages” and “becoming” works well in exploring posthumaness. She references Lacan’s “l’hommelette” or “the human subject-to-be” that see themselves as a fixed entity, the posthuman subject “vibrates across and among an assemblage of semi-autonomous collectivities it knows it can never either be coextensive with nor altogether separate from.” Lillvis’ successfully positions posthuman identity as a form that is never fixed but is in constant becoming and interacting with multiple identities and communities in the process of transversing various modes of being. These theories apply to more contemporary artists like Erykah Badu, who uses temporal liminality to envision Black futures in her songs. Lillvis points out that Badu’s popular song “Next Lifetime,” set in 3000 A.D., as an example of posthuman becoming and temporal transfer.

Despite the useful content, Lillvis’ language density and repeated references overshadow her own voice and complicates her positionality as a white female scholar studying African American theory. Understanding that this is Lillvis’ first book, it explains the heavy reference to other scholars, creators, and their works. As she looks to establish herself in the field of Black speculative academia, she allows references to validate her stance. However, the driving force behind why she would be interested in the transversal subjectivity of posthuman individuals is a bit unclear. Though the use of “I” is discouraged in academic writing, her lack of argumentative statements conveniently leaves her own involvement outside of the conversation as she continuously points to the scholars of the discourse. The book reads like a well-researched, extended literature review, and the audience sees the process of her own questions of theories and research implications within the pages. She holds some of her own voice toward the end of the book when critiquing Black nihilism because she makes a distinction in separating the language of Western metaphysics and linear temporality from the spiraling complexities of posthuman Blackness.

Lillvis draws from her previous article to examine the somewhat closed connection between mothering and womanhood. In her article “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Slavery? The Problem and Promise of Mothering in Octavia E. Butler’s ‘Bloodchild,’”a title that is a riff on Hortense Spillers’ critique on oppressive systems in America, Lillvis explores Octavia Butler’s presentation of mothering as “a progressive force, allowing her marginalized characters—regardless of their sex—to destroy familial and communal hierarchies.” This is an interesting approach to opening the somewhat closed connection between mothering and womanhood, since this connection can be complicated due to liminality and temporality. However, transgender individuals and people who identify outside of the binary are not centered in this conversation of mothering. The word seems exclusive to individuals who “mother” outside of the gender binary. She makes a minimal references to LGBT individuals throughout the book. Primarily, since some trans people see themselves as types of cyborg (one who shifts and alters their gender, identity, and sometimes bodies in ways that the normalized binary society does not), I would argue that the conversation should center more transgender activists and scholars whose voices could add significantly to the discourse on posthumanism. Even though Lillvis opens mothering to men and women, this view is still binarist at its core that does not engage with individuals how are in the throws of posthumanism. ways that exclude non-nuclear ways of creating families and mothering, especially from a trans perspective. Janet Mock, a well-known transgender activist and writer, stated, “Becoming is the action that births our womanhood, rather than passive act of being born (an act none of us has a choice in). This short, powerful statement assured me that I have the freedom, in spite of and because of my birth, body, race, gender expectations, and economic resources, to define myself for myself and for others.” Mock speaks to posthumaness and transversality by coupling the process of “becoming” with womanhood, revealing a deep relationship with with body and economic dictates on identity.

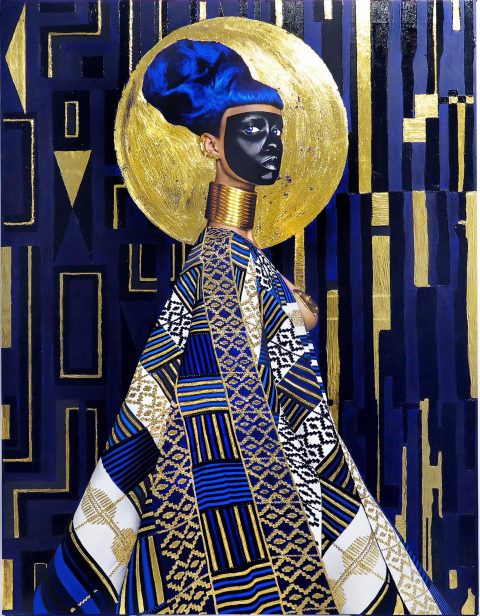

“Syzygy” by Lina Iris Viktor.

Lillvis leads the disscussion of Beloved with Paul D’s focus on connecting the past into the future. This focus doesn’t seem to fit well into the woman-centered narrative that the book epouses. Lillvis’ exclusion of Baby Suggs from the Beloved discussion leads the reader to question her interpretation of generational influences on posthumanism and transversality. She only mentions Baby Suggs in comparison to Paul D’s vision of nonlinear views of identity and time. She emphasizes Baby Suggs’ name, and how the infantalization of the word “baby” further complicates the adult/child divide. However, there is so much to discuss when it comes to Baby Suggs role as the mother and healer of the community, as the one who understands the disembodied spirit of the dead baby, and as “the unchurched preacher, one who visited pulpits and opened her great heart to those who could use it.”

Posthuman Blackness and the Black Female Imagination promises a wide examination of future-oriented visions of black subjectivity across various works by Black women. However, it fails in making coherent, unified connections between the contemporary artists and authors explored. Although Lillvis presents understandable applications of posthuman theory, the theories do not act as a congealing force throughout the chapters of the work, especially when it comes to surveying the Black female imagination. The book, however, is a great resource for scholarship in the field of Afrofuturism, although it does not add a voice of its own to the ongoing conversation of posthuman Blackness.