Awards, Legibility, and Contemporary African American Poets

In the age of social media, National Poetry Month spawns a proliferation of catalogs to the effect of this sample: “30 Poets You Should Be Reading.” Recent years have seen these lists become more diverse and reflective of the range of incredible contemporary American poets. (The collaboration between poets and designers from The Washington Post does relatively well at this.) And the array of race- and gender-centered controversies swirling in the poetry world throughout the past twelve months has resulted in special attention this year to ensuring that this month-long celebration be attentive to those who remain marginalized in American poetry

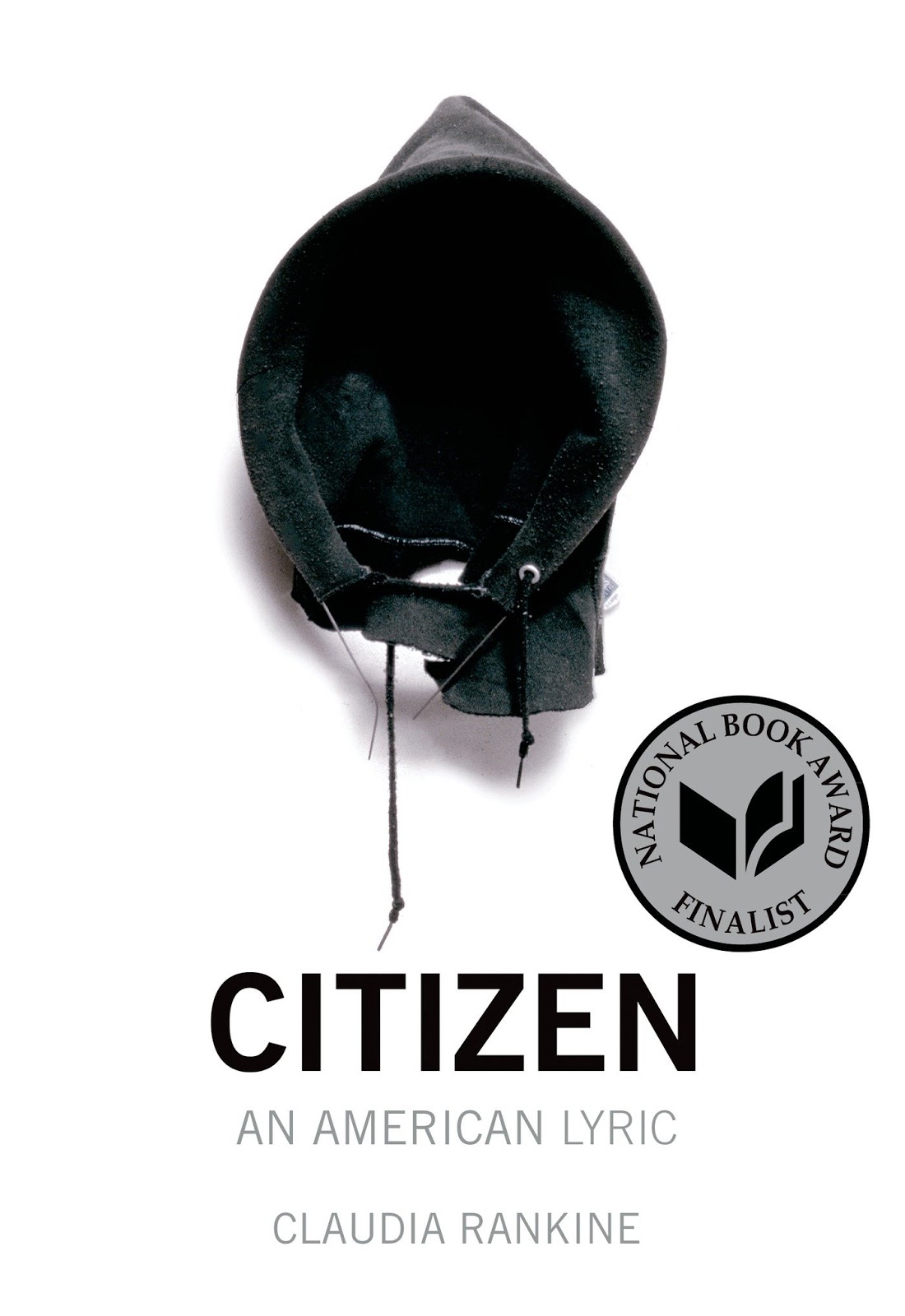

Thus it is unsurprising to see black female poet Claudia Rankine’s name on just about every one of these lists of recommendations this year, in light of how enormously her 2014 text Citizen: An American Lyric (Graywolf Press) exploded in success throughout and after the 2015 literary awards season. Citizen, which now has at least 200,000 copies in print—no small feat for any contemporary poet, let alone one who has not yet received a Pulitzer—won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in Poetry, the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work in Poetry, and the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry, among other honors, and it reached the #15 spot on the New York Times bestseller list in the “Paperback Nonfiction” category. That the work merits such laud and has usefully invigorated many poetic conversations. (See the excellent Los Angeles Review of Books two-part symposium on the book earlier this year at Reconsidering Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric. A Symposium, Part I and Reconsidering Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric. A Symposium, Part II.)

Nevertheless, it can be disheartening to see the significant impact that awards have on shaping those lists of poets recommended to the public, both during National Poetry Month explicitly and throughout the rest of the year implicitly (via reviews, syllabi, and so forth). While progress is certainly being made toward diversifying everyday conceptions of American poetry, with more and more African American poets garnering those major awards that increase their visibility—as documented by Howard Rambsy II on his phenomenal blog (A Local Conscious Poet who knows a lot about Prince)—it is vital that we pay close attention to what types of texts aesthetically and thematically receive that increase in support. Learn more about the progress at Reginald Harris & Phillip B. Williams: Witnessing lost boys & men. Learn more about the major awards at Black Women, Poetry, Awards & Fellowships, 1975-2015.

