This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

BlacKkKlansman: Talking Black, Paying Forward

[By: Danyelle M. Greene]

[By: Danyelle M. Greene]

In mid-August, BlacKkKlansman was released in theaters. Its subject is the “crazy, outrageous, incredible, true story” of Ron Stallworth’s undercover work as the first Black member of the Ku Klux Klan. The film linked racist imagery in early American films to a detective case from the 1970’s and news coverage of racial violence today. The work that this film does in order to give its audience a glimpse into history and a brief education in mediated imagery resonates with W. E. B. DuBois’s statement in his 1926 essay, “Criterion of Negro Art”, that “all art is propaganda and ever must be.” The part of DuBois’s statement that insists art be fundamentally obligated to continue as propaganda speaks not only to the nature of art as culturally influenced and influential. It also speaks to the work that Black artists have done intentionally or unintentionally to disrupt or reinforce dominant imaginations.

BlacKkKlansman’s dive into film history begins with a narrated montage of images from films such as The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Gone With the Wind (1940). These films, which drip with racist propaganda and stereotypes, are widely heralded in film history for their impressive narrative feats and technological innovation. Both films are considered American classics. As such, they dictate to their audiences the “ideal” culture of American society according to a national narrative that views whiteness as primary. In contrast, written and produced by black directors such as Oscar Micheaux, race films of the early twentieth century sought to entertain through stories of African American life and to counteract the violent, degrading images of the monolithic Hollywood Black character. Race films sought to resist those Hollywood films by presenting clashes between propaganda and the vision of Black artists, who were wrestling to overcome the prevailing images in the classics. Most notably, BlacKkKlansman references the political significance of mid-twentieth century film history with a cameo by Harry Belafonte, who sits in a room filled to capacity with young Black activists listening attentively to his childhood recollection of a lynching. As a historical figure, Belafonte is iconic not only for his activist work during and after the Civil Rights Movement but also for his acting, which cannot be separated from the work that he did off screen.

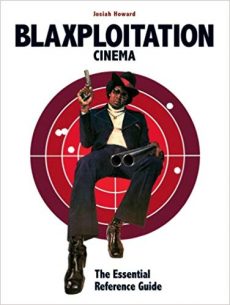

BlacKkKlansman also pays homage to the Blaxploitation films of the 70s with a dialogue sequence between Ron Stallworth and Patrice Dumas, president of the Black Student Union and his love interest. As they walk along a sunlit bridge debating the exploitative aspects of Blaxploitation film, the audience is offered a brief introduction to the discourse surrounding the production and reception of the genre. The movie posters of Superfly, Shaft, Coffy and others fill the frame as Ron and Patrice argue back and forth about the caricatures that permeated these films and the smooth crime-fighting men and women from that era. Emerging out of a time period of the Black Arts and Black Power Movements, Blaxploitation films sought to give audiences stories of the Black man winning, finally defeating the (white) Man—even if only for a brief moment—but at the risk of promoting age-old stereotypes.

The clear direction of BlacKkKlansman and its general message point to the strong influence of its creators and their convictions as artists, especially director Spike Lee, co-writer Kevin Willmott and executive producer Jordan Peele. The film is always already connected to and comments on a history of monolithic imagery of African Americans. The Contented Slave, The Wretched Freeman, The Comic Negro, The Brute Negro, The Tragic Mulatto, The Local Color Negro, and The Exotic Primitive are the caricatures Black artists must continue to contend with for themselves and for their work. These seven stereotypes that Sterling A. Brown identified in his classic 1933 essay, “Negro Characters as Seen by White Authors,” seem to have a permanent place in the national imaginary. BlacKkKlansman is situated within this cultural context as it presents Stallworth’s story. It is the story of an educated, motivated Black man, pushing back against the prejudices held by his fellow officers and the violence of the Klan.

The story is one of struggle, triumph, and regression as Stallworth climbs up the “racial mountain,” which Langston Hughes articulated, only to be pushed back down. In the final moments of the film, the investigation into the Klan is ordered to cease with all documents to be destroyed. Then, the Klan burns a cross outside the window of Stallworth’s apartment. Finally, Lee ends the film with a montage of footage from the 2017 rally in Charlottesville, Virginia that ended in the murder of Heather Heyer. Although the majority of the film references the relatively distant past, this ending reminds of the dangerous present that does not appear to be considerably different.

Danyelle Greene is a PhD student in the Department of Film and Media Studies at the University of Kansas. Her research focuses on the politics of representation in cinema for African Americans at the intersections of race, gender, and religion. She earned her MA in Media Theory and Research from Southern Illinois University Carbondale and her BA in Communication Arts and Sciences from Adrian College.