This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

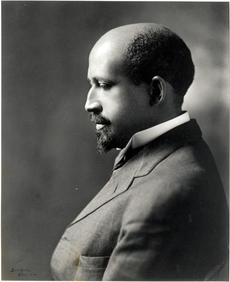

A Blues Moment in Dusk of Dawn: A Note on Autobiography

W. E. B. DuBois’s writing in The Souls of Black Folk (1901) is spiritual, and Dusk of Dawn (1940) complements the first installment of his autobiographical project with a secular sorrow song, with the blues. Despite the magnification of difference between Booker T. Washington and DuBois, it is refreshing to know that DuBois admitted his kinship and parallelism with Washington in the matter of miscalculating a solution for the problems of black folk. In Dusk of Dawn, Chapter 7, “The Colored World Within,” DuBois frees the cat from the bag. A truth scampers out.

W. E. B. DuBois’s writing in The Souls of Black Folk (1901) is spiritual, and Dusk of Dawn (1940) complements the first installment of his autobiographical project with a secular sorrow song, with the blues. Despite the magnification of difference between Booker T. Washington and DuBois, it is refreshing to know that DuBois admitted his kinship and parallelism with Washington in the matter of miscalculating a solution for the problems of black folk. In Dusk of Dawn, Chapter 7, “The Colored World Within,” DuBois frees the cat from the bag. A truth scampers out.

Here in the past we have easily landed into a morass of criticism, without faith in the ability of American Negroes to extricate themselves from their present plight. Our former panacea emphasized by Booker T. Washington was flight of class from mass in wealth with the idea of escaping the masses or ruling the masses through power placed by white capitalists into the hands of those with larger income. My own panacea of earlier days was flight of class from mass through the development of a Talented Tenth; but the power of this aristocracy of talent was to lie in its knowledge and character and not in its wealth. The problem which I did not then attack was that of leadership and authority within the group, which by implication left controls to wealth — a contingency of which I never dreamed. But now the whole economic trend of the world has changed. That mass and class must unite for the world’s salvation is clear. We, who have had least class differentiation in wealth, can follow in the new trend and indeed lead it.

Does one respond to DuBois’s idealism with a mixtape of Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come” and Gil Scott Heron’s “Home is Where the Hatred Is”? It may be better to up the ante of ambivalence by reading Andrew Zimmerman’s “Booker T. Washington, Tuskegee Institute and the German Empire: Race and Cotton in the Black Atlantic.” GHI Bulletin No. 43 (Fall 2008):9-20, the coat-pulling essay Gregory Rutledge brought to my attention. Washington by way of a practical enterprise and DuBois by virtue of his German education came to unfortunate conclusions in the danger zone of global capitalism. They ultimately had to pay the piper of grand designs. DuBois lived long enough to recant; Washington died too soon to make amends.

The blues moment does not eradicate our ambivalence, but it retards our temptation to settle for hasty conclusions about leadership. We check ourselves by reading what Robert J. Norrell says about Washington and Africa in Up from History: The Life of Booker T. Washington (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009). We reread DuBois’s The World and Africa (1946) with greater skepticism. We ask what is leadership to us. A panacea is a mirage, and DuBois’s blues epiphany confirms that the unity of mass and class is an impossible dream, that salvation cannot materialize.