Using Rankine’s text as an example, it is interesting to note how Citizen differs in scope from her preceding collection, the also astonishing and identically subtitled Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric (Graywolf Press, 2004) that focused significantly more on global, diasporic blackness. While both of these paired texts address the grievous instances of violence committed against black bodies in late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century United States, the transnational view and sense of global black solidarity is far more pronounced in the earlier text. Unlike Citizen’s highlighting of a composite lyricized first-person self, the fragmented first-person voice in Don’t Let Me Be Lonely often provides global context for the events it narrates, emphasizing the racism and discrimination inherent in: U.S. attitudes toward the crisis in South Africa regarding the distribution of HIV/AIDS medication; the American role in the Israel-Palestine conflict; and the imperialistic implications of post-9/11 American global intervention.

This could be just a passing observation about distinctions between an important poet’s two most recent collections—were it not for the fact that awards generally seem to favor texts by black poets that do not explicitly discuss global black solidarity. As just one other example, Tracy K. Smith’s Life on Mars (Graywolf Press 2011), winner of the Pulitzer Prize, is distinctly less diasporic and international than was her preceding collection Duende (Graywolf Press, 2007); those short sections that do explore international events were repeatedly criticized in reviews.

Overall, we must be careful to scrutinize what types of aesthetics awards committees are choosing to honor: Rankine certainly deserves the attention she is receiving, and the four African American poets who have won the Pulitzer (Rita Dove, Yusef Komunyakaa, Natasha Trethewey, and Smith) have crafted meaningful bodies of work that merit wide readership and scholarly discussion. But we must be cautious about letting the limited vision of awards juries dictate which types of black poetics dominate our conversations. While it is important to be aware of the unreasonable power of literary awards, though, we might also feel some optimism that the recent surge in attention to Rankine could motivate scholars and readers to look at the rest of her remarkable oeuvre—and that such awards might have similar effects for other African American poets who merit close reading across their careers, not only in moments of limelight.