This content is being reviewed in light of recent changes to federal guidance.

Ann B. Garvin: Educator, Advocate for Women, Children and Youth

Categories: HBW

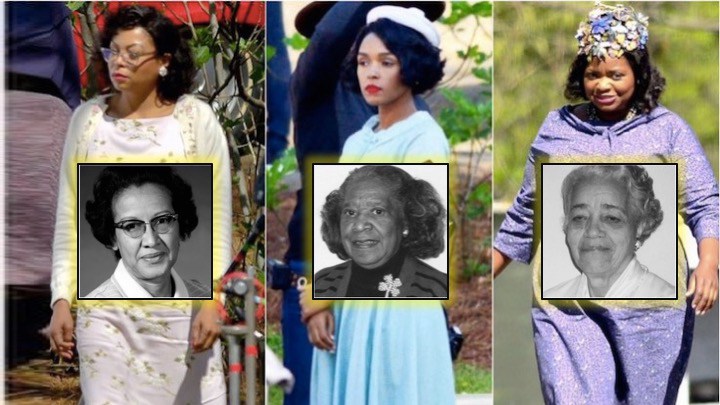

Continuing our celebration of “hidden figures” in Kansas, Dr. Maryemma Graham sat down with Mrs. Ann B. Garvin to discuss her lifelong commitment to education and advocacy for women, children and youth.

Mrs. Ann B. Garvin lives in the home her late husband built for her, in a somewhat secluded area of southwest Topeka. It’s hard to catch up with her, for although retired, she remains an active traveler, deeply involved in her church and community. She thinks a lot about her career as unintentional; she believed she was just doing what was “automatic.” When she attended a book talk on Hidden Figures at the Topeka Public Library earlier this year, she realized she had a story to tell and shared it with the audience that day. I wanted to know more, and she granted me an interviewed on March 17.

In 1958, Mrs. Ann B. Garvin became the first African American teacher at Topeka High School, in the very city that put Kansas on the national map in the battle over school desegregation just a few years earlier. Debates over the momentous Brown decision had hardly died down when Garvin joined the faculty at the city’s only high school. Topeka had made very little progress toward integration, not only in the schools but also in public facilities generally. Garvin was not a native Kansan, but had moved to Topeka as a newlywed to join her husband, who had already begun his career as a psychiatric social worker. In the early 1950s, Mr. Garvin had taken the bold step of introducing himself to Dr. Carl Meninger, who invited him to Topeka move. Garvin and her husband had met as students at Kentucky State College, an HBCU, and mapped out their future lives as professionals.

In 1958, Mrs. Ann B. Garvin became the first African American teacher at Topeka High School, in the very city that put Kansas on the national map in the battle over school desegregation just a few years earlier. Debates over the momentous Brown decision had hardly died down when Garvin joined the faculty at the city’s only high school. Topeka had made very little progress toward integration, not only in the schools but also in public facilities generally. Garvin was not a native Kansan, but had moved to Topeka as a newlywed to join her husband, who had already begun his career as a psychiatric social worker. In the early 1950s, Mr. Garvin had taken the bold step of introducing himself to Dr. Carl Meninger, who invited him to Topeka move. Garvin and her husband had met as students at Kentucky State College, an HBCU, and mapped out their future lives as professionals.

Growing up in Kentucky during the era of segregation, Mrs. Garvin does not represent a deficit model in her personal or educational background. Her grandparents and parents, uncles and aunts had all been educated at HBCUs. Her grandfather had taught at Hampton and she says there was no question that she would not only go to college, but also get an advanced degree. While the laws may have prevented her admission into the graduate school at the University of Kentucky, she took courses there and completed her Master’s Degree at Fisk before moving to Topeka.

Growing up in Kentucky during the era of segregation, Mrs. Garvin does not represent a deficit model in her personal or educational background. Her grandparents and parents, uncles and aunts had all been educated at HBCUs. Her grandfather had taught at Hampton and she says there was no question that she would not only go to college, but also get an advanced degree. While the laws may have prevented her admission into the graduate school at the University of Kentucky, she took courses there and completed her Master’s Degree at Fisk before moving to Topeka.

For several years, Garvin remained the only African American teacher at Topeka High. During her nineteen years in the school system, followed by employment with Shawnee County as a Court Appointed Special Advocate for Abused and Neglected Children (CASA) Garvin taught, mentored, and advocated for children and youth. The former chair of Topeka Day Care, she held key leadership roles in women’s organizations, some at the national level, serving as President of Women in Community Service, and some at the state level, where she is a former President of Kansas State Women’s Political Caucus.

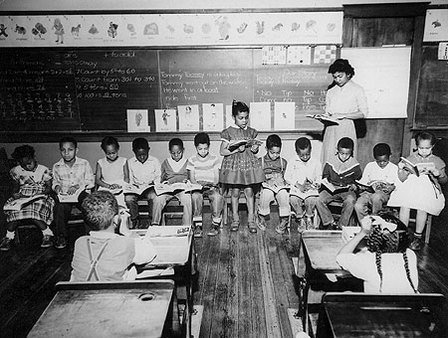

Although she joined the school system with an advanced degree, she was not allowed to teach the advanced classes, but Mrs. Garvin refused the box she was put in. Her students excelled because of her unique methods of instruction and her belief that education would and could make their lives better. In fact, when students in her “regular” classes began talking to their peers in the “advanced” classes, they were surprised to discover they were indeed receiving advanced instruction. To her, math provided invaluable skills. No student would leave her class without them. She advised her students to write to her with their concerns, she communicated directly with their parents, and she relied upon both individual and group instruction in her teaching. She integrated culture and history into the learning process, students didn’t see what they were learning as foreign. Nor did they find it especially difficult, despite Garvin’s reputation as a demanding teacher. She routinely began teaching math with the goal of understanding some basics: how to do a budget, buy a car, and read a road map. These assignments would last over a period of time as students used true facts for their calculations. She taught word problems by adapting from what she had learned in English: breaking down the whole into separate parts, similar to the way one diagrams a sentence.

Ann Garvin clearly had her own book of rules. She always believed that as an educator, she was “teaching for mastery and teaching for life,” not teaching for the test. As to the idea and—a current perception—that African American youth have difficulty with abstract thinking and are less likely to excel in math, she says, “That’s bull!”

Ann Garvin clearly had her own book of rules. She always believed that as an educator, she was “teaching for mastery and teaching for life,” not teaching for the test. As to the idea and—a current perception—that African American youth have difficulty with abstract thinking and are less likely to excel in math, she says, “That’s bull!”

So how did Mrs. Garvin operate her classroom? She was quite explicit in our March interview.

You have to teach mathematics as a mental and practical process . . . and incentivize the classroom by making it competitive without affecting student’s grades.

I would sometimes give the test that were not intended to produce answers, but their understanding of how to find the answer. I also gave them drills to provide more mental practice, and since they could not use pencils, they became quite good. My students were eager to complete the week’s assignments early, so that we could do math games on Friday. They brought in their own games and were learning from each other. When I taught algebra or geometry and we began working on proofs, I made that competitive by reducing the number of steps required to get to the answer. We’d start at 10 steps and the student who got to the lowest number first would write on the board.

If learning was more important than getting the right answer, Garvin is equally clear on the impact of school integration.

I hate to say it, but white teachers and black teachers teach from their experience, but these experiences are different. So when a white teacher doesn’t know the culture, is teaching a majority class of black students, and the student is having difficulty, it leads to the assumption that the black student cannot learn.

[After school integration] white teachers didn’t have the necessary knowledge, and the black students they were teaching didn’t have the experience. The issue is not ignorance, it’s lack of knowledge. My education was entirely segregated until I reached graduate school, and my teachers never saw a separation between what we were learning and what our experiences had been. Black History was never relegated to a single week.

Garvin also suggested that today’s parents are intimidated by schools and public institutions generally, “because of what our history has been.” The lack of trust disrupts what should be a partnership. The result is that “no one’s got your back,” and Mrs. Garvin had to do that even more when she worked at CASA. “Our last hope may be the church since this is one place where people feel connected to one another. But I truly believe that those who know need to pass on and support those who don’t know.” The rightness of her belief has been proven time and time again as successful students come back to thank her, and as she watches the young women and mothers with whom she worked become outspoken public advocates of change.

Ann B. Garvin is one of Kansas’s many hidden figures.