This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

A Black Humanist Theology: Reading Toni Morrison

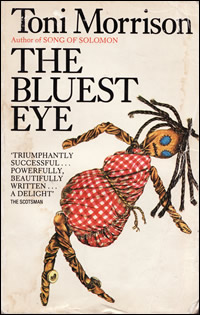

My research interest in philosophy and literature- more specifically, Existentialism, has continuously led me to the works of Toni Morrison. And while Morrison’s works need no justification—philosophical or literary—they present an opportunity to consider how the history of oppression can afflict a group of people, both past and present. The Bluest Eye presents the most compelling response to the question Dubois raised nearly a century ago: “What Meaneth Black Suffering”?

My research interest in philosophy and literature- more specifically, Existentialism, has continuously led me to the works of Toni Morrison. And while Morrison’s works need no justification—philosophical or literary—they present an opportunity to consider how the history of oppression can afflict a group of people, both past and present. The Bluest Eye presents the most compelling response to the question Dubois raised nearly a century ago: “What Meaneth Black Suffering”?

Precisely, Morrison’s novel is a question of “theodicy”—understood as the question of God’s justice in the presence of human suffering. In her fictional world, God is not limited to the traditional Western notion of the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. Instead, the concept of God must compete with the existence of evil and narratives of suffering and affliction in the face of a faith tradition that preaches the omnipotence of a just God.

By far, Pecola Breedlove, the protagonist in The Bluest Eye, is the one character whose life seems most vulnerable to those who have bought in to Western ideals. When Pecola encounters Geraldine—a black woman who tried to suppress her racial identity by getting rid of “the dreadful funkiness of passion, the funkiness of nature, the funkiness of the wide range of human emotions”, she is treated not only as a nuisance but as a very threat to the “sanitized” world she has created around her son. When Pecola is thrown out of Geraldine’s house, she sees a portrait of a White Jesus “looking down at her with sad and unsurprised eyes” (76). It is an image of a God who seems incapable of assisting her or a God who is complicit in her suffering. With this portrait of Jesus, Morrison brings to the forefront the shortcomings of a Western model of God that is supposedly loving and omnipotent, yet can allow the existence of evil and suffering. This image of God is quite inadequate for Morrison. For if God, as the theologian James Cone echoes, is not on the side of the oppressed “then we had better kill him”.

The ghost of Baldwin haunts us all. In the midst of American terrorism, he raised the most important question of the century: What does it mean to be human? Precisely, the black religious experience is about being and becoming more human under God. Morrison’s works suggest that Western theology have lost its connection to the fundamental link between God and humanity. After all, if one’s humanity is inextricably linked to God, it would follow that God cannot be fully God, without also being in solidarity with those who are/ have been most marginalized.