This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

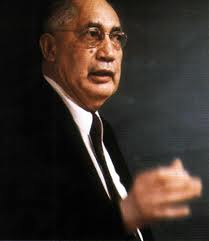

An Appreciation of Sterling A. Brown (1901-1989)

Categories: Guest Blogger, HBW

The outcome and aftermath of the recent presidential election have unleashed upon the world an enervating, extremist public discourse rooted in divisiveness, intolerance, and discord. In this language, the moral imperatives of civility, mutual respect, and common sense have been sacrificed to political cant and ethnocentrism. The politics of insincerity and expediency have become poor substitutes for compassion and statesmanship. Truth and reason have come under assault by “alternative facts” and irrationality. All of this begs the question Black feminist June Jordan raised in 1978: “Where is the love?” While many have answered Jordan’s query—including, among others, the richly symbolic Toni Morrison and Michael S. Harper and the more popular Terry McMillan and E. Lynn Harris—Sterling A. Brown* anticipates with unerring insight the concerns of today’s chorus of quite diverse voices.

Born 1 May 1901, Brown emerged in the 1930s and 1940s as one of the outstanding proponents of humanistic value in a day and time beset with Depression and World War. His astute insight into personal and cultural value addressed many of the concerns we wrestle with today: poverty, racism, diversity, inclusion, and more. Driving this engagement was an aesthetic vision he derived from the lives, language, and lore of Black folk. Without preaching or proselytizing, his innovative poetry and eloquent prose ushered us into an understanding of the extraordinary in ordinary life. He transformed the lives of Black vernacular speakers into models of wit, wisdom, and compassion. His art subtly revealed the hypocrisy, hatred, and difference that forced people into silos of racial and class separation. More importantly, his poetry provided a way out. It was an implicit guide to humanism, interracial communion, and more. This pursuit helped to sustain those qualities that made people human.

Born 1 May 1901, Brown emerged in the 1930s and 1940s as one of the outstanding proponents of humanistic value in a day and time beset with Depression and World War. His astute insight into personal and cultural value addressed many of the concerns we wrestle with today: poverty, racism, diversity, inclusion, and more. Driving this engagement was an aesthetic vision he derived from the lives, language, and lore of Black folk. Without preaching or proselytizing, his innovative poetry and eloquent prose ushered us into an understanding of the extraordinary in ordinary life. He transformed the lives of Black vernacular speakers into models of wit, wisdom, and compassion. His art subtly revealed the hypocrisy, hatred, and difference that forced people into silos of racial and class separation. More importantly, his poetry provided a way out. It was an implicit guide to humanism, interracial communion, and more. This pursuit helped to sustain those qualities that made people human.

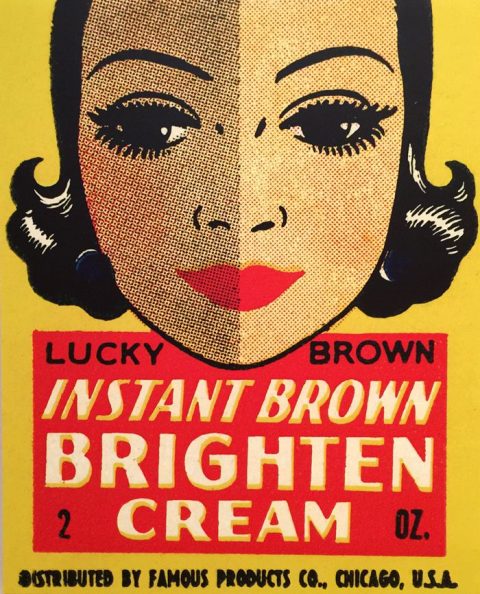

The legacy of “separate but equal,” from the infamous 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, survived in the white popular imagination and encouraged seven Black literary stereotypes in American literature. In prose that was both analytic and satiric, Brown challenged the illogic of these misrepresentations. For the 1920s and 1930s, Brown’s critical act was innovative. He was the first literary historian to explore the social necessity that formed the basis for these stereotypes. The “Brute Negro,” for example, resulted from the post-Reconstruction imperative used to justify the recreation of new modes of chattel slavery: chain gangs, sharecropping, tenant farming, convict leasing, and prison farms. One manifestation of the “Tragic Mulatto” held that the offspring of an interracial relationship found her- (or him-) self torn between two biological inheritances.

The legacy of “separate but equal,” from the infamous 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, survived in the white popular imagination and encouraged seven Black literary stereotypes in American literature. In prose that was both analytic and satiric, Brown challenged the illogic of these misrepresentations. For the 1920s and 1930s, Brown’s critical act was innovative. He was the first literary historian to explore the social necessity that formed the basis for these stereotypes. The “Brute Negro,” for example, resulted from the post-Reconstruction imperative used to justify the recreation of new modes of chattel slavery: chain gangs, sharecropping, tenant farming, convict leasing, and prison farms. One manifestation of the “Tragic Mulatto” held that the offspring of an interracial relationship found her- (or him-) self torn between two biological inheritances.

The resulting tension between the “intellectual strivings” from the character’s white inheritance and the character’s “baser, emotional urges” from his/her Black parent ends tragically because the character is unable to reconcile these conflicting impulses. In late nineteenth century literature and early twentieth century film, the mulatto character served to warn whites of the “imminent danger” in miscegenation. Brown’s reasonable refutation of these and the other stereotypes sought to develop a more intellectually-aware and culturally-competent audience. Brown dramatically asserts the prospects of personal transformation, which, in turn, forces individuals into a confrontation with their past and present.

Shrouded by a world of uncertainty and confusion, we can look to Sterling A. Brown’s precept and example for an antidote. Fundamentally, Brown was a humanist. The Southern road upon which he embarked was a journey not just into the heart of a racial past but into the very humanity of a people. There, he found the love June Jordan later writes about. His travels enable us to see that an enlightened citizenry must be capable of having a conversation about differences. A conversation, simply, is a two-way communication. It is not about power; it is not about shouting louder than the other person; it is not about behaving irrationally or badly. A conversation begins and ends with mutual respect. It means more than listening to someone; it means hearing that person.

The metaphor of “hearing” is quite appropriate, given our current political environment. If Brown were here today, he would see the persistence of his “Brute Negro” stereotype in the loss of young Black lives at the hands of white policemen. Racial profiling exists under the pretext of crime prevention; in actual practice, however, it defines a group on the basis of a few generalized traits. It seeks to control people regardless of whether they are actually engaged in criminal activities.

Similarly, Brown would see the mischaracterization of mixed race people—his tragic mulatto—survive in more complicated iterations today. The old interracial binary of Blacks and whites is problematized by new, infinite combinations of ethnicities. Equating “biological” background with “intellectual ability” is even less tenable now than when Brown first debunked the stereotype. The traditional notations on such documents as the census form or driver’s license are incapable of accommodating the choices mixed race people use to describe themselves.

Art, for Sterling A. Brown, was a corrective, but not in the pejorative sense of expounding doctrinaire ideas. Art expands the mind and transforms the world. To commemorate Sterling A. Brown, we pause to remember all that he bequeathed us. We thank him for leaving us an enduring legacy demonstrating the potential of art to improve ourselves and the world we all inhabit.

(*This post was written to honor Sterling A. Brown on what would have been his 116th birthday. Dr. Tidwell wishes to thank his colleagues Drs. Maryemma Graham and Clarence Lang for their thoughtful commentary.